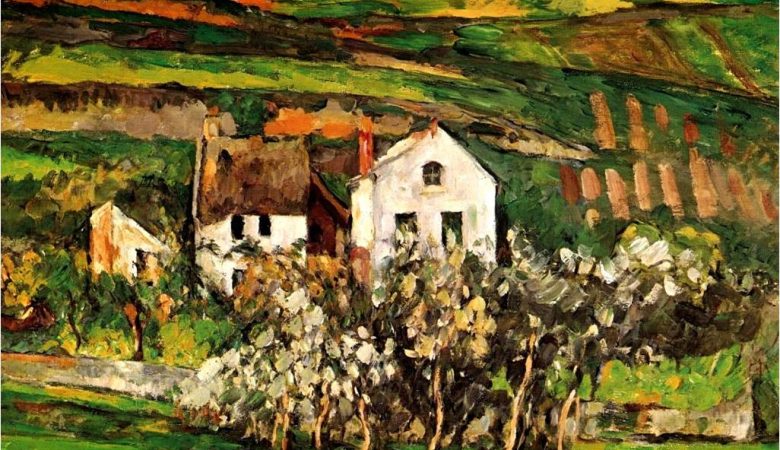

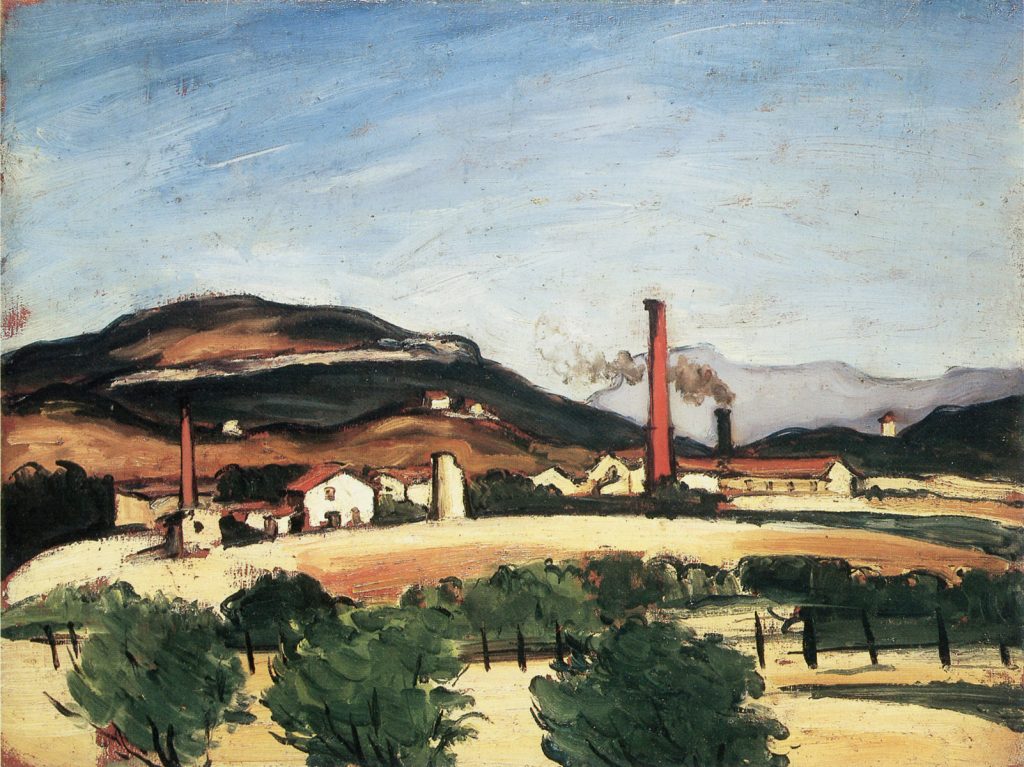

Fig. 25 Paul Cézanne House and Farm at Jas de Bouffan 1887

The Ferry at Bonnières (Fig. 15) painted by Paul Cézanne in 1866 topicalizes the railway, which was an iconic subject of “modernité (modernity)” at the time. After that, did he make any further depictions of the railway or its related subjects?

It was generally surmised that since Cézanne was an ardent lover of nature, he fled Paris that was undergoing rapid modernization and retreated to the pure nature of Aix-en-Provence, his hometown in the countryside.

Although this discourse might be factual to some extent, it certainly does not represent the essential Cézanne. An impartial research on his life and works will confirm that that Cézanne used the railway on a daily basis and painted many railway subjects in Aix-en-Provence.

Actually, during Cézanne’s lifetime, he traveled more than 20 times by railway between Aix and Paris. In Camille Pissarro’s letter to his son Lucien dated January 20, 1896, there is mention of Cézanne taking a train on the Paris-Aix line and of a telegram, which indicates that the telegraph was already a part of Cézanne’s daily life:

After numerous tokens of affection and southern warmth, Oller was confident that he could follow his friend Cézanne to Aix-en-Provence. They arranged to meet the next day on the P. L. M. train. ‘In the third class compartment,’ said Cézanne. So on the next day, Oller stood on the platform, straining his eyes and peering everywhere, but there was no sign of Cézanne! The trains departed. Nobody! Finally Oller said to himself: ‘He has gone, thinking I left already.’ He made a rapid decision and took the train. After he arrived in Lyon, a thief stole 500 francs from his purse at the hotel. Not knowing what to do, he sent a telegram to Cézanne. And Cézanne was, indeed, at home. He had left in a first class compartment![1]

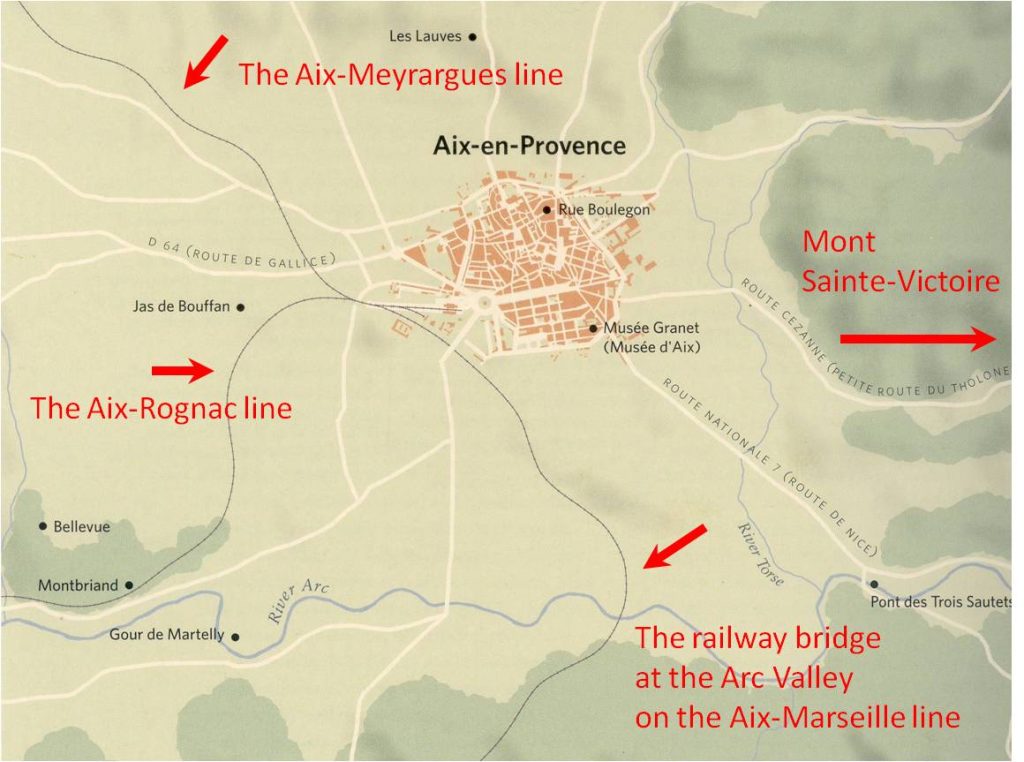

It was not common knowledge that Aix-en-Provence, which was Cézanne’s base during his entire lifetime, was actually a railway node (Fig. 26). Indeed, the railway station (Fig. 27, Fig. 28) near the main street of Aix connected three train lines. Chronologically, the railway company P. L. M. opened the train line from Aix to Rognac on October 10, 1856 (25 kilometers) (Fig. 29, Fig. 30), from Aix to Meyrargues on January 31, 1870 (26 kilometers), and from Aix to Marseille on October 15, 1877 (34 kilometers).[2]

Fig. 26 A map showing the vicinity of Aix-en-Provence

Fig. 27 Aix-en-Provence station

(Photographed by the author on August 26, 2006)

Fig. 28 A train at Aix-en-Provence station

(Photographed by the author on August 26, 2006)

Fig. 29 The Mont Sainte-Victoire seen on the Aix-Rognac line

(Photographed by the author on August 24, 2006)

Fig. 30 The Mont Sainte-Victoire seen on the Aix-Rognac line

(Filmed by the author on August 24, 2006)

It is worthwhile to note that Jas de Bouffan, Cézanne’s residence in Aix, was situated near the train lines from Aix to Rognac and to Meyrargues. Therefore, for about 40 years, whenever Cézanne worked in his atelier in this house, he must have been aware of steam locomotives roaring past his home (Fig. 25, Fig. 26).

In fact, if one turns right from the front gate of Jas de Bouffan, a short railway bridge on the Aix-Meyrargues line crosses above the roadway, and the Mont Saint-Victoire can be seen from that location (Fig. 31-Fig. 33). Cézanne must have often seen trains passing through this intersection with the mountain in the background.

Fig. 31

Fig. 32

Fig. 33

Fig. 31-33 The Mont Sainte-Victoire and the railway bridge on the Aix-Meyrargues line seen from the front gate of Jas de Bouffan

(Photographed by the author on August 23, 2006)

As a fact, Cézanne drew many railway subjects in Aix.

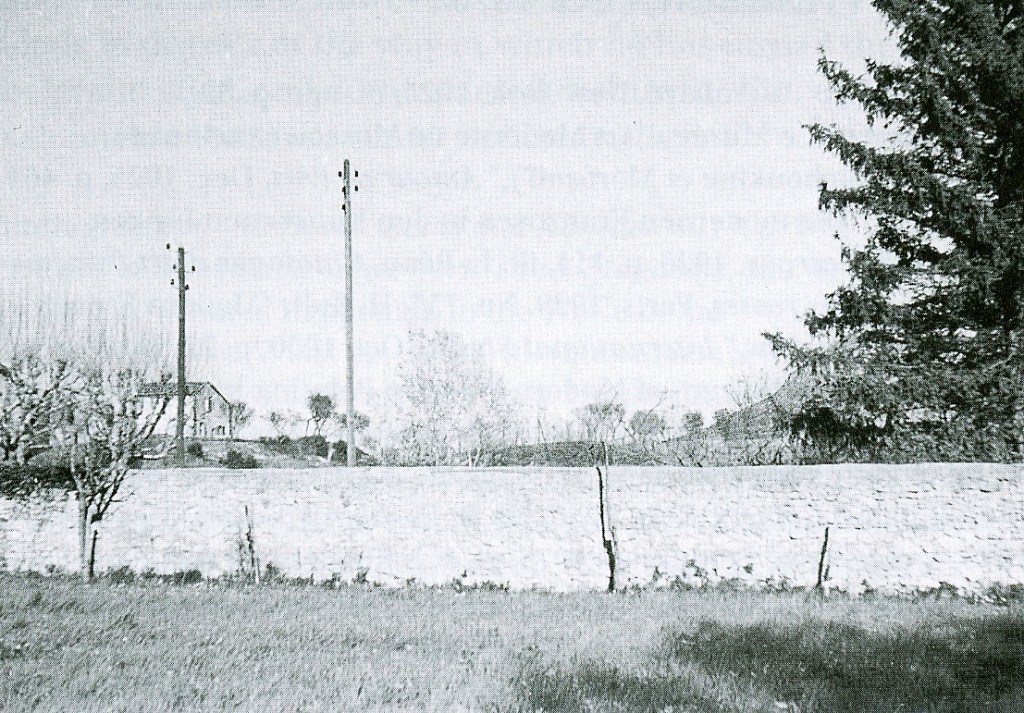

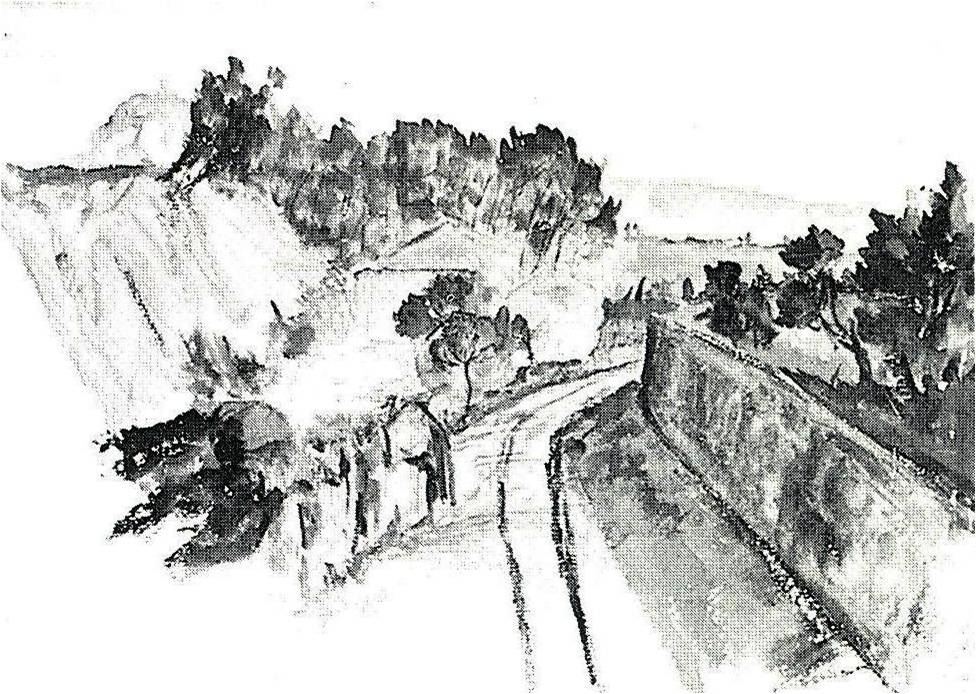

First, he sketched the railway cutting on the Aix-Rognac line which was visible from his garden at Jas de Bouffan about 100 meters away (Fig. 34) to create The Railway Cutting with the Mont Sainte-Victoire (c. 1870) (Fig. 35) in oils.

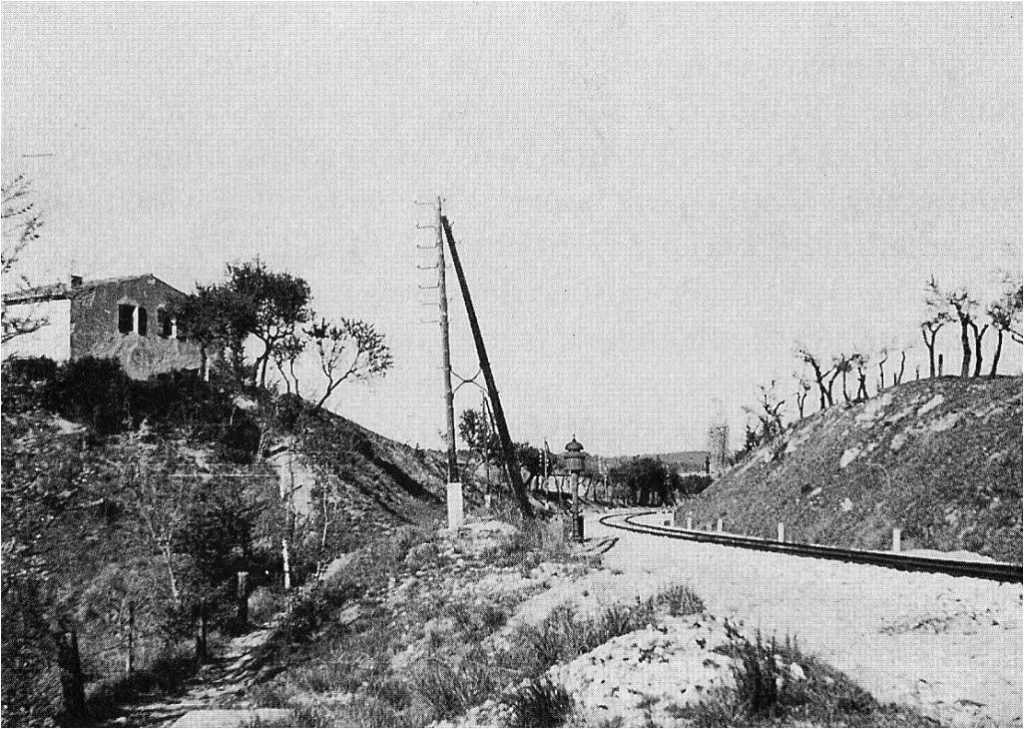

Second, in his preceding works, Cézanne not only drew the railway cutting but also the railway signal on the same line (Fig. 36, Fig. 37): The Railway Cutting (1867-1868) (Fig. 38) in an oil painting on board and The Railway Cutting (1867-1868) (Fig. 39) in a drawing.

Third, The Railway Cutting (1867-1870) (Fig. 40) depicts the railroad as well as the railway cutting in watercolor.

In these paintings, his enthusiasm was evident as he tried to topicalize the railway in his early years in Aix. He gradually refined his concept and focused on emphasizing the contrast between modernity (the railway) and pre-modernity (the mountain).

Fig. 34 The Mont Sainte-Victoire and the railway cutting seen from the garden of Jas de Bouffan

(Photographed by John Rewald in around 1935)

Fig. 35 Paul Cézanne The Railway Cutting with the Mont Sainte-Victoire c. 1870

Fig. 36 A railway cutting and a railway signal on the Aix-Rognac line

(Photographed by John Rewald in around 1935)

Fig. 37 A railway signal on the Aix-Rognac line

(Photographed by the author on August 23, 2006)

Fig. 38 Paul Cézanne The Railway Cutting 1867-1868

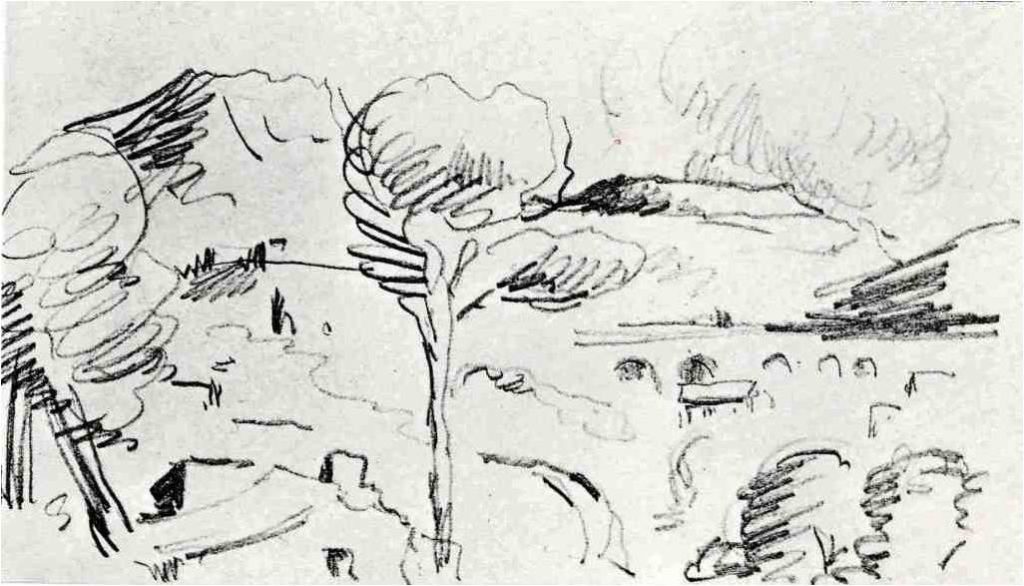

Fig. 39 Paul Cézanne The Railway Cutting 1867-1868

Fig. 40 Paul Cézanne The Railway Cutting 1867-1870

During that same period, Cézanne painted Factories at L’Estaque (1869) (Fig. 41). This watercolor on paper mounted on a board depicts the factories at L’Estaque, a neighboring town, and was used to decorate the vanity of Alexandrine Zola, Émile’s wife. Like the railway and the telegraph in The Ferry at Bonnières (Fig. 15), this factory subject was certainly topicalized for the sake of Cézanne’s friendship with art critic Zola, who praised modernity in art, much to the displeasure of the older generations. This painting of factories was deemed quite unsuitable for the decoration of a vanity and was not to Alexandrine’s liking.

After his first depiction of factories, Cézanne drew Factories near the Mont de Cengle (1869-70) (Fig. 42), in which smoke issues from the factories in front of the Mont de Cengle to the right of the Mont Sainte-Victoire. Cézanne drew these modern buildings as a subject of modernity in his oil paintings. More precisely, in this work, Cézanne expresses not only modernity but also the contrast between modernity (the factory) and pre-modernity (the mountain).

Fig. 41 Paul Cézanne Factories at L’Estaque 1869

Fig. 42 Paul Cézanne Factories near the Mont de Cengle 1869-1870

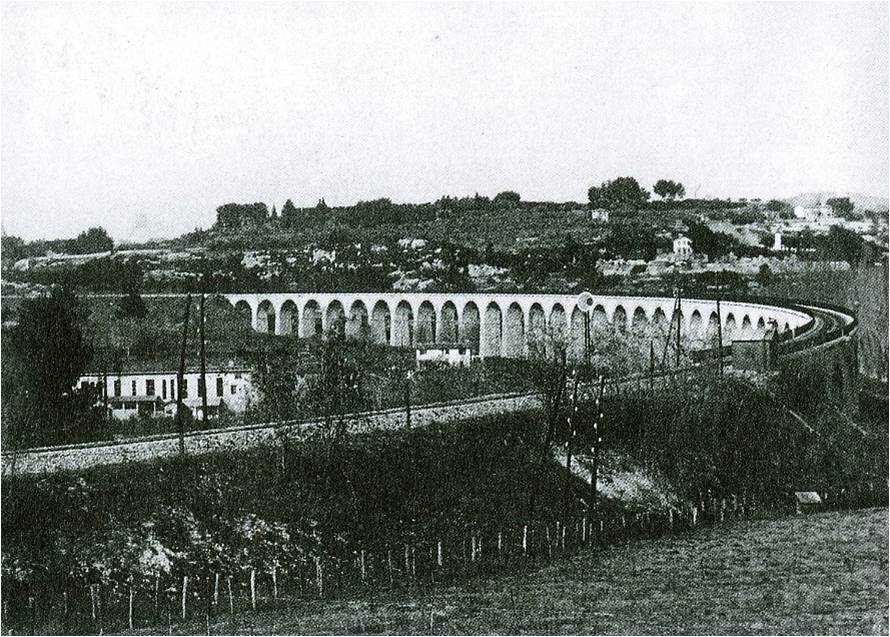

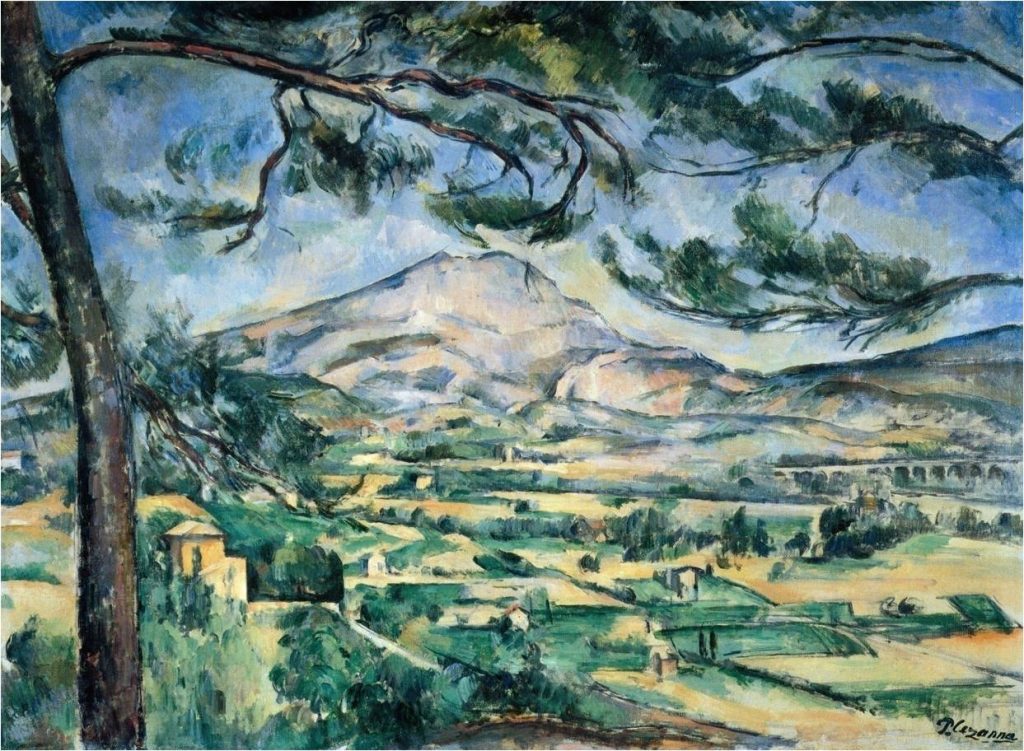

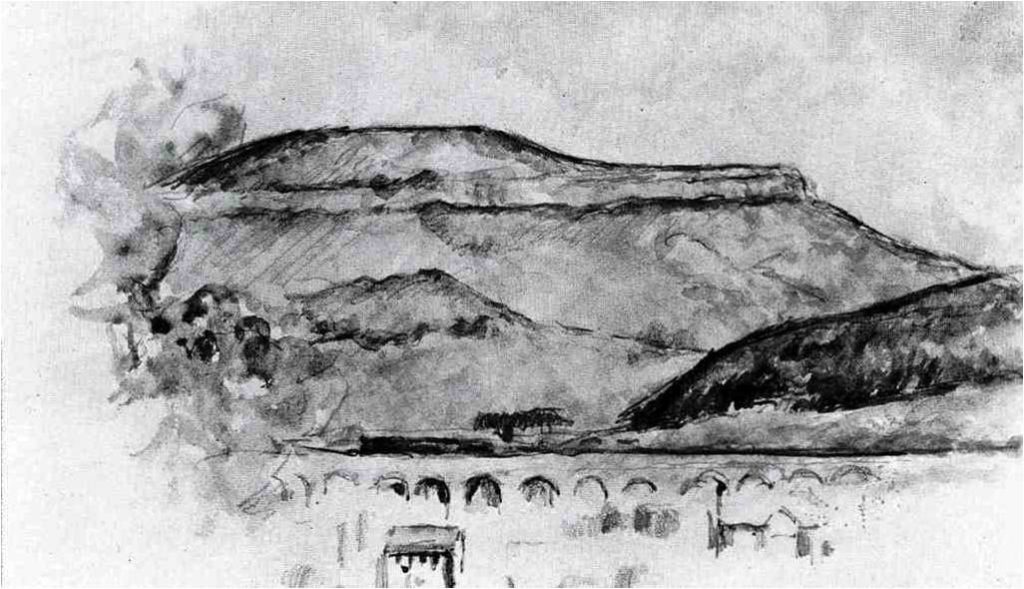

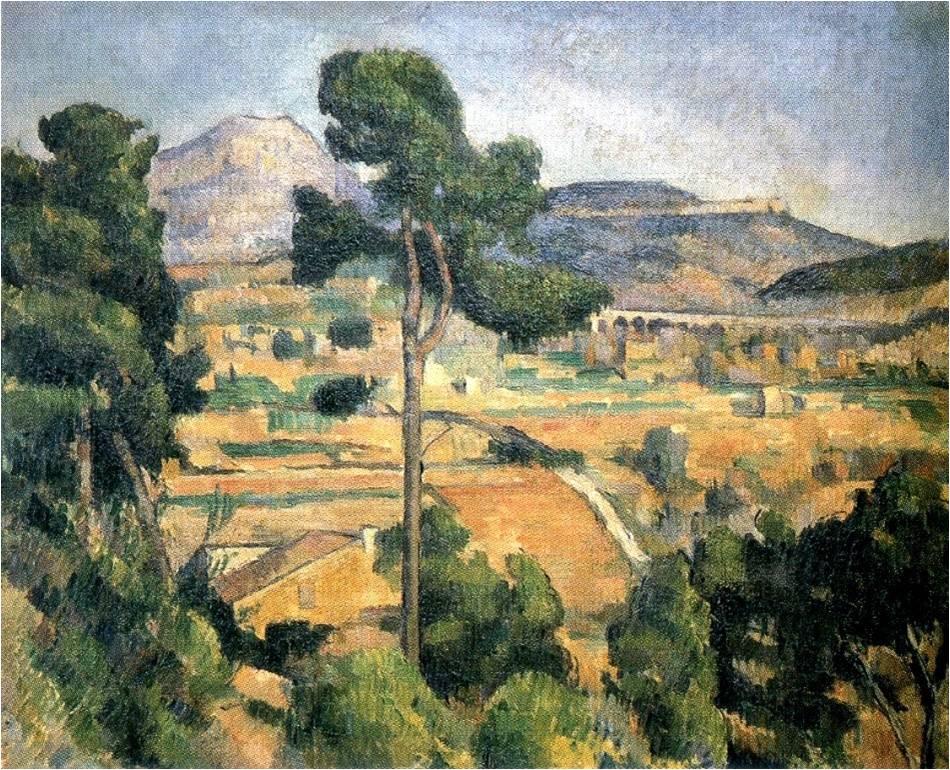

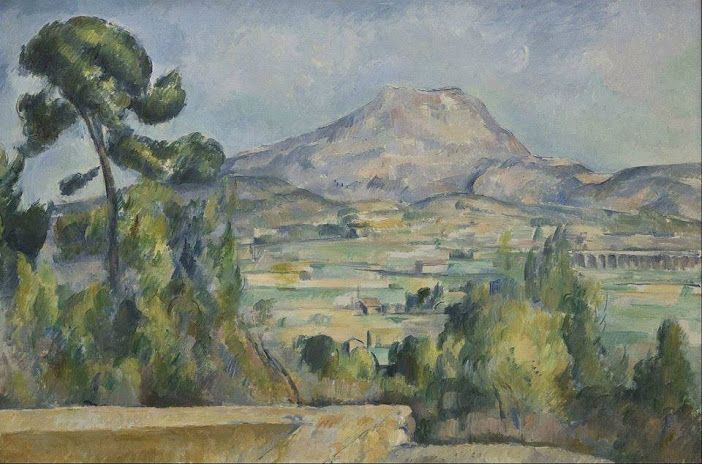

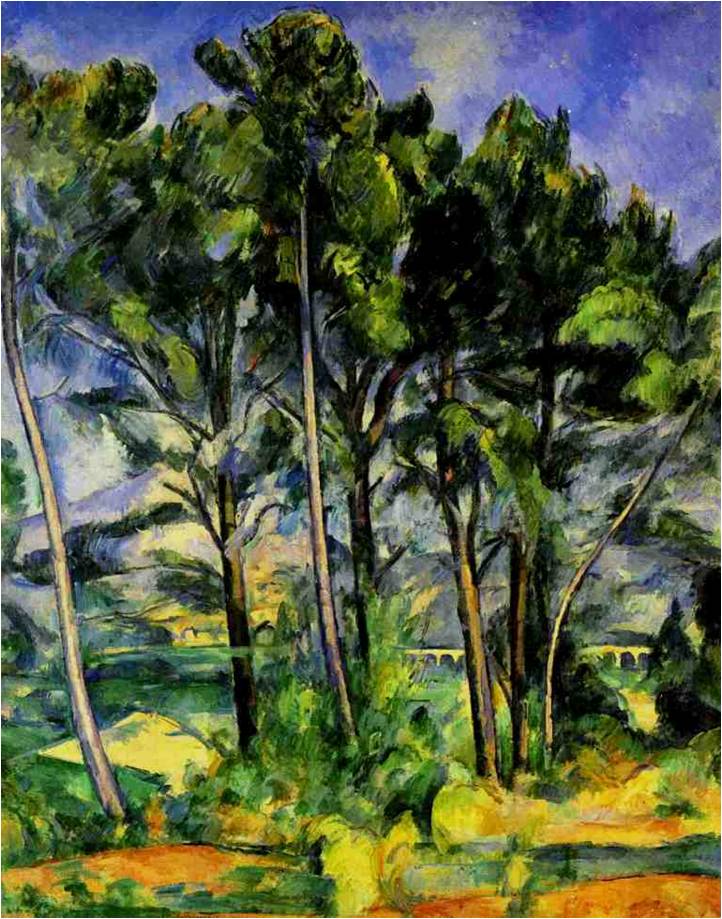

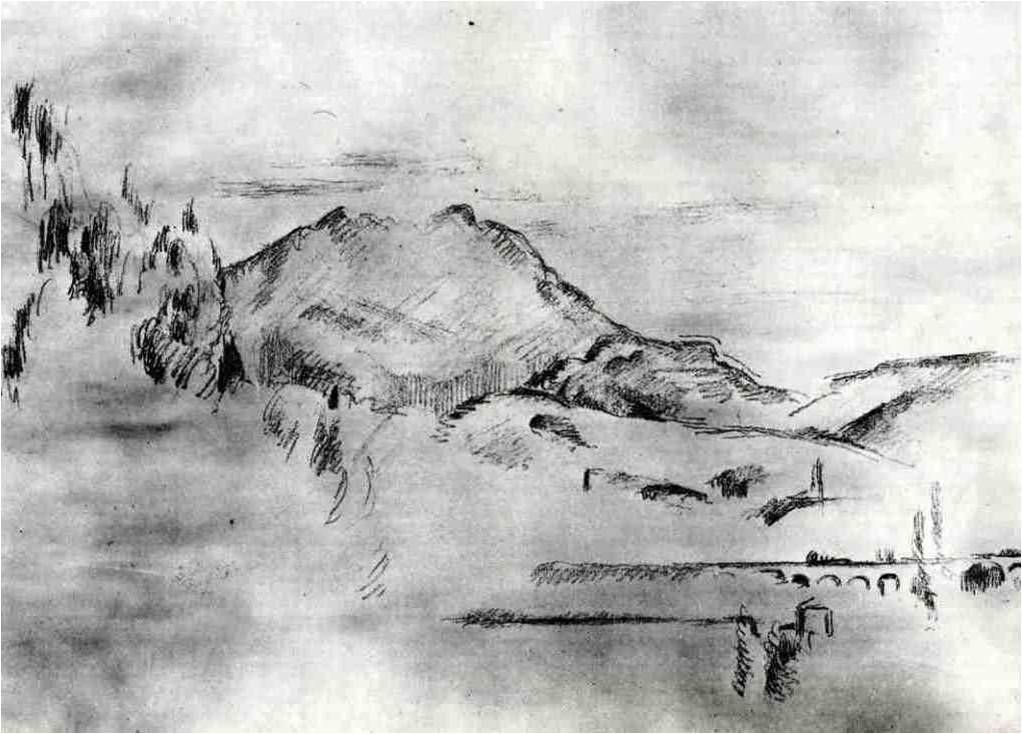

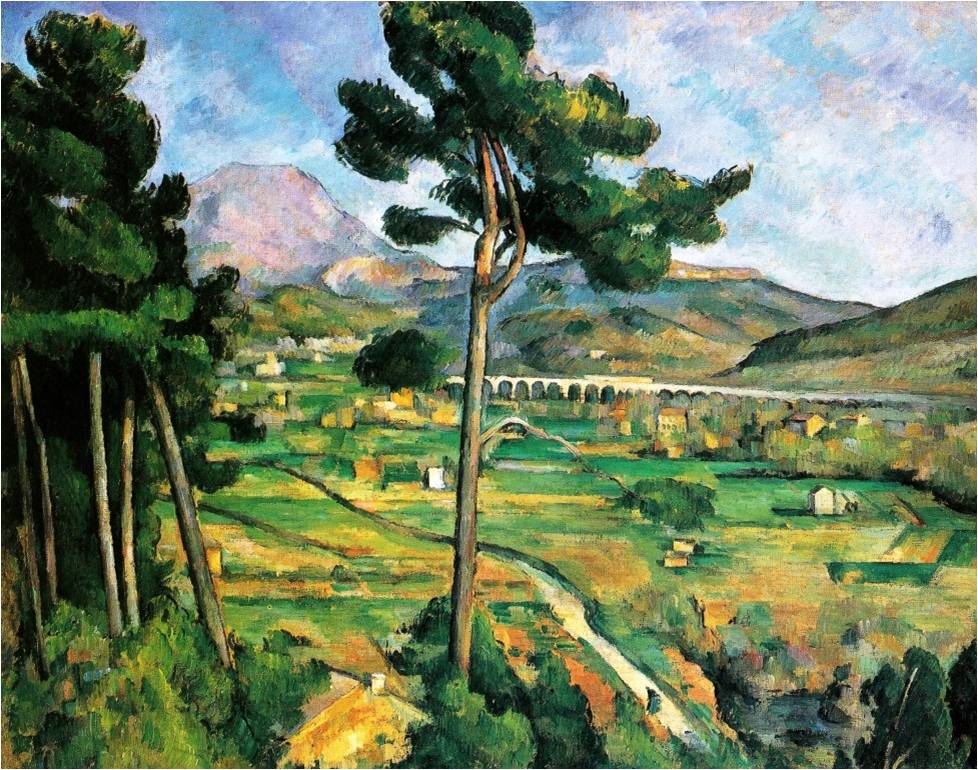

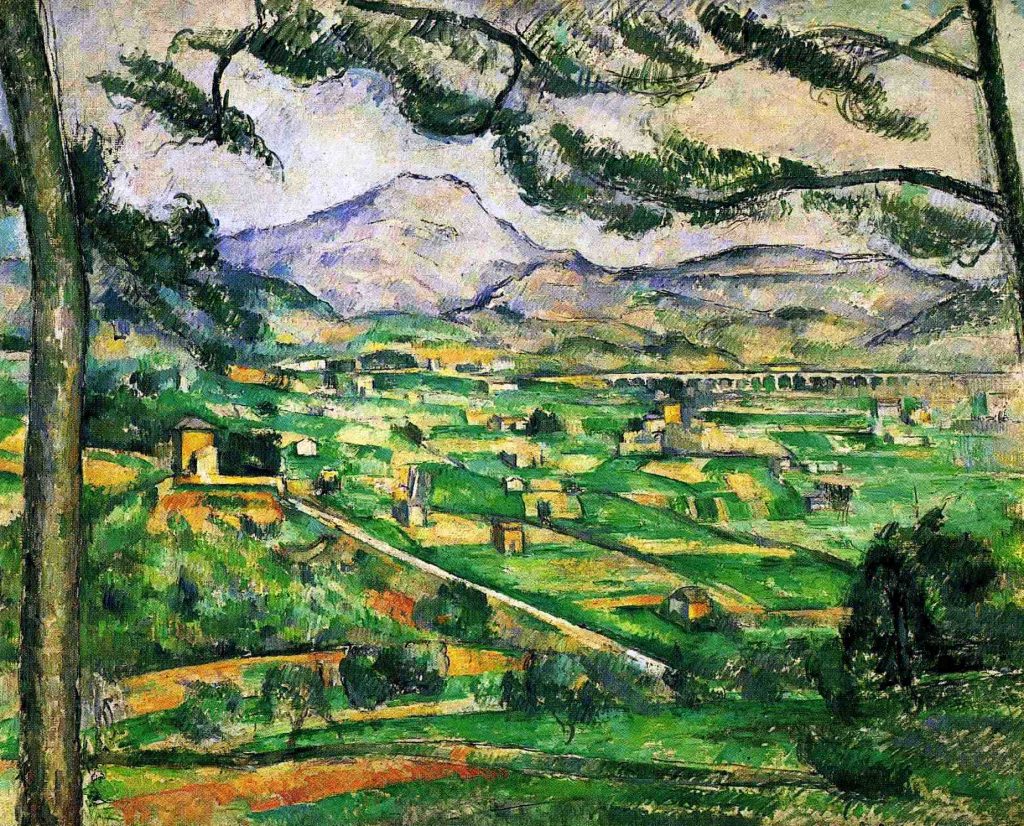

Moreover, Cézanne depicted the railway bridge on the Aix-Marseille line. He sketched the railway bridge which spanned the Arc River and the valley in a suburb of Aix (Fig. 43, Fig. 44), as is shown in The Mont Sainte-Victoire with Large Pine (c. 1887) (Fig. 2), Pine Tree in the Arc Valley (1883-1885) (Fig. 45), The Viaduct of the Arc Valley (1883-1885) (Fig. 46), The Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Montbriand (c. 1882) (Fig. 47), The Mont Sainte-Victoire (c. 1890) (Fig. 48), The Viaduct (c. 1890) (Fig. 49), The Mont Sainte-Victoire (1892-1895) (Fig. 50), The Mont Sainte-Victoire with Viaduct (1885-1887) (Fig. 51), The Mont Sainte-Victoire (1883-1886) (Fig. 52), The Mont Sainte-Victoire with Pine (1883-1886) (Fig. 53), and The Arc Valley (1885-1887) (Fig. 54).

A possible interpretation of The Viaduct of the Arc Valley (Fig. 46) is that the buildings in Factories near the Mont de Cengle (Fig. 42) have been replaced by the railway bridge as yet another modern subject in contrast with the pre-modern mountain.

Cézanne also painted a steam locomotive on the Aix-Marseille line; he depicted a train passing through the railway bridge at Arc valley (Fig. 55), as is shown in The Viaduct of the Arc Valley (Fig. 46), The Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Montbriand (1882-1885) (Fig. 56), The Mont Sainte-Victoire with Large Pine (1886-1887) (Fig. 57), and The Arc Valley (c. 1885) (Fig. 58).

In The Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Montbriand (Fig. 56), Cézanne drew a train running on the straight railway bridge and a parson negotiating the meandering road to Aix. Here, he expressed the contrast between modernity (the railway) and pre-modernity (the roadway).

In his letter to Émile Zola dated April 4, 1878, Cézanne wrote that he missed a train and had to take the very same meandering road shown in the painting to return to his home in Aix. He walked about 30 kilometers; the walking figure may reflect that singularly fatiguing experience:

I am going to try to go to Marseille, I escaped on Tuesday, a week ago, to go and see my little boy; he is better, and I was forced to walk back to Aix seeing that the train given in my railway guide was wrong, and I had to be home for dinner.—I was an hour late.[3]

Interestingly, the location where Cézanne sketched was above the railroad of the Aix-Rognac line (Fig. 59, Fig. 60). It was therefore highly probable that he often heard the roar of trains running underneath while he was working on these paintings.

Fig. 43 The railway bridge at the Arc valley around 1903

(Photographer unknown)

Fig. 44 The Mont Sainte-Victoire and the railway bridge at the Arc valley seen from Montbriand

(Photographed by the author on August 24, 2006)

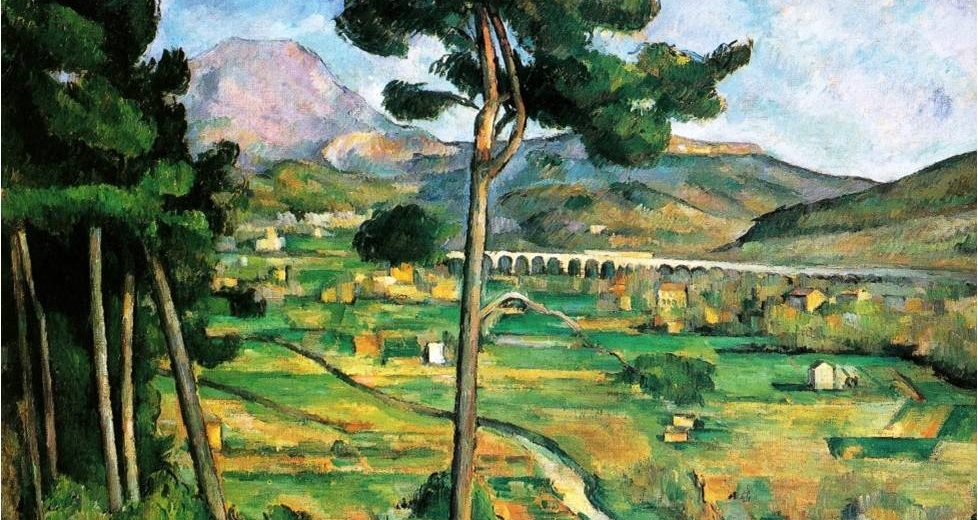

Fig. 2 Paul Cézanne The Mont Sainte-Victoire and Large Pine c. 1887

Fig. 45 Paul Cézanne Pine Tree in the Arc Valley 1883-1885

Fig. 46 Paul Cézanne The Viaduct of the Arc Valley 1883-1885

Fig. 47 Paul Cézanne The Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Montbriand c. 1882

Fig. 48 Paul Cézanne The Mont Sainte-Victoire c. 1890

Fig. 49 Paul Cézanne The Viaduct c. 1890

Fig. 50 Paul Cézanne The Mont Sainte-Victoire 1892-1895

Fig. 51 Paul Cézanne The Mont Sainte-Victoire with Viaduct 1885-1887

Fig. 52 Paul Cézanne The Mont Sainte-Victoire 1883-1886

Fig. 53 Paul Cézanne The Mont Sainte-Victoire with Pine 1883-1886

Fig. 54 Paul Cézanne The Arc valley 1885-1887

Fig. 55 The Mont Sainte-Victoire and the railway bridge at the Arc valley seen from Montbriand

(Photographed by the author on August 24, 2006)

Fig. 56 Paul Cézanne The Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Montbriand 1882-1885

Fig. 57 Paul Cézanne The Mont Sainte-Victoire with Large Pine 1886-1887

Fig. 58 Paul Cézanne The Arc Valley c. 1885

Fig. 59 The Mont Sainte-Victoire seen from Montbriand and the railroad of the Aix-Rognac line

(Photographed by the author on August 24, 2006)

Fig. 60 The Mont Sainte-Victoire seen from Montbriand and the railroad of the Aix-Rognac line

(Filmed by the author on August 25, 2006)

Cézanne enjoyed taking not only the steam train but also the electric train on the Aix-Marseille line. At the end of March 1905, Émile Bernard and Cézanne took the tram on this line which became electric on June 28, 1903[4]. Bernard described the event in his “Memories of Paul Cézanne” (1907):

As we were finishing our luncheon, he dismissed the carriage and announced that he was going to Marseilles to see ‘the rest of the family.’ We went off to the tram and, during two hours of torrid heat, we chatted cheerfully. His radiant mien, healthy appearance, and carefree attitude delighted me.[5]

It is certain that the steam train or even its electric version had already become a part of Cézanneʼs daily life, and, as a painter of modern life, he eagerly topicalized railway subjects such as the railway cutting, the railway signal, the railroad, the railway bridge, and the steam locomotive. Cézanne, a painter of modern life as well as a lover of nature, expressed with great enthusiasm the contrast between modernity and pre-modernnity.

[1] Camille Pissarro, Letters to his son Lucien, edited with the assistance of Lucien Pissarro by John Rewald, translated from the French manuscript by Lionel Abel, Boston: MFA Publications, 2002, p. 280. (cf. Camille Pissarro, Lettres à son fils Lucien, présentées avec l’assistance de Lucien Pissarro par John Rewald, Paris: Albin Michel, 1950, p.396.)

[2] See Wikia (http://trains.wikia.com/wiki/Aix-en-Provence) (Last retrieved on September 1, 2011)

[3] Paul Cezanne, Letters, edited by John Rewald, translated from the French by Marguerite Kay, New York: Da Capo Press, 1995, p. 158. (cf. Paul Cézanne, Correspondance, recueillie, annotée et préfacée par John Rewald, Paris: Bernard Grasset, 1937; nouvelle édition révisée et augmentée, Paris: Bernard Grasset, 1978, p. 164.)

[4] Marcel Provence, Le Cours Mirabeau: trois siecles d’histoire 1651-1951, Aix-en-Provence: Éditions du Bastidon Antonelle, 1976, p. 82.

[5] Émile Bernard, “Memories of Paul Cézanne” (1907), in Michael Doran (ed.), Conversations with Cézanne, translated by Julie Lawrence Cochran, Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: The University of California Press, 2001, p. 77. (Émile Bernard, “Souvenirs sur Paul Cézanne” (1907), in Conversations avec Cézanne, édition critique présentée par P. M. Doran, Paris: Macula, 1978, p. 77.)

Fig. 26 is quoted from exh. cat., Cézanne in Provence, Washington: National Gallery of Art, 2006.

Fig. 34 and Fig. 36 are quoted from John Rewald, The Paintings of Paul Cézanne: A Catalogue Raisonné, vol. I, New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1996.

Fig. 43 is quoted from John Rewald, Cezanne: A Biography, New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1986.