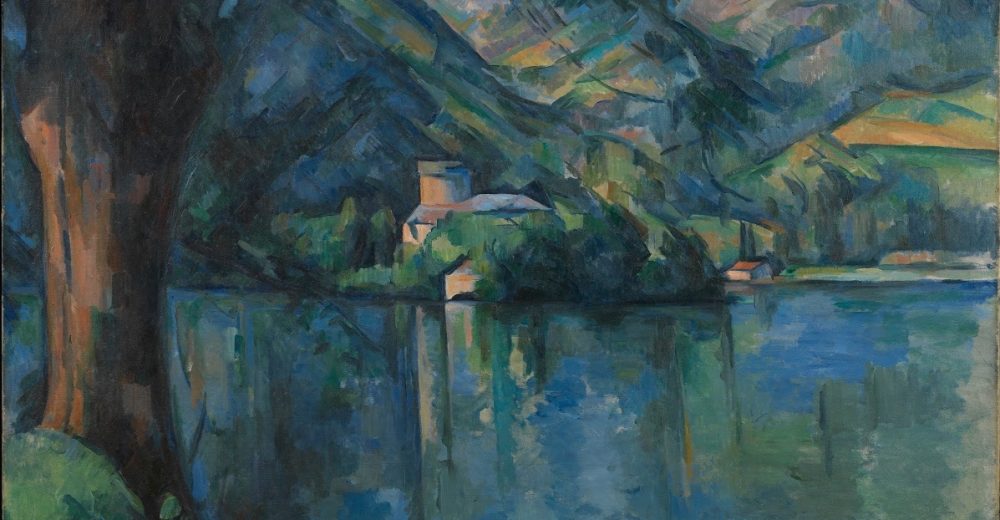

Fig. 1 Paul Cézanne, Lake Annecy, 1896.

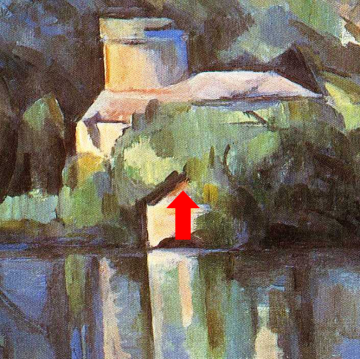

Fig. 1 (detail)

How was Paul Cézanne’s artistic expression influenced by the railway? Here, we will analyze Cézanne’s paintings.

First, in Lake Annecy (1896) (Fig. 1), a small red dot is pointed on the top of the nearby roof of a building in the background at the center of the screen. From this central point of the composition toward the foreground the brushstrokes become rougher, with the nearest tree on the left side of the screen being painted with larger brushstrokes. In addition, the foreground is unclear, and it looks as if the viewer is floating in the air and looking at this landscape.

These sensations of background being static, of nearer objects being dynamic, and of the foreground disappearing and one’s feet off the ground, is very similar to the vision from the window of a moving train.

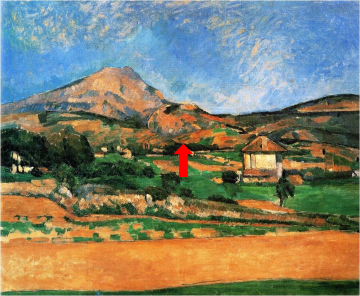

Fig. 2 Paul Cézanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire and Large Pine, c. 1887.

Fig. 2 (detail)

Second, in Mont Sainte-Victoire and Large Pine (c. 1887) (Fig. 2), a small black dot is depicted on the slope of Mont Sainte-Victoire in the background at the center of the screen. In this work too, the brushstrokes become rougher from this center point of the composition toward the foreground, with the outlines of the nearest tree trunk and branches are blurred. Additionally, the foreground is ambiguous, and it looks as if the viewer is suspended in midair and looking at this scenery. Furthermore, the tree on the left side of the screen can be seen as if it is being viewed horizontally or as if it is being viewed from below.

These sensations of background less moving, of nearer objects moving from side to side, of the foreground vanishing and one’s feet leaving the ground, and of the visual angle swaying up and down, are very alike to the visual perception while riding a train.

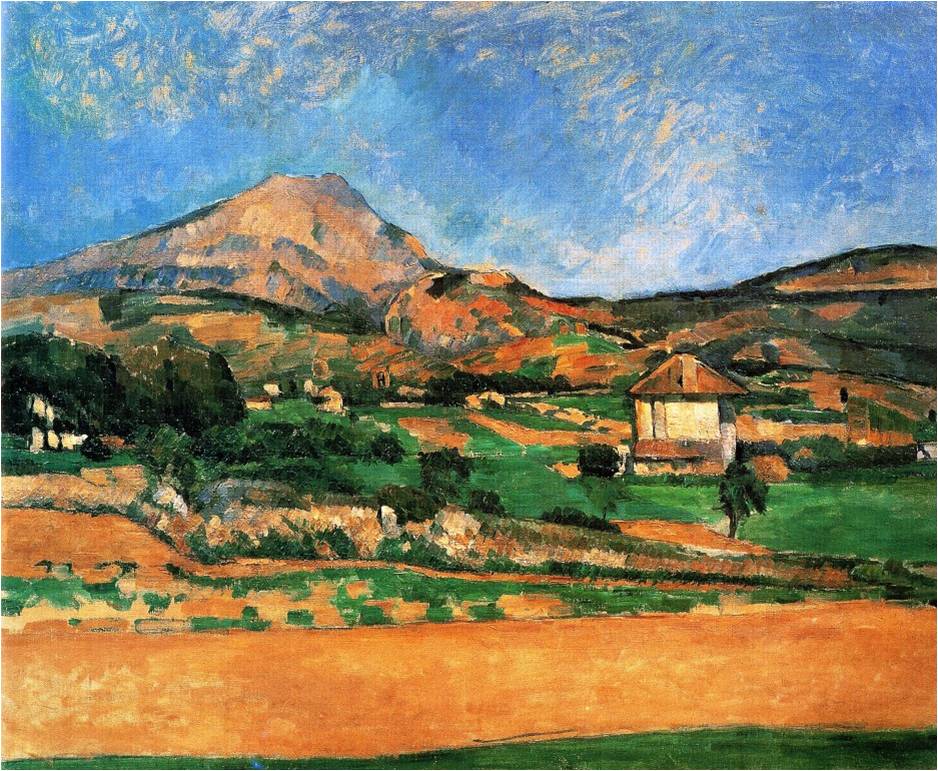

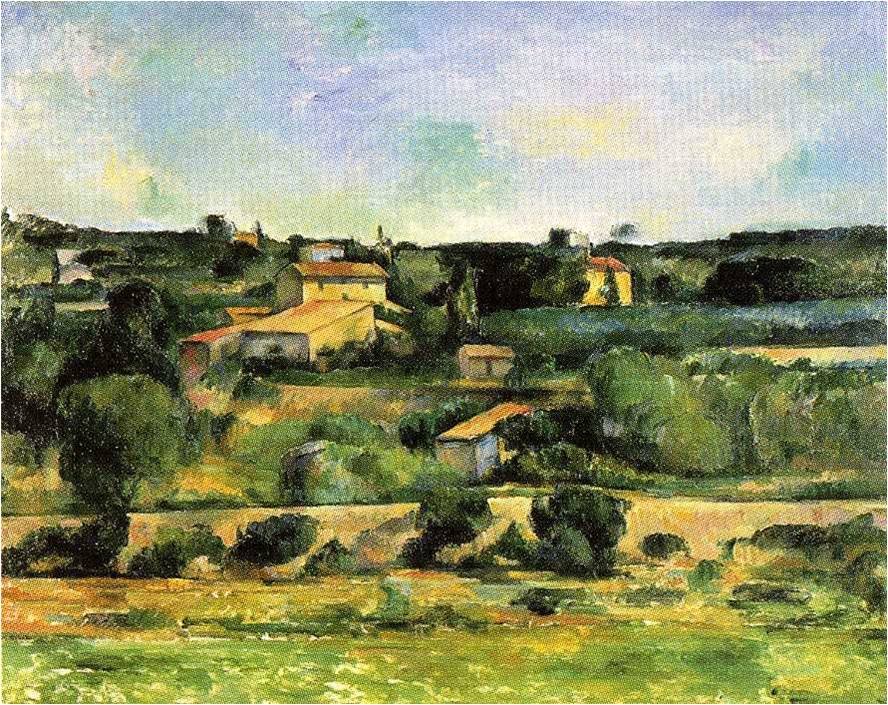

Fig. 3 Paul Cézanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire view from Valcros, 1878-79.

Fig. 3 (detail)

Fig. 4 The site photo of Fig. 3

(Photographed by the author on August 24, 2006)

Third, in Mont Sainte-Victoire view from Valcros (1878-79) (Fig. 3), there is a small red dot in the background on the horizon at the center of the screen. In this work, from the centerpoint of the composition toward the foreground, the brushstrokes emphasize the repetition horizontally. Particularly, the house on the middle right side of the screen appears to be moving to the left due to the repeated brushstrokes on the right side. Moreover, near the foreground, the repeated horizontal brushstrokes turn into horizontal ridgelines connecting the left and right sides of the screen. As a result, the foreground is not clear, and the viewer appears to be hovering and looking at the scene.

These sensations of horizontal ridgelines being noticeable, of nearer objects moving horizontally, of the foreground being lost and one’s feet levitating off the ground, are very resembling to the feeling of enjoying the view from a train window.

Actually, the Aix-Marseille line, on which Mont Sainte-Victoire can be seen while traveling, opened on October 15, 1877 (Fig. 5). About half a year later, in a letter dated April 14, 1878 to Émile Zola, Cézanne praised Mont Sainte-Victoire as seen from the window of a train speeding on this line as follows:

Where the train passes close to Alexis’s country house, a stunning motif appears on the East side: Ste Victoire and the rocks that dominate Beaurecueil. I said: “What a lovely motif” (1).

It was after 1878 that Cézanne began his series of paintings of Mont Sainte-Victoire in his hometown of Aix-en-Provence, and Mont Sainte-Victoire view from Valcros (1878-79) (Fig. 3) is one of his earliest works. At this time, Cézanne was around 40 years old. Given that he suddenly began painting this mountain, which he had not painted until then, it is highly likely that Cézanne’s Mont Sainte-Victoire series was inspired by the view from the train window on this newly opened railway line.

Fig. 5 Mont Sainte-Victoire seen from the train window on the Aix-Marseille line

(filmed by the author on August 26, 2006)

Fig. 6 A Train Window Scenery on the Aix-Marseille line

(filmed by the author on August 26, 2006)

As mentioned above, the stylistic characteristics of Cézanne’s paintings highly look like to the visual characteristics experienced during a train ride.

In fact, when looking through the window of a running train, the scenery flows from side to side, the nearer objects move fast, and they become distorted, spotted, and disappeared. As a result, the foreground is lost, and the viewer gets the feeling of floating through the air. The viewing angle also changes up and down depending on the wave of the land (Fig. 5, Fig. 6) (2).

The visual transformation induced by the railway was a new reality that the development of modern technology in the second half of the 19th century brought to mankind. Cézanne’s visual sensitivity was so keen to respond to such revolutionary yet ordinary changes that most people tend to overlook.

Fig. 7 Paul Cézanne, In the plain of Bellevue, 1885-88.

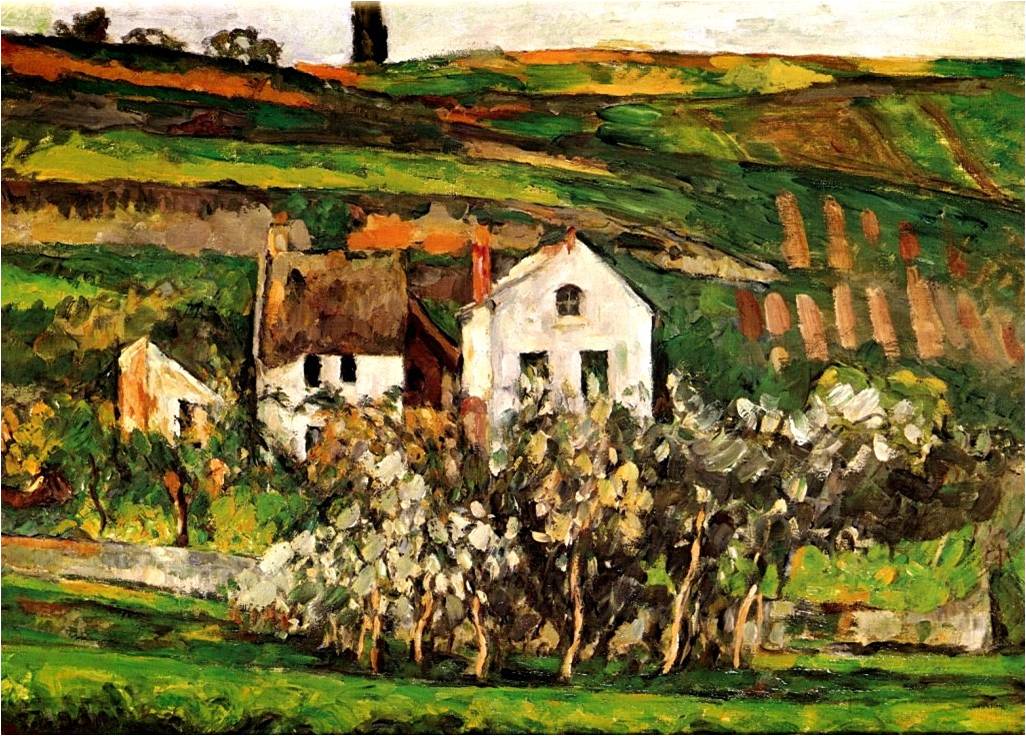

Fig. 8 Paul Cézanne, Small Houses at Auvers-sur-Oise, 1873-74.

Indeed, Cézanne’s paintings often have a sense of horizontal movement, with repeated brushstrokes and layering ridgelines, and often the viewer appears to be floating in the air, with the unclear foreground.

For example, in In the plain of Bellevue (1885-88) (Fig. 7), the horizontal edges stand out across the entire screen. Additionally, a large horizontal blank space in the foreground obscures the footing, making it seem as if the viewer is looking at the landscape from the air.

Similarly, in Small Houses at Auvers-sur-Oise (1873-74) (Fig. 8), the horizontal ridges are emphasized all over the screen. The brushstrokes are repeated on the right side of the houses, giving the impression of horizontal movement, and the trees seem to be deformed, pointillized, and vanished. Furthermore, the foreground is cut off by a horizontal ridge, making it unclear where the viewer stands, giving the feeling that the viewer is glancing at the landscape without a body.

Perhaps among all of Cezanne’s paintings, these two in particular evoke images of the scenery passing by as seen from the window of a speeding train.

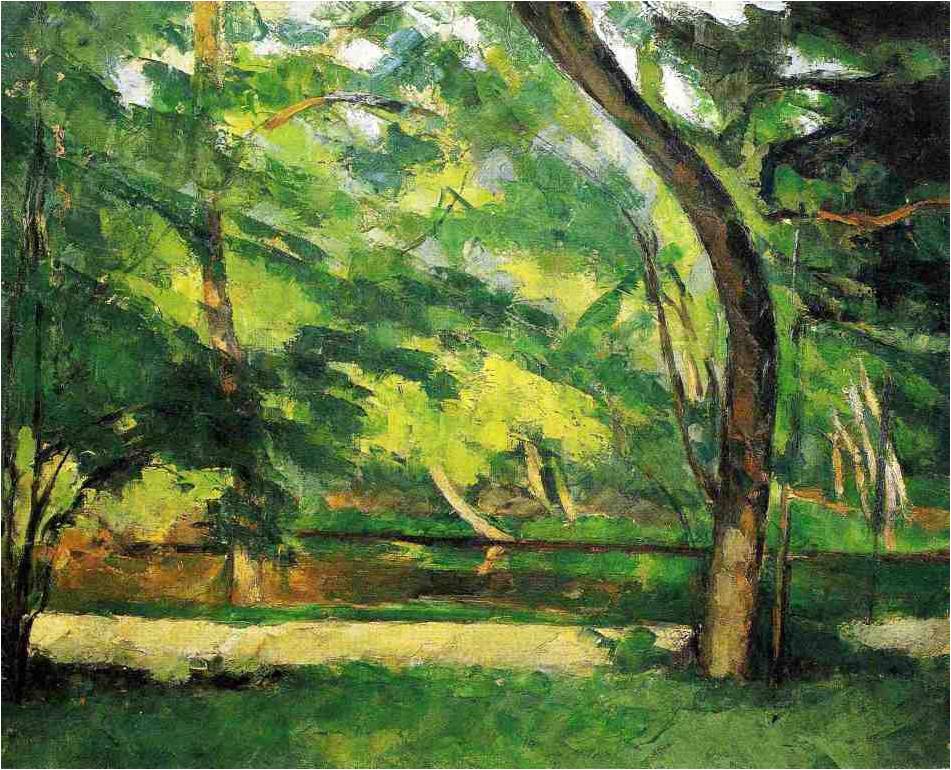

Fig. 9 Paul Cézanne, The Sister’s Pond at Osny, 1877.

Fig. 10 Paul Cézanne, Gardanne (Horizontal View) , c. 1885.

Moreover, in Cézanne’s paintings, the objects are often crooked or distorted sideways.

In fact, in The Sister’s Pond at Osny (1877) (Fig. 9), the closest tree on the right side of the screen appears to be curved largely left and right, with blurred outlines. In addition, the horizontal ridges of the pond and bank on the lower side of the screen are put stress on, and the foreground is unclear and making the viewer’s footing feel unstable.

In Gardanne (Horizontal View) (c. 1885) (Fig. 10), all buildings seem to be tilted clearly to the left. Furthermore, the horizontal ridgelines are noticeable in the distance and near, and the foreground is unclear, giving the viewer the impression that the ground is unsteady.

These visions are unusual, but everyone must have experienced the world in this way while riding a train.

Fig. 11 Paul Cézanne, The Card Players, 1896.

Fig. 12 Paul Cézanne, Apples and Oranges, c. 1899.

Moreover, while riding on a train, the passenger’s perspective also shifts as the train sways. At the same time, because the train is moving in a straight line at high speed, the passengers’ vision becomes abstracted, and the object is perceived as a mass. This tendency for the world to sway and for objects to become abstracted can also be found in Cézanne’s indoor paintings.

For instance, in The Card Players (1896) (Fig. 11), the right side of the field of view seems to be floating up, and the men playing cards and table appear to be leaning to the left. Furthermore, the hats of the two men and the bottle suggest a cylinder, a cone, and a sphere.

As a side note, in a letter to Émile Bernard dated April 15, 1904, Cézanne explains his approach to the abstraction of objects as follows:

Treat nature by means of the cylinder, the sphere, the cone, everything brought into proper perspective so that each side of an object or a plane is directed towards a central point (3).

And in Apples and Oranges (c. 1899) (Fig. 12), the table is tilted to the left so that the fruits and other items on it look as if they might fall off at any moment. In this painting, the fruits and items on the table are viewed horizontally, whereas the table itself appears to be seen from above.

These sensations of the world shaking, of shapes being abstracted and deformed, and of multiple perspectives are very familiar to the person experienced to view the scene inside a speeding train.

In fact, The Card Players (Fig. 11) and Apples and Oranges (Fig. 12) each have a central point in the composition. In Fig. 11, there is a small white dot under the light reflection of the bottle at the center of the screen. In Fig. 12, there is also a small red dot on the cavity of the apple in the center of the screen. As with the landscape paintings, it can be assumed that Cézanne focused his attention on the centerpoint of the composition in the indoor paintings, and that he was recalling the sensation of the world swaying while riding the train.

Of course, Cezanne did not simply paint the outdoors and indoors he saw while riding the train. In this case, it is more significant that he applied the vision transformed by the railway he experienced to the natural landscape after getting off the train. This is because the visual transformation induced by the railway was internalized and expressed as a painting. Therefore, the new painting forms that Cézanne created in the second half of the 19th century must be taken into consideration for the influence of the new visual reality brought about by the railway, which developed at the same time.

Notes

(1) Paul Cézanne, Correspondance, recueillie, annotée et préfacée par John Rewald, Paris, 1937; nouvelle édition révisée et augmentée, Paris, 1978, p. 165; English translated by Marguerite Kay, New York, 1941; new edition revised and enlarged, New York, 1976; New York, 1995, pp. 158-159.

(2) Wolfgang Schivelbusch, Geschichte der Eisenbahnreise: Zur Industrialisierung von Raum und Zeit im 19. Jahrhundert, München, 1977; Frankfurt am Main, 2004; English edition, The railway journey: the industrialization of time and space in the nineteenth century, University of California Press, 2014.

(3) Paul Cézanne, Correspondance, recueillie, annotée et préfacée par John Rewald, Paris, 1937; nouvelle édition révisée et augmentée, Paris, 1978, p. 300; English translated by Marguerite Kay, New York, 1941; new edition revised and enlarged, New York, 1976; New York, 1995, p. 301.

【Related Posts】

■ Tomoki Akimaru, Cézanne and the Railway (1) – (7): A Transformation of Vision in the 19th Century.

Cézanne and the Railway (1): A Hidden Origin of Modern Vision

Cézanne and the Railway (2): The Earliest Railway Painting Among French Impressionists

Cézanne and the Railway (3): His Railway Subject in Aix-en-Provence

Cézanne and the Railway (4): His Railway Subject in Médan, Pontoise, Gardanne, and L’Estaque

Cézanne and the Railway (5): A Stylistic Analysis of His Pictorial Form

Cézanne and the Railway (6): The Influence of the Machine on the Shift from Subject to Form

Cézanne and the Railway (7): What is the Realization of Sensations?

■ Tomoki Akimaru, Fauvism and the Automobile: A Transformation of Vision in the 20th Century.

● Marie Rauzy — A contemporary French painter descended from Paul Cézanne