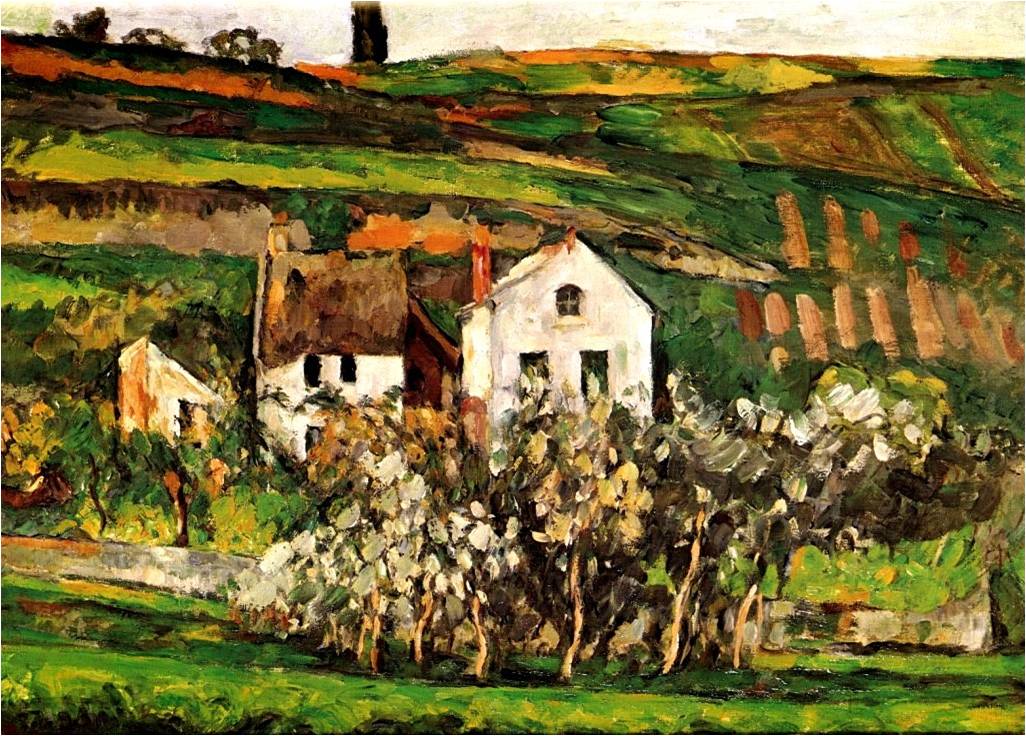

Fig. 1 Paul Cézanne, Small Houses at Auvers-sur-Oise, 1873-74.

Among all paintings by Paul Cézanne (1839-1906), the one that most evokes the view from a train window is probably Small Houses at Auvers-sur-Oise (1873-74) (Fig. 1).

In fact, in this work, the ridgelines stand out across the entire screen, and the repeated sideways brushstrokes give a sense of rapid horizontal movement. In Addition, from the background toward the foreground the objects appear to become distorted, dotted, and disappear. Furthermore, the line drawn connecting the bottom of the canvas from the left to the right makes the foreground vanished, giving the impression that the viewer’s feet are floating. These are very similar to the scenery seen from the window of a train.

This is important because it shows that Cézanne was the first among the Impressionist painters to respond to the influence of the railway not only in his subjects but also in his forms.

Fig. 2 Camille Pissarro, The Road near the Railway, Effect of Snow, 1873.

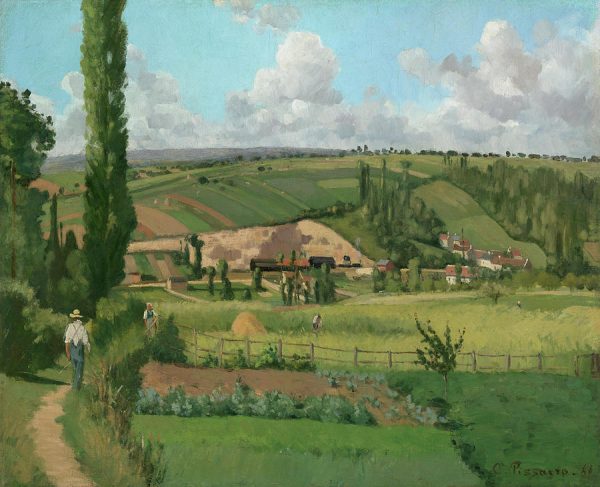

図3 Camille Pissarro, Landscape at Les Pâtis, Pontoise, 1868.

Fig. 3 (detail)

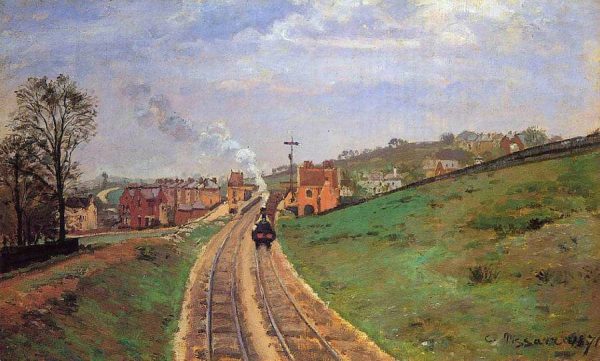

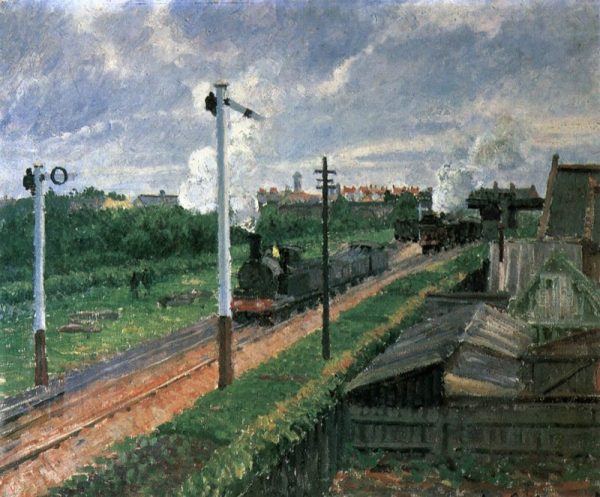

Fig. 4 Camille Pissarro, Lordship Lane Station, Dulwich, 1871.

Fig. 5 Camille Pissarro, The Train, Bedford Park, 1897.

Basically, in painting, the influence of unfamiliar object first appears in the subject and then in the form. Because it is easier to paint what you see than to paint what you have internalized.

In the mid-19th century, steam locomotives, which rushed at abnormal high speeds with loud roaring, were generally regarded as ugly monsters. Therefore, even when impressionist painters depicted railways, they were initially somewhat reluctant.

For example, in Camille Pissarro’s The Road near the Railway, Effect of Snow, (1873) (Fig. 2), the train is not depicted, but rather implied by the accompanying telegraph poles and wires. Even when portraying the train itself, in Pissarro’s Landscape at Les Pâtis, Pontoise (1868) (Fig. 3), the train is shown small and far away, and is not shown facing forward but sideways.

As the fear had been diminished, steam locomotives began to be depicted facing forward, as in Pissarro’s Lordship Lane Station, Dulwich (1871) (Fig. 4). Furthermore, as the resistance had been overcome, steam locomotives began to be portrayed large and positively, as in Pissarro’s The Train, Bedford Park (1897) (Fig. 5).

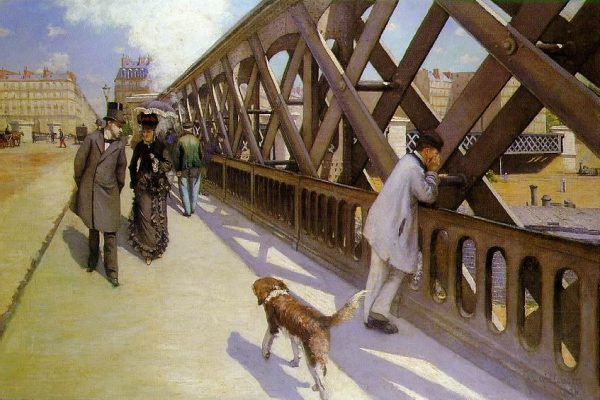

In this context, Gustave Caillebotte’s The Europe Bridge (c. 1876) (Fig. 6) and Édouard Manet’s The Railway (1873) (Fig. 6), which have steam locomotives as their main subject but suggest their presence through the spewing steam, can be said advanced yet transitional works.

Fig. 6 Gustave Caillebotte, The Europe Bridge, c. 1876.

Fig. 7 Édouard Manet, The Railway, 1873.

Later, some painters began to shift their focus from depicting trains from the outside to expressing railway journeys from the inside. In other words, they began to paint scenes influenced by the view from a moving train. The sooner this transition from subject to form was achieved, the more advanced the psychological adaptation to the new reality induced by the railway.

As examples, let’s look at Cezanne, Claude Monet (1840-1926), and Edgar Degas (1834-1917).

Fig. 8 A train leaving Bonnières station

(Filmed by the author on August 28, 2006)

Fig. 9 Paul Cézanne, The Ferry at Bonnières, 1866.

Fig. 10 Paul Cézanne, The Railway Cutting with Mont Sainte-Victoire, c. 1870.

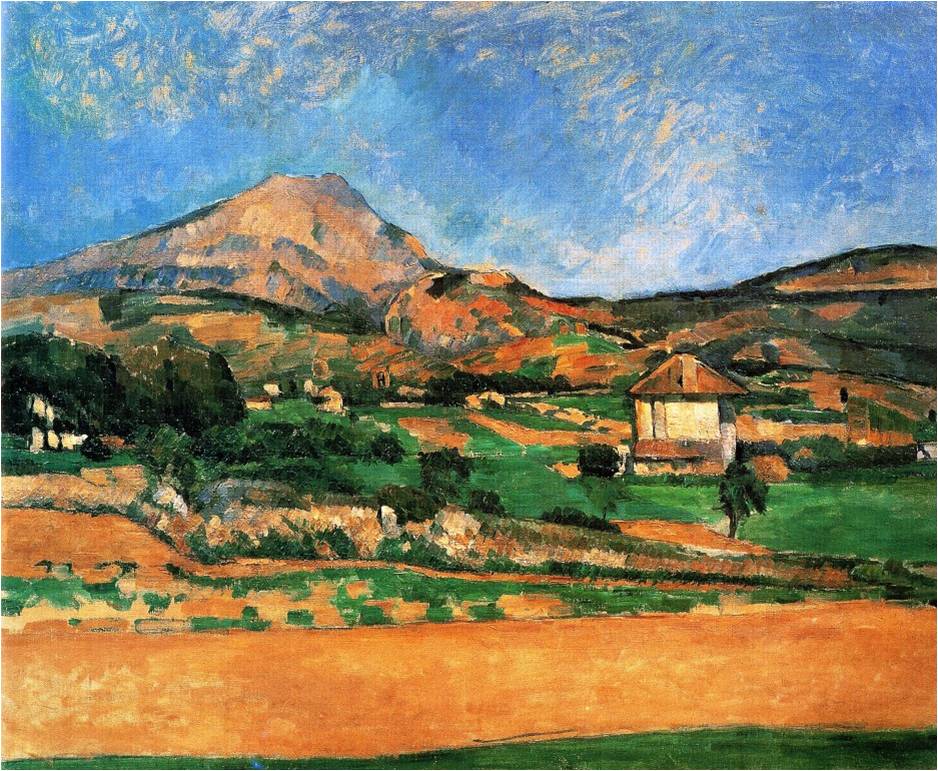

Fig. 11 Paul Cézanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire view from Valcros, 1878-79.

First, Cézanne painted The Ferry at Bonnières (Fig. 8) in the summer of 1866, when he was in his late twenties. As we have seen in the section 2, in this painting, although it is not obvious at first glance, the modern telegraph pole and electric wires in the center of the screen suggest a railway station, which contrasts with the pre-modern ferry at the bottom of the canvas (Fig. 9). Therefore, this work is the earliest painting to feature the railway as a subject among all the works by Impressionist painters.

In The Railway Cutting with Mont Sainte-Victoire (c. 1870) (Fig. 10), too, the modern railway cutting in the center of the screen is contrasted with the pre-modern Mont Sainte-Victoire on the right side. Interestingly, this work depicts the cutting of the Aix-Lognac line, about 100 meters away, as seen from the garden of Jas de Bouffan, the residence where Cézanne lived in his hometown of Aix. In short, Cézanne daily witnessed steam locomotives passing through this cutting.

Fig. 12 Mont Sainte-Victoire seen from the train window on the Aix-Marseille line

(filmed by the author on August 26, 2006)

Moreover, Cézanne began to create a landscape series after viewing from a moving train on the newly opened Aix-Marseille line in his hometown of Aix. In fact, in a letter dated April 14, 1878, to his childhood friend Émile Zola, he wrote the following:

Where the train passes close to Alexis’s country house, a stunning motif appears on the East side: Ste Victoire and the rocks that dominate Beaurecueil. I said: “What a lovely motif” (1).

It was precisely after 1878 that Cézanne, at around the age of 40, suddenly began to paint a large number of Mont Sainte-Victoire. Therefore, it is highly likely that Cézanne’s series of paintings of this mountain was inspired by the visual transformation brought about by the railway. One of the earliest works in this series is Mont Sainte-Victoire view from Valcros (1878-79) (Fig. 11).

Actually, in this work, as in Small Houses at Auvers-sur-Oise, (Fig. 1), from background toward the foreground, the brushstrokes emphasize the repetition horizontally, creating a sense of horizontal movement. Furthermore, the foreground disappears due to the line connecting the left and the right of the bottom of the canvas, giving the impression that the viewer’s feet are hovering. These evoke the visual sensation of riding a train (Fig. 12).

These three works show that the railway were deeply rooted in Cézanne’s daily life from his youth. We can also sense that the influence of the railway on Cézanne’s works shifted from the subject to the form. In the latter, the modernity of the railway has been completely sublimated.

Fig. 13 Claude Monet, A Train in the Country, 1870.

Fig. 14 Claude Monet, Saint-Lazare Station, Arrival of a Train, 1877.

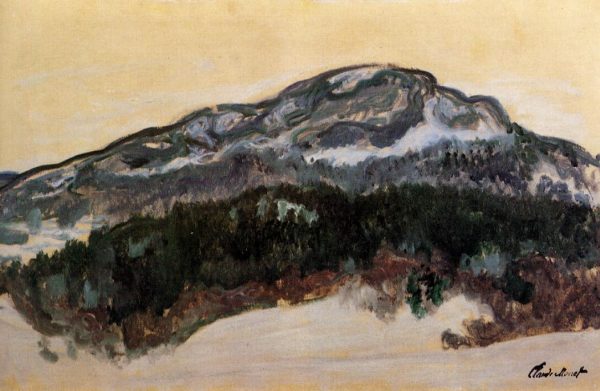

Fig. 15 Claude Monet, Mount Kolsaas, Norway, 1895.

Generally, it has been said that among the Impressionists, Claude Monet was the most enthusiastic about the railway. This is mainly due to his famous series of paintings which he prominently featured steam locomotives arriving at Saint-Lazare station dated from 1877 to 1878.

First, Monet painted his first train in 1870, titled A Train in the Country (Fig. 13). At this time, it seems that even Monet found steam trains difficult to approach, so the train is shown small and sideways in the distance, with the steam locomotive itself hidden behind trees. In this painting, as in Cezanne’s The Ferry at Bonnières (Fig. 9), the modern railway in the background is contrasted with the pre-modern natural plain and the strolling people in the foreground.

On the other hand, at the third Impressionist exhibition in 1877, Monet presented a series of paintings with the central subject being trains arriving at Saint-Lazare station, one of Paris’s main railway stations. In particular, Saint-Lazare Station, Arrival of a Train (1877) (Fig. 14) shows progress in adaptating the modernity of the railway, as evidenced by the bold depiction of a huge steam locomotive facing forward in the foreground.

As a side note, Émile Zola (1840-1902), who was a close friend of Cézanne and well-acquainted with all the Impressionist painters, praised Monet’s “Saint-Lazare Station” series in his article “An Exhibition—The Impressionist Painters” on April 19, 1877, during the third Impressionist exhibition. Since Cézanne also exhibited his works at this exhibition, he was undoubtedly known to Monet’s railway station series and Zola’s praise of it.

M. Claude Monet is the most marked personality of the group. This year he is exhibiting some superb station interiors. One can hear the rumble of the trains surging forward, see the torrents of smoke winding through vast engine sheds. This is the painting of today: modern settings beautiful in their scope. Our artists must find the poetry of railway stations as our fathers found the poetry of forests and rivers (2).

Moreover, Monet also worked on a series of landscape paintings after viewing sceneries from a speeding train. In fact, in a letter to Alice Monet dated February 3, 1895, he wrote:

The road was often monotonous and the snow, eternal since Paris, a little tiring at the end; however, my last day on the train allowed me to see some extraordinary things, even more beautiful than Christiania (3).

One of the series of 13 paintings that Monet produced at the time was Mount Kolsaas, Norway (1895) (Fig. 15). Therefore, it is highly likely that this work reflects the visual transformation brought about by the railway travel.

Actually, in this painting, as in Cézanne’s Small Houses at Auvers-sur-Oise (Fig. 1), the contours are blurred and the brushstrokes are repeated horizontally, giving a sense of horizontal movement. Additionally, the large horizontal space at the bottom of the canvas makes the foreground disappear, giving the viewer the impression of gazing at the landscape without body.

These also evoke the visual sensation during riding a train. In a word, Monet fully assimilated the modernity of the railway in this painting.

Fig. 16 Edgar Degas, Beach Scene, 1869-70.

Fig. 17 Edgar Degas, The Racecourse, Amateur Jockeys, 1876-87.

Fig. 18 Edgar Degas, Landscape, 1892.

Edgar Degas, who was friends with Cézanne and Monet, painted the steam ship, which was put into practical use earlier than the steam train, in his Beach Scene (1869-70) (Fig. 16). In this work, two steam ships are depicted small and sideways in the distance, spewing black smoke.

Degas also painted the steam train. In fact, in The Racecourse, Amateur Jockeys (1876-87) (Fig. 17), a steam train rushing by on the left side of the screen, spewing white smoke, is depicted small and sideways in the distance. In this painting, as in Cézanne’s The Ferry at Bonnières (Fig. 9) and Monet’s A Train in the Country (Fig. 13), the modern locomotive in the background is contrasted with the pre-modern horses and coach in the foreground.

Degas also produced a series of landscape paintings inspired by the sceneries he saw while riding on the train. In fact, in September 1892, he stated:

[These 21 landscapes are] the fruits of my journeys this summer. I stood at the doors of the coaches and I looked round vaguely. That gave me the idea to do the landscapes (4).

One of the 21 paintings that Degas created at the time was Landscape (1892) (Fig. 18). Therefore, it is certain that this work reflects the transformation of vision induced by the railway.

Actually, in this painting, as in Cezanne’s Small Houses at Auvers-sur-Oise (Fig. 1) and Monet’s Mount Kolsaas, Norway (Fig. 15), from the background toward the foreground, the contours are blurred and the brushstrokes are quickly swept sideways, giving a sense of horizontal movement. Additionally, the foreground disappears due to the large horizontal blank space at the bottom of the canvas, giving the viewer the impression of viewing the landscape while flying.

These also recollect the visual sensation during riding a train. In short, Degas perfectly internalized the modernity of the railway in this painting.

As we have seen above, among the impressionist painters who first seriously took up the railway in France, Cézanne, Monet, and Degas were experienced the transition of influence by the railway from the subject to the form in their paintings. What is interesting is that they all expressed the formative influence in their series of works. This may be because whoever tries to apply the transformed visual perception while riding a moving train to paint the natural scenery after getting off the train will naturally end up producing many works, repeatedly confirming that sensation with the same object.

In any case, among these three artists, it was Cézanne who was the earliest to transition about the influence of the railway from the subject matter to the formal representation.

In fact, Cézanne first used the railway as a subject in The Ferry at Bonnières (Fig. 9) in 1866, and he first expressed the altered vision induced by the railway as a form in Small Houses at Auvers-sur-Oise (Fig. 1) between 1873 and 1874 (or at the latest in Mont Sainte-Victoire view from Valcros (Fig. 11) between 1878 and 1879). Both of these works were earlier than those of Monet and Degas, who are well known as “painters of modern life.”

Considering the abundance of landscape paintings, there is no doubt that Cézanne had a love of nature. However, at the same time, it can be assumed that this is precisely why he was able to respond so sensitively to the various changes brought about by the modern railway – both in terms of subject and form. In this sense, Cézanne is also undoubtedly one of the “painters of modern life.”

Notes

(1) Paul Cézanne, Correspondance, recueillie, annotée et préfacée par John Rewald, Paris, 1937; nouvelle édition révisée et augmentée, Paris, 1978, p. 165; English translated by Marguerite Kay, New York, 1941; new edition revised and enlarged, New York, 1976; New York, 1995, pp. 158-159.

(2) Émile Zola, “Une exposition: les peintres impressionnistes” (19 avril 1877), in Notes parisiennes (1877), in Œuvres complètes, VIII, Paris: Nouveau Monde, 2003, pp. 629-630. (Translated by Sylvie Gache-Patin, A Day in the Country: Impressionism and the French Landscape, Los Angeles Country Museum of Art, 1984; New York, 1990, p.116.)

(3) Daniel Wildenstein, Claude Monet: biographie et catalogue raisonné, III, Lausanne-Paris: La Bibliothèque des arts, 1979, p. 279.

(4) Edgar Degas, Lettres de Degas, recueillies et annotées par Marcel Guérin, Paris, 1931; nouvelle édition, Paris, 1945, pp. 277-278.

【Related Posts】

■ Tomoki Akimaru, Cézanne and the Railway (1) – (7): A Transformation of Vision in the 19th Century.

Cézanne and the Railway (1): A Hidden Origin of Modern Vision

Cézanne and the Railway (2): The Earliest Railway Painting Among French Impressionists

Cézanne and the Railway (3): His Railway Subject in Aix-en-Provence

Cézanne and the Railway (4): His Railway Subject in Médan, Pontoise, Gardanne, and L’Estaque

Cézanne and the Railway (5): A Stylistic Analysis of His Pictorial Form

Cézanne and the Railway (6): The Influence of the Machine on the Shift from Subject to Form

Cézanne and the Railway (7): What is the Realization of Sensations?

■ Tomoki Akimaru, Fauvism and the Automobile: A Transformation of Vision in the 20th Century.

● Marie Rauzy — A contemporary French painter descended from Paul Cézanne