Rays out of Sight – Art and Radiation, A Visual Chronology since 1945

Dates: July 25 – October 5, 2025

Venue: MOMENT Contemporary Art Center, Nara

Artists: Hiromi Tsuchida, Kenji Yanobe, Takashi Kuribayashi

Introduction

From July 25 to October 5, 2025, MOMENT Contemporary Art Center in Nara is hosting the group exhibition “Rays out of Sight – Art and Radiation, A Visual Chronology since 1945”, featuring Hiromi Tsuchida, Kenji Yanobe, and Takashi Kuribayashi.

From left: Director Sae Cardonel-Shimai, Hiromi Tsuchida, Kenji Yanobe, Takashi Kuribayashi

This year marks the 80th anniversary of the atomic bombings. In Japan, the only nation to have directly suffered nuclear attack, this exhibition attempts to trace how artists have confronted radiation—the “invisible light”—and how they have expressed it, through works by artists of different generations and with different motifs.

Hiromi Tsuchida

Hiromi Tsuchida, exhibition view

Tsuchida’s motif is Hiroshima. Yanobe’s motif is the Chernobyl nuclear accident. Kuribayashi’s motif is the Fukushima Daiichi disaster. Yet the “radiation” they faced—an invisible presence—and the visible realities of destruction and damage, together sharply delineate the 80-year rings of postwar history.

Opened in February 2025, MOMENT Contemporary Art Center occupies the ground floor of a building facing Sanjo-dori, the main thoroughfare running east-west through central Nara. In this exhibition, Tsuchida’s works are shown in the central space, Kuribayashi’s in the glass-fronted entrance area and along the right-hand wall, and Yanobe’s on the back wall behind the counter and on the rear wooden wall of the central hall.

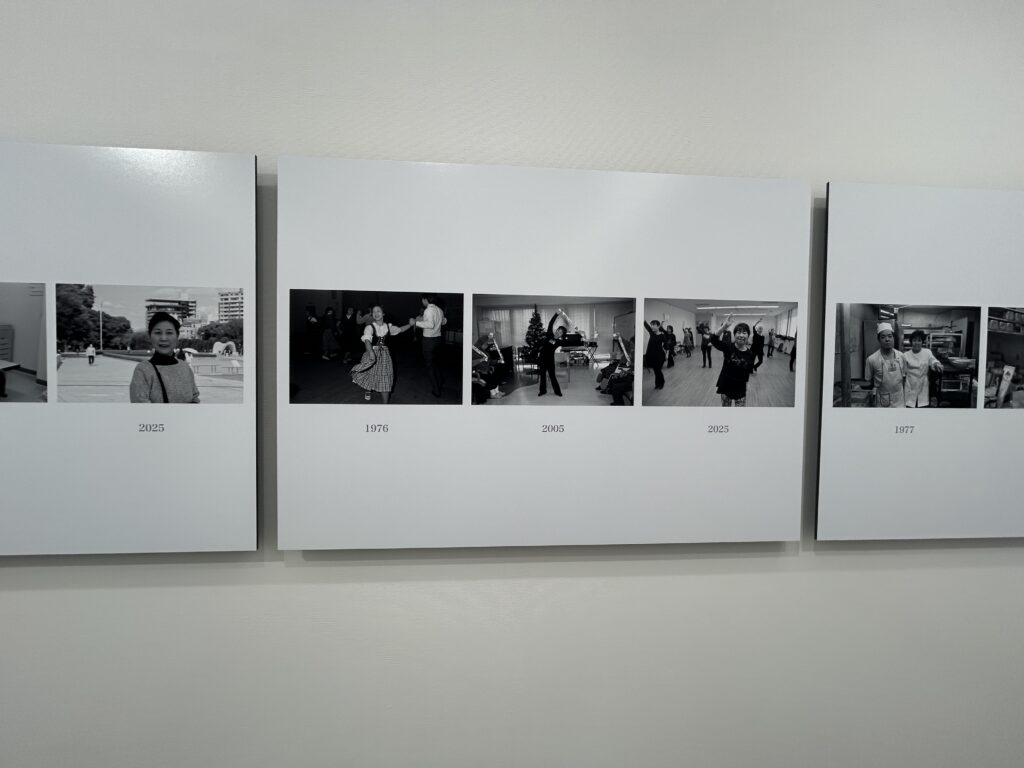

Hiromi Tsuchida, Hiroshima 1945–1979, series

Tsuchida presents his Hiroshima Trilogy. His first engagement with Hiroshima began in 1975. Based on Children of the Atomic Bomb – Testimonies of Boys and Girls of Hiroshima (edited by Arata Osada, Iwanami Shoten, 1951), which compiled writings by 186 children, Tsuchida photographed them over four years beginning in 1975, producing Hiroshima 1945–1979. Some had already died, others refused interviews. For this exhibition, portraits of three subjects taken in 2005, sixty years after the bombing, and again in 2025, eighty years later, were added.

Hiromi Tsuchida, Hiroshima Monuments series

The second series, Hiroshima Monuments, shifted from individuals to landscapes. By the mid-1970s, thirty years had already passed since the bombing, and the traces were increasingly difficult to detect. The Atomic Bomb Dome was one of the few visible remains, but radiation itself, of course, cannot be seen, nor can vanished things be photographed. In a sense, this was a quixotic undertaking. Using the Catalogue of Atomic Bomb Damage Materials, Vol. 1 (compiled by the Hiroshima Research Group on A-Bomb Damage Materials) as his guide, Tsuchida photographed one hundred surviving sites within the city, naming them “monuments.” He has since returned approximately every decade—1990–91, 2009–10, 2019–25—producing four series over forty years, now totaling forty-eight sites. Among those shown here is his photograph of the Atomic Bomb Dome with the Motoyasu River and Aioi Bridge in the foreground, taken from an elevated perspective that reveals the transformations of the surrounding cityscape over time.

The building, originally constructed as the Hiroshima Prefectural Products Exhibition Hall, became the “Atomic Bomb Dome.” Today it is internationally known and was inscribed as a World Heritage Site in 1996. But like the ruins of the Great East Japan Earthquake—many of which were demolished as painful reminders—the Dome too once faced possible demolition. It was preserved thanks to movements inspired by the words of Hiroko Kajiyama, who was exposed at age one and died of leukemia fifteen years later. She wrote in her diary: “Only that painful Industrial Promotion Hall will continue forever to appeal to future generations about the terrible atomic bomb.” The decision to preserve it was finally made in 1966. Kenzo Tange’s design for Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, which aligned the Peace Memorial Museum, cenotaph, and Dome in a powerful axis, also monumentalized the Dome. This was, in a sense, an act of symbolic pointing, the power of the gaze itself. Tsuchida, though not an architect, has done something similar through photography: by structuring the viewer’s gaze, he has monumentalized the ruins through what might be called an “architecture of vision.”

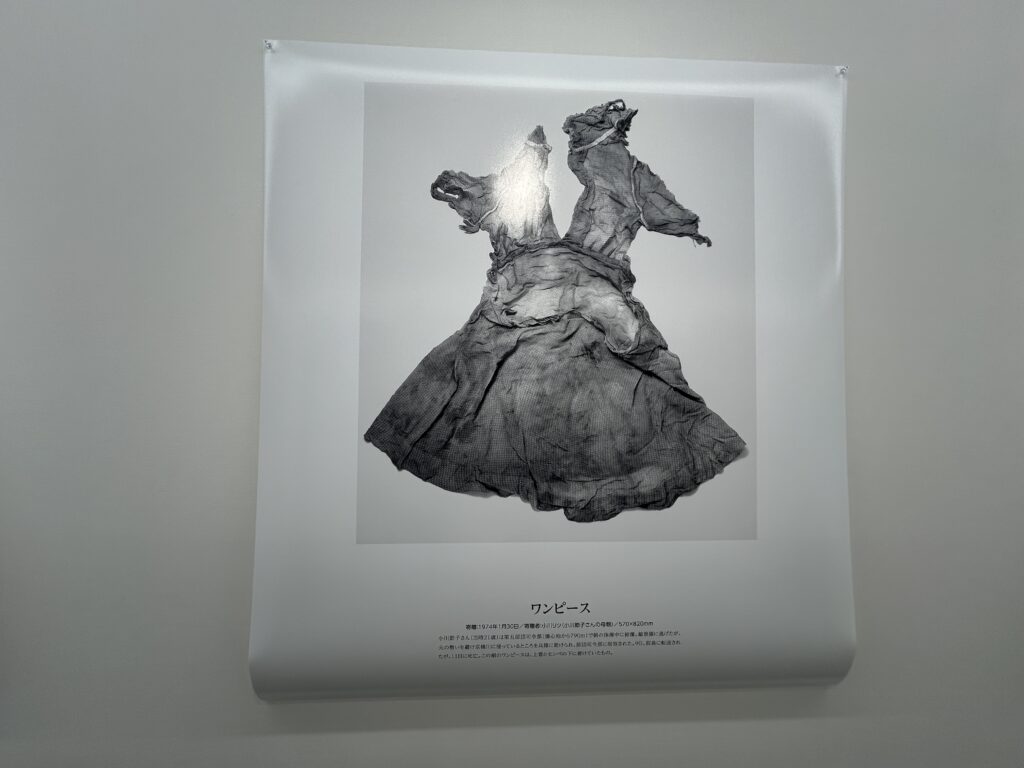

Hiromi Tsuchida, Hiroshima Collection series

The third series, Hiroshima Collection, documents objects. Tsuchida photographed bombed artifacts preserved in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum in stark monochrome, with text inserted to identify their provenance. Taken in 1981–82, 1995, 2018, and 2023–24, this project reveals that bomb artifacts continue to increase—evidence that Hiroshima’s suffering has not ended. Tsuchida has explained that he attempted to strip away personal expression, allowing the objects to speak through their provenance. In modernist terms, it might be preferable for photographs to stand alone. But without text, one cannot grasp the lived pain of those who owned or discovered these artifacts. The restrained monochrome photographs, paired with textual inscriptions, make audible the cries of destruction and grief.

Kenji Yanobe

Kenji Yanobe, Atom Suit Project: Nursery 4, Chernobyl (1997/2001)

Kenji Yanobe, by contrast, took a radically different approach. In 1997, he launched the Atom Suit Project, traveling to Chernobyl and other sites of nuclear disaster wearing his own radiation-sensitive suit. The exhibition features one work from this project: Atom Suit Project: Nursery 4, Chernobyl (1997/2001). The project, consisting of staged photographs with Yanobe himself as protagonist, represents the opposite pole from Tsuchida’s documentary method.

Yanobe grew up immersed in manga, anime, and tokusatsu (special effects films). His art has been recognized for importing the aesthetics of these postwar subcultures into contemporary art. Yet works like Astro Boy, Godzilla, and Space Battleship Yamato bear unmistakable shadows of war and the atomic bomb. In 1973, Ben Goto’s The Prophecies of Nostradamus intensified these anxieties. By the mid-1970s, Japanese children whispered that humanity would perish in July 1999 through nuclear war. For Yanobe’s generation, this was their first encounter with a sense of apocalypse, a fin-de-siècle worldview.

Yanobe debuted in 1990, just as the countdown to the “prophecy” began. In 1991, an accident occurred at the Mihama nuclear power plant, prompting him to create his first radiation-protection suit, the Yellow Suit, and to adopt “survival in contemporary society” as his theme.

In 1994, Yanobe moved to Berlin. The following year, the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake and the Tokyo subway sarin attack struck Japan. The earthquake was a replay of wartime aerial bombings, in a city Yanobe knew well. Yet from Berlin, he experienced it only through television, feeling no reality. The sarin attack seemed like a self-staged “Last Judgment,” echoing both Nostradamus and biblical apocalypse. The perpetrators were his contemporaries. Yanobe realized with anguish that the same destructive potential existed within himself. He began to fear that his works lacked reality, operating only in the protected fiction of the museum.

Determined to break out, he created the Atom Suit—a functional suit equipped with seven Geiger counters attached to vital points of the body. When radiation was detected, flashes of light and warning noises went off. It made invisible radiation both visible and palpable. Because perfect protection was impossible, he prioritized mobility, using raincoat material to shield against internal exposure.

In this sense, the Atom Suit inverted Astro Boy—a robot powered by atomic energy—into a fragile, survivalist gear. To realize his vision, Yanobe saved money for two years, then with a guide and photojournalist, obtained permission to enter Chernobyl’s 30 km exclusion zone. The work exhibited here, Atom Suit Project: Nursery 4, Chernobyl, is a lightbox photograph taken in a kindergarten in Pripyat, the town built for Chernobyl workers. Pripyat, constructed in 1970, was evacuated without explanation after the accident, becoming a ghost town. Its now-famous yellow Ferris wheel in the amusement park was scheduled to open on May 1, 1986—May Day—but never did, remaining a ruin.

In the photograph, Yanobe, clad in the Atom Suit, lifts a decayed doll in an abandoned apartment-turned-nursery. Later, when re-examining the negatives in 2001, he noticed a mural of the sun painted on the back wall. He experienced this as a revelation—a symbol of hope—that marked a turning point in his work, where the sun became a central motif of regeneration.

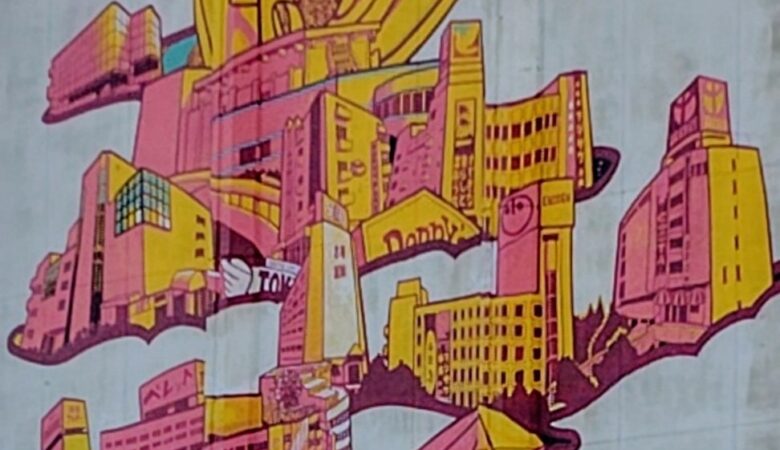

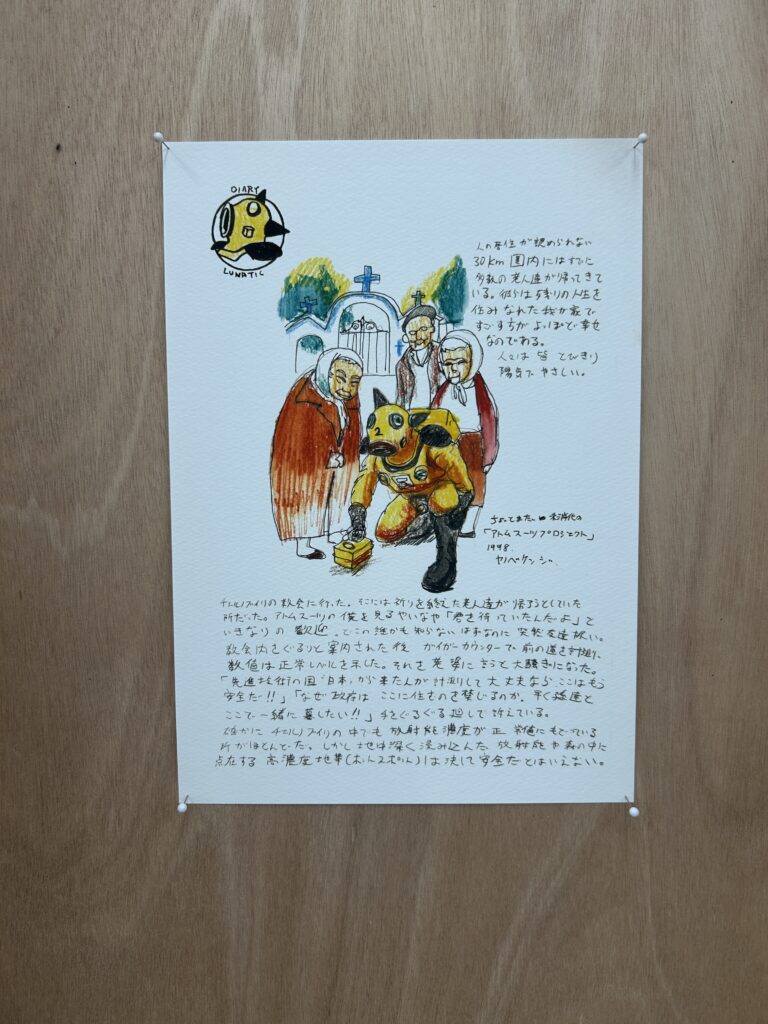

Kenji Yanobe, Atom Suit Project: Drawings series (1998)

On the opposite wall, his Atom Suit Project: Drawings (1998) are displayed. Rendered like diary entries, they recount his inner reflections in Chernobyl: how the ruins echoed the abandoned sites of Expo ’70 in Osaka, which had inspired his childhood imagination; how he met returning villagers in the forbidden zone, some hostile, some welcoming; how he played with the three-year-old child of a divorced woman who had come back. Today, many understand the severe danger of raising a child in radiation hotspots. Yanobe regretted involving villagers in his project, and has continued to ponder how to atone for and sublimate this experience in his artistic practice.

Yet nearly thirty years have now passed since his Chernobyl journey. Large swathes of Chernobyl are battlefields again. Yanobe’s works have become testimonies and monuments, historical witnesses to their time. That is the larger meaning of art as expression. It also ironically fulfilled his intent: he wanted the Atom Suit not as a character but as a transcendent perspective from which to view the situation.

Takashi Kuribayashi

Takashi Kuribayashi, foreground: Genki-ro No. 9, Nara (2025); background: Genki-ro No. 1, Nizayama Forest Art Museum video (2019–2020)

Takashi Kuribayashi, born in Nagasaki, creates installations, drawings, and videos exploring the artificial and natural boundaries separating humans from nature and land. Based between Jogjakarta, Indonesia and Japan, he works internationally. Having moved to Germany early after the Cold War, he became active globally alongside artists such as Yoshitomo Nara and Shiro Matsui, who also went to Germany in the 1990s.

Even before the Great East Japan Earthquake, Kuribayashi was concerned with energy and the human–nature relationship. After Fukushima, he repeatedly visited the contaminated region, doing volunteer work while creating art. He discovered that although he thought he was giving support, he was in fact receiving vitality from the people. On the tenth anniversary of the disaster, he created Genki-ro, a steam sauna shaped like a nuclear reactor, exhibited at the Nizayama Forest Art Museum in Nyuzen, Toyama. Its form was modeled on the GE Mark I type reactors used at Fukushima.

Takashi Kuribayashi, exhibition view of drawings

Genki-ro was a temporary wooden installation, but also functional. Visitors could enter, inhale herbal steam, and drink tea. Inside, one could receive “energy.” Notably, ten years earlier, in 2010, Yanobe had exhibited at the same museum a prophetic installation in which radiation detected by a Geiger counter triggered the release of eight tons of water from a suspended vessel, creating a flood. After the disaster, this was recalled as “prophetic.” The link between Yanobe and Kuribayashi is thus profound.

Takashi Kuribayashi serving herbal tea

Kuribayashi’s Genki-ro has been installed in multiple sites, most prominently at Documenta 15 in Kassel (2022), directed by ruangrupa. There it achieved international acclaim. For this exhibition, Kuribayashi created a smaller Genki-ro Unit No. 9, Nara (2025), built during a short stay in Nara. Herbs are placed in a cylindrical kettle, heated with fire to prepare herbal tea. At the opening, Kuribayashi performed the boiling and serving of tea to visitors. He emphasizes using locally gathered herbs.

This inevitably recalls Rirkrit Tiravanija’s famed installations of serving Thai food. But Kuribayashi’s approach extends further: not confined within institutional frameworks, it emphasizes relationships with audience, nature, and energy, as well as the multisensory dimensions of smell, taste, and bodily immersion. Most significantly, his approach does not denounce or protest, but transforms negativity into affirmativity. This makes critical and radical aspects acceptable to many, and this is his remarkable contribution.

Conclusion

Though united by the theme of “radiation,” Tsuchida, Yanobe, and Kuribayashi differ in motifs and methods. Their works also reflect social and artistic transformations, eloquently speaking of the artist’s role in visualizing the invisible.

Exhibition director Sae Cardonel-Shimai has stated that, following the Nobel Peace Prize awarded in 2024 to Nihon Hidankyo (Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations), and with the 80th anniversary of the war’s end this year, she felt she must take action as the world once again moves toward war. In Japan, eighty years after defeat, social memory is fading. Yet around the globe, wars and conflicts intensify: Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the 2023 Israel–Palestine war, and others with no end in sight. The use of tactical nuclear weapons—far more powerful than Hiroshima’s—is increasingly considered. We may be living in the closest era to nuclear war since 1945.

The “gaze toward the invisible” offered by artists may seem powerless against geopolitics. Yet it is undeniable that only artists can reveal certain ways of seeing and feeling. How should humanity confront the “invisible energy” that determines its fate? The work of these three artists will continue forward. Conversely, once the “invisible energy” becomes visible, humanity’s fate may already be sealed. That is precisely why artists must persist in turning their gaze toward the invisible.