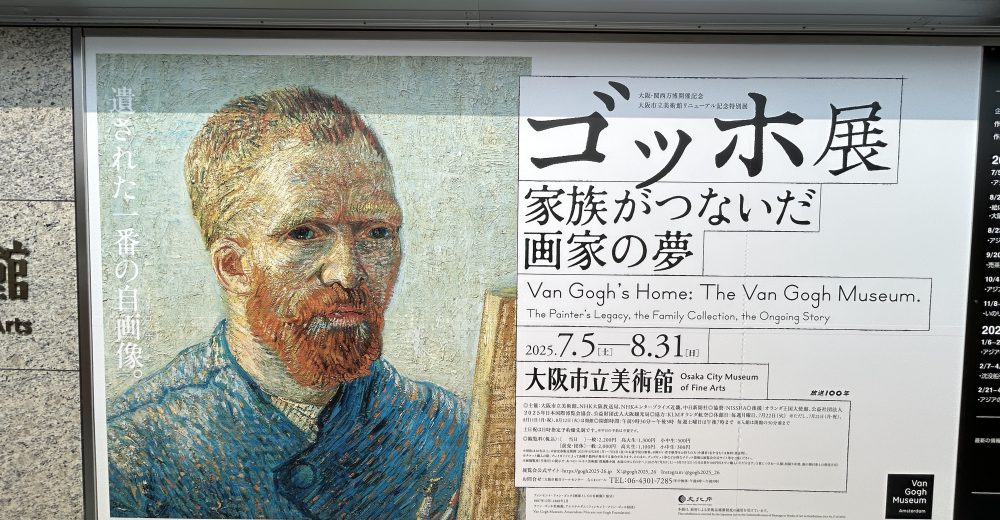

Van Gogh’s Home: The Van Gogh Museum. The Painter’s Legacy, the Family Collection, the Ongoing Story

Dates: July 5 (Sat) – August 31 (Sun), 2025

Venue: Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

From July 5 to August 31, 2025, the exhibition Van Gogh’s Home: The Van Gogh Museum. The Painter’s Legacy, the Family Collection, the Ongoing Story is being held at the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts. However, this exhibition differs in nature from conventional Van Gogh shows. Rather than focusing solely on Van Gogh himself, it highlights the role of the Van Gogh family, who made Van Gogh into the globally renowned painter he is today.

There is no artist in the world as famous as Van Gogh. Indeed, even when compared to iconic Impressionists such as Monet and Renoir, or to 20th-century representatives like Picasso and Matisse, their recognition is inferior to that of Van Gogh. Van Gogh is not only famous for his works but also for episodes that symbolize the enduring image of genius and madness in artists: cutting off his own ear, committing suicide, selling only one painting during his lifetime, and receiving constant financial support from his brother Theo.

However, if we examine the works alone, although they are certainly excellent, they inherit techniques from both Impressionism and Neo-Impressionism, and at the same time can be seen as works situated in a transitional period leading towards Fauvism and Expressionism. He was not a leader of any successive artistic movements, and thus there was a possibility he could have been forgotten. Why, then, has he not only avoided being forgotten but instead become so famous?

Johanna van Gogh-Bonger (left), wife of Theo; Theodorus van Gogh (right), Vincent’s brother; and Vincent Willem van Gogh (the child in the center), Theo and Johanna’s son.

This exhibition partially reveals that mystery. Van Gogh’s brother Theodorus (commonly called Theo) died only six months after Vincent’s death. After their deaths, Theo’s wife, Johanna van Gogh-Bonger (commonly called Jo), devoted her life to managing and promoting Vincent’s vast body of work. Jo might even be called a second Theo. While Theo supported Vincent spiritually and financially during his lifetime, after his death it was Jo who fulfilled the role of gaining societal recognition for him.

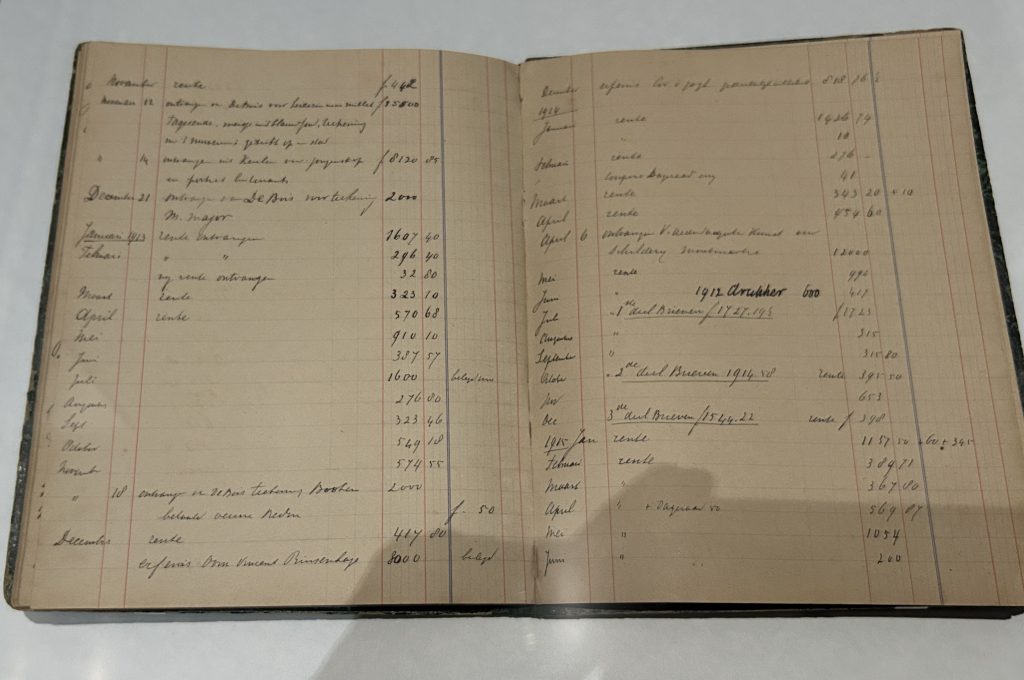

Jo actively cooperated in organizing Van Gogh exhibitions, compiled the letters between Van Gogh and Theo, and worked to raise Van Gogh’s reputation. She carefully sold works to museums around the world while preserving the others as family treasures. In this exhibition, Jo’s ledger recording these sales is also presented. After selling Sunflowers—a work deeply loved by the family—to London’s National Gallery, Jo stopped selling Van Gogh’s works and shifted towards preserving the collection. Theo and Jo’s son, Vincent Willem, inherited this intention, establishing the Vincent van Gogh Foundation and dedicating himself to the creation of the museum.

Account Book of Theo van Gogh and Jo van Gogh-Bonger, 1889–1925 Van Gogh Museum (Vincent van Gogh Foundation) collection

This time, from the Van Gogh family collection that has been passed down in this way, more than 30 Van Gogh works are displayed, along with the Van Gogh brothers’ collection, newly gathered works by related artists, Van Gogh’s letters, Jo’s ledger, and a 14-meter-wide immersive video section. The exhibition consists of five chapters:

-

From the Van Gogh Family Collection to the Van Gogh Museum

-

The Collection of Vincent and Theo, the Van Gogh Brothers

-

The Paintings and Drawings of Vincent van Gogh

-

Paintings Sold by Jo van Gogh-Bonger

-

Enriching the Collection: Acquisition of Works

Recently, I have been thinking about the issues of the secularization and re-sacralization of art. Modern art itself was born in the process of secularization. One might say this was fully realized in Impressionism. Even in Romanticism and Realism, secularization had progressed to a certain extent, but in their content, they still carried religiosity.

What is important in secularization is the affirmation of reality and the affirmation of life. In religion, life is sandwiched between original sin and judgment, and is governed by ethics before birth and after death. However, after the scientific revolution brought about by figures such as Copernicus, Galileo, and Newton, doubts arose regarding the Christian worldview, and there emerged a necessity to think about life without the framework of death. It can be said that thinking about life within this collapsing worldview formed the background for the birth of modern philosophy. In art, Japanese ukiyo-e played a significant role. Ukiyo-e transformed from “ukiyo” meaning “the sorrowful world” into secular paintings affirming this world. “Ukiyo” originally meant to grieve over the world, but it came to mean to enjoy the world.

Regarding the influence of ukiyo-e on artists after Impressionism, the multi-layered viewpoints not relying on linear perspective, flatness, bold compositions, combinations of color areas, depictions of plants, and the subtle wavering of surfaces created by washi paper are often pointed out as visual and formative elements. However, I think that for people from Christian cultural spheres, the greatest shock was in its affirmation of this world.

Indeed, Buddhism also has a strong aspect of world-denial, as in the saying “all life is suffering.” Even in Japan, which did not fully accept that, beliefs such as Pure Land faith and faith in Enma, where one is judged after death or seeks paradise, do exist. Nevertheless, compared to Christian societies, Japan had a far stronger thought of affirming life, and when people saw Japanese ukiyo-e—which lacked the heavy idea of original sin—they must have discovered an entirely different way of perceiving reality. That surely became a major trigger for the rise of the middle-class affirmation of life that emerged after the scientific, industrial, and civic revolutions. Without understanding the desperate Copernican shift in art from the negation of life to its affirmation, one cannot understand Impressionism.

Regrettably, Japan—the other protagonist—still does not seem to fully grasp what kind of impact it had on them even today. In Western art, the act of not depicting religious ethics or motifs at all, and instead thoroughly affirming reality, was truly revolutionary. It is like running freely without holding onto a religious cane. The reason they could drive forward in that way was none other than because they had found a new compass in ukiyo-e. Today, Impressionism is popular worldwide, but it is only natural that it is popular in Japan as well. It is like looking into our own mirror. Yet, what kind of mirror is it? In reality, I feel that even the Japanese themselves do not understand.

So then, how should Van Gogh be positioned within this current of life-affirmation in Impressionism? It is well known that Van Gogh once aspired to become a pastor. Precisely because of this, Van Gogh saw in ukiyo-e, created by Japanese people who lacked Christian ethical perspectives, a kind of reversed religiosity within its secular, life-affirming paintings. In that sense, it is only natural that Van Gogh was so obsessed with ukiyo-e, copied them, and moved to Arles in France in search of light similar to that of Japan.

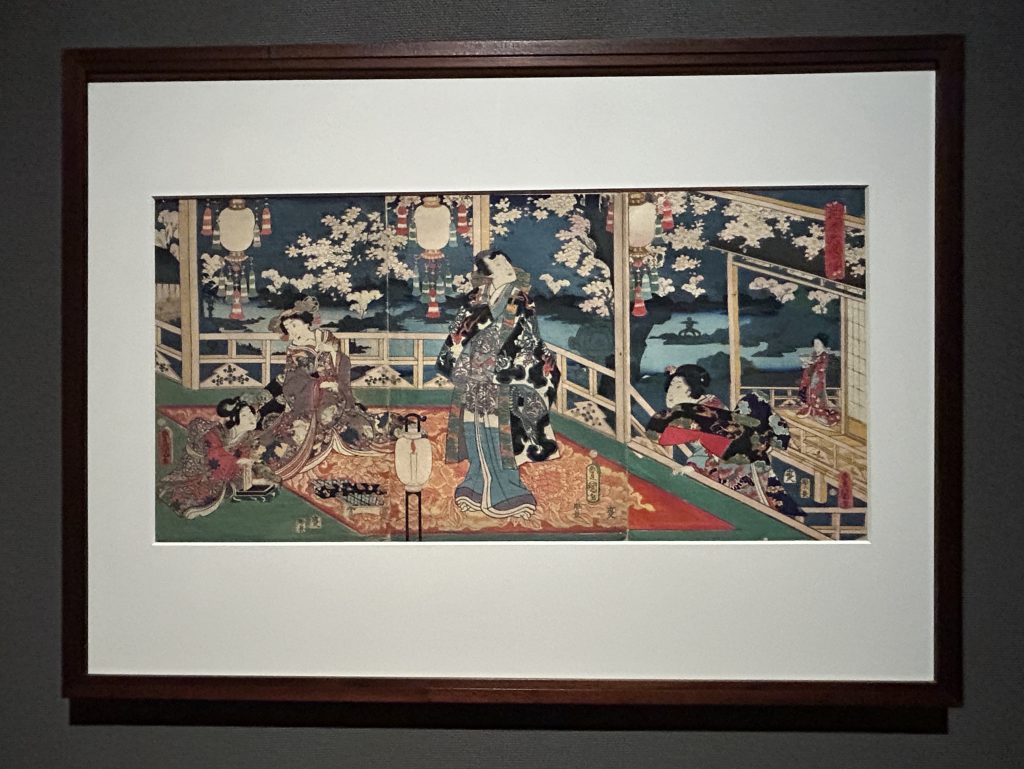

Utagawa Kunisada III (Utagawa Kunisada) The Flower Genji: Shadow of the Night, 1861 Van Gogh Museum (Vincent van Gogh Foundation) collection

In this exhibition, ukiyo-e prints collected by the Van Gogh brothers, including works by Utagawa Hiroshige and Utagawa Toyokuni III (Kunisada), are also introduced. It is said that more than 500 ukiyo-e prints were inherited by the Van Gogh family. Below the captions of the ukiyo-e collection exhibited this time, excerpts from Vincent’s letters to Theo are introduced. Here, I will present the full text included in the catalog:

“When you study Japanese art, you see a man who is undoubtedly wise, philosophical, and intelligent. What does this man spend his time doing? Studying the distance from the earth to the moon? No. Studying Bismarck’s politics? No. He studies a single blade of grass.

But starting from that grass, he depicts all plants, then the seasons and grand landscapes, and finally animals and human figures. He spends his entire life doing this, yet life is far too short to depict everything. Don’t you think what these Japanese people teach us seems almost like a new religion? They live so simply in nature, almost as if they themselves are flowers blooming in the fields. I feel that by studying Japanese art, one can become much happier and more cheerful, and by doing so, even we, bound by education and customs, can return to nature.”

(Letter 686, Vincent to Theo, September 23 or 24, 1888, Arles)

Indeed, Van Gogh saw a “new religion” in the subjects depicted by ukiyo-e and their attitude toward perceiving the world. Unlike Monet, who erased the self and depicted nature, or Renoir, who painted joyful moments of middle-class life affirming this world, Van Gogh’s works contained an unerasable self, deep emotions, and a resonance with Millet’s devout, simple rural life.

Color theories like complementary colors and pointillism, which were adopted by the Impressionists and Neo-Impressionists, were not strictly applied by Van Gogh; rather, they were transformed into a unique touch that only he could produce. When compared to the collections gathered by the Van Gogh brothers or to works by artists deeply related to him collected after his death, these differences become all the more pronounced.

And we Japanese, living in Japan, see in Van Gogh’s paintings a worldview different from that of “Impressionism as our mirror.” It is a mirror of ourselves seen through Van Gogh’s worldview. Yet in either case, it was Japan that first cast the light. It is no doubt that Impressionist works still bring happiness to people around the world today, and Van Gogh’s works continue to move people deeply.

That is why we must ask ourselves: What meaning did the affirmation of life depicted by Japanese art have for the world? And what significance does it hold for today’s art and today’s world? That is a question we ourselves must answer.