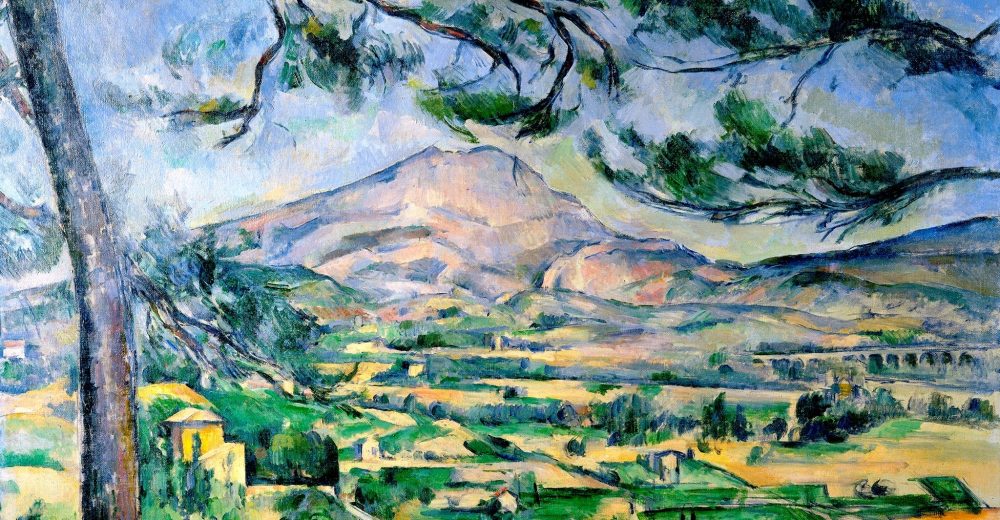

Fig. 1: Paul Cézanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire and Large Pine, c. 1887.

What did Paul Cézanne (1839–1906) seek to realize in his paintings?

Cézanne was the first painter in the world to internalize the transformation of visual perception brought about by the advent of the steam railway in the nineteenth century and to translate it into pictorial form. This crucial fact has remained overlooked for more than a century.

Indeed, the period in which Cézanne grew up was an era marked by the rapid development of the railway in France.

In 1837, a passenger railway was introduced in France, and Cézanne was born two years later. The railway network expanded rapidly during the 1840s, and most of the main lines connecting Paris with France’s major cities were built under the Second French Empire (1852–1870).

In 1861, at the age of twenty-two, Cézanne took his first long-distance train journey—from his hometown of Aix-en-Provence to Paris. Thereafter, he continued to travel frequently by steam train between Aix and Paris well into his later years.

Although Cézanne is generally known as a painter devoted to nature, he was also a painter of modern life.

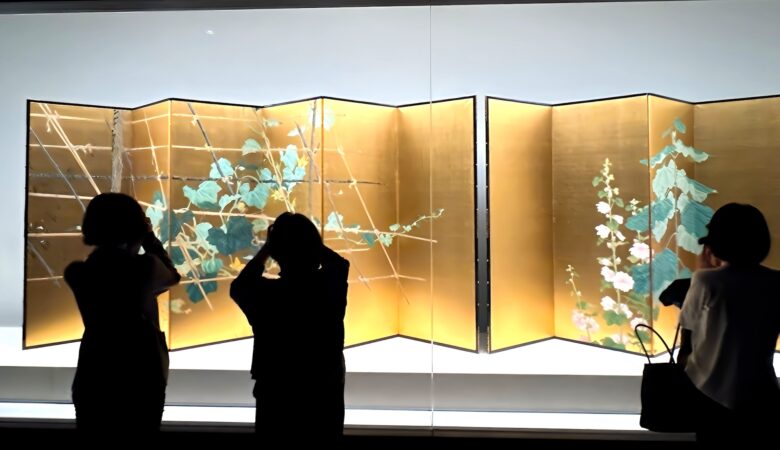

Fig. 2: Mont Sainte-Victoire and the railway bridge over the Arc Valley, seen from Montbriand.

(Photograph by the author, August 24, 2006.)

As long as movement depended on the horses’ strength and stamina, a horse-drawn carriage could average about 16 kilometers per hour. By contrast, steam locomotives in operation by 1845 could reach speeds of approximately 64 kilometers per hour—four times faster than a carriage.

Seen through the windows of a moving train, the swiftly passing scenery dissolved into fleeting, fragmentary images. This new mode of visual experience was consistently detested by the older generation, who were accustomed to a slower and more detailed appreciation of landscape.

The younger generation, however, soon learned to take pleasure in viewing the scenery through the windows of high-speed trains, and these transient images themselves came to be regarded as beautiful.

For example, Victor Hugo (1802–1885), in a letter to his wife dated August 22, 1837, enjoyed the passing scenery viewed from a moving train. He noted that, at such speed, the landscape appeared distorted, spotted and striped:

I am reconciled with the railway; it is decidedly very beautiful… The movement is magnificent, and it is necessary to experience it in order to feel so. The speed is extraordinary. The flowers by the side of the road are no longer flowers but flecks, or rather streaks, of red or white; there are no longer any points, everything becomes a streak; the grain fields are great shocks of yellow hair; fields of alfalfa, long green tresses; the towns, the steeples, and the trees perform a crazy mingling dance on the horizon.[1]

Similarly, Benjamin Gastineau (1823–1904), in La vie en chemin de fer (1861), admired the view from the train window, asserting that the steam railway gave rise to a beauty animated by motion:

Before the creation of the railroads, nature did not pulsate; it was a Sleeping Beauty… The heavens themselves appeared immutable. The railroad animated everything… The sky has become an active infinity, and nature a dynamic beauty. [2]

Furthermore, Jules Claretie (1840–1913), in Les Voyageurs de Paris (1865), celebrated the view from the train window, reflecting on the purification of form within the space of speed:

In a few hours, it [the railway] shows you all of France, and before your eyes it unrolls its infinite panorama, a vast succession of charming tableaux, of novel surprises. Of a landscape it shows you only the great outlines, being an artist versed in the ways of the masters. Don’t ask it for details, but for the living whole. [3]

Cézanne was one of the new generation who regarded this new mode of visual perception as beautiful, and he consequently developed new modes of pictorial expression influenced—whether consciously or unconsciously—by the kinetic experience of viewing the landscape in motion from the railway.

Indeed, in many of Cézanne’s paintings, the brushstrokes are rhythmically applied in a transverse direction, the ridgelines are horizontally emphasized, and the forms are rendered in broad masses, accompanied by a pronounced multiplicity of viewpoints (Figs. 1–2).

Fig. 3: Mont Sainte-Victoire, seen from the train while crossing the railway bridge over the Arc Valley.

(Photograph by the author, August 26, 2006.)

In a letter to his friend Émile Zola (1840–1902), written on April 14, 1878, Cézanne also praised the scenery viewed from the window of a moving train:

When I went to Marseille I was in the company of Monsieur Gibert. These people see correctly, but they have the eyes of Professors. Where the train passes close to Alexis’s country house, a stunning motif appears on the East side: Ste Victoire and the rocks that dominate Beaurecueil. I said: ‘What a beautiful motif’; he replied: ‘The lines are swaying too much.’ With regard to L’Assommoir, about which, by the way, he spoke to me first, he said some very sensible and laudatory things, but always from the point of view of the technique! [4]

Shortly after departing from Aix-en-Provence Station, the very landscape that Cézanne described comes into view through the window of the train bound for Marseille (Figs. 3–4). What Cézanne admired as “a beautiful motif” is, in fact, Mont Sainte-Victoire, which can be seen from the train as it crosses the railway bridge over the Arc Valley. The bridge itself is depicted at the center right of his painting (Fig. 1; Figs. 5–10).

Fig. 4: Mont Sainte-Victoire, seen from the train while crossing the railway bridge over the Arc Valley.

(Film by the author, August 26, 2006.)

Fig. 5: Mont Sainte-Victoire, seen from the railway bridge over the Arc Valley.

(Photograph by the author, August 22, 2006.)

Fig. 6: Railway bridge over the Arc Valley.

(Photograph by the author, August 22, 2006.)

Fig. 7: Railway bridge over the Arc Valley.

(Photograph by the author, August 22, 2006.)

Fig. 8: Railway bridge over the Arc Valley.

(Photograph by the author, August 22, 2006.)

Fig. 9: Railway bridge over the Arc Valley and Mont Sainte-Victoire.

(Film by the author, August 22, 2006.)

Fig. 10: Mont Sainte-Victoire seen beyond the railway bridge over the Arc Valley.

(Film by the author, August 25, 2006.)

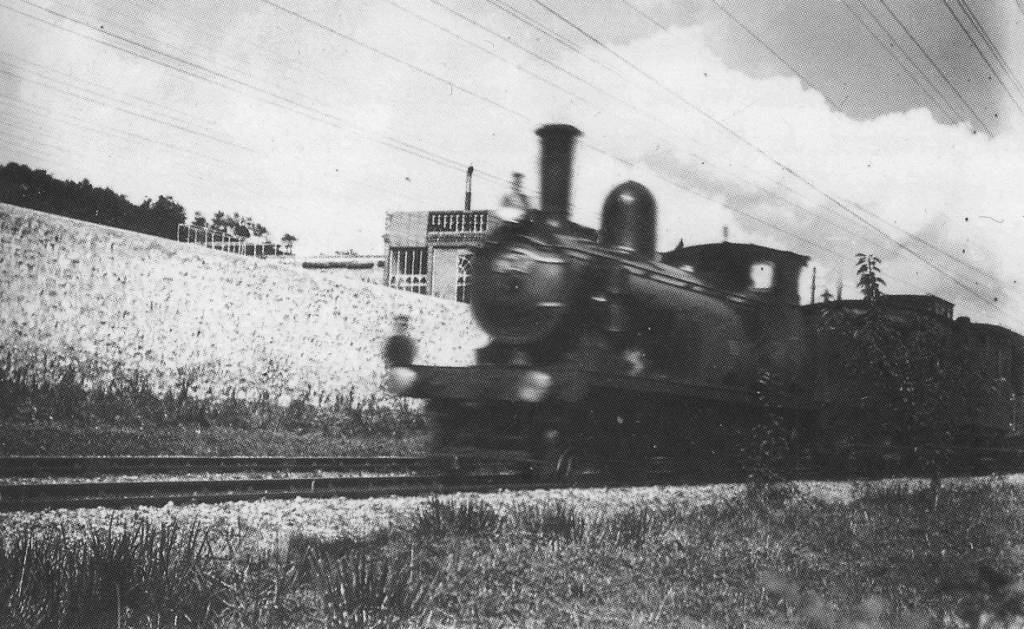

Fig. 11: A train in the late 19th century.

(Photograph by Émile Zola.)

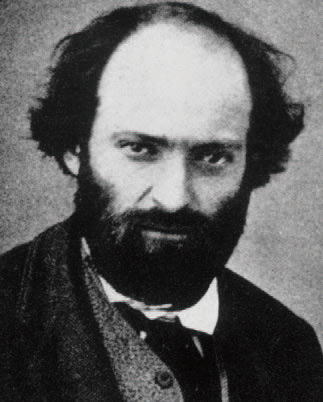

Fig. 12: Paul Cézanne at about 32 years old around 1871.

(Photographer unknown.)

It is noteworthy that Cézanne’s letter was written only six months after the opening of the railway line from Aix to Marseille—including the very bridge mentioned above—on October 15, 1877. Moreover, this letter represents the earliest known document in which the thirty-nine-year-old Cézanne referred to Mont Sainte-Victoire as a “motif,” and around 1878 he began his celebrated series of paintings devoted to the mountain.

It is highly probable that Cézanne’s Mont Sainte-Victoire paintings were inspired by his visual experience as the train crossed the railway bridge over the Arc Valley. Cézanne declared that the scenery viewed from a moving train was beautiful, and such aesthetic sensation is reflected in his paintings in one way or another.

Of course, Cézanne did not sketch the exact scenery visible through the window of a moving train. Even so, from the perspective of assimilating modern vision into artistic creativity, it is important to recognize that Cézanne painted natural landscapes by applying a new mode of perception—one inspired by railway travel and retained even after he stepped off the train.

It is a historical fact that the railway, which became widespread in the nineteenth century, brought about a revolution in visual experience in everyday life. Although the scenery seen from moving trains is scarcely noticed today, the images that were entirely new to Cézanne were realized in his art. In conclusion, Cézanne played a strikingly significant role as a recorder of the transformation of visual perception in human history (Figs. 11–12).

References

[1] Victor Hugo, Correspondance familiale et écrits intimes, tome II (1828-1839), Paris: Robert Laffont, 1991, p. 421. (Cited in Wolfgang Schivelbusch, The Railway Journey: The Industrialization of Time and Space in the 19th Century, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1986, p. 55.)

[2] Benjamin Gastineau, La Vie en chemin de fer, Paris: E. Dentu, 1861, p. 31. (Cited in Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, translated by Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin; prepared on the basis of the German volume edited by Rolf Tiedemann, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2002, p. 588.)

[3] Jules Claretie, Voyages d’un Parisien, Paris: A. Faure, 1865, p. 4. (Cited in Schivelbusch, The Railway Journey, p. 60.)

[4] Paul Cézanne, Correspondance, recueillie, annotée et préfacée par John Rewald, Paris: Bernard Grasset, 1937; nouvelle édition révisée et augmentée, Paris: Bernard Grasset, 1978, p. 165. (Paul Cézanne, Letters, edited by John Rewald, translated from the French by Marguerite Kay, New York: Da Capo Press, 1995, pp. 158-159.)

Fig. 11 is quoted from Émile Zola, Photograph, Eine Autobiographie in 480 Bildern, herausgegeben und zusammengestellt von François-Emile Zola und Massin, München: Schirmer/Mosel, 1979.

【Related Posts】

■ Tomoki Akimaru, Cézanne and the Railway (1) – (7): A Transformation of Vision in the 19th Century.

Cézanne and the Railway (1): A Hidden Origin of Modern Vision

Cézanne and the Railway (2): The Earliest Railway Painting Among French Impressionists

Cézanne and the Railway (3): His Railway Subject in Aix-en-Provence

Cézanne and the Railway (4): His Railway Subject in Médan, Pontoise, Gardanne, and L’Estaque

Cézanne and the Railway (5): A Stylistic Analysis of His Pictorial Form

Cézanne and the Railway (6): The Influence of the Machine on the Shift from Subject to Form

Cézanne and the Railway (7): What is the Realization of Sensations?

■ Tomoki Akimaru, Fauvism and the Automobile: A Transformation of Vision in the 20th Century.

● Marie Rauzy — A contemporary French painter descended from Paul Cézanne