Marie Rauzy

Having a famed ancestor is hard for anyone. That is because aside from being looked upon chiefly as the descendent of a renowned person, the poor soul is always being compared to that grand forebear.

At the same time, is it not also possible that an unknown aspect, indeed the essence, of that great ancestor can be revealed through their descendants? A perfect example of this is Marie Rauzy, whose great-great-grandfather was Paul Cézanne.

Marie Rauzy was born in 1961 in Marseilles, France. Captivated by painting from an early age, Marie made up her mind when she was 18 to become a painter. In 1988 she graduated from the prestigious École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris. The previous year, she had already launched her career as an artist, and to this day, she has had solo exhibitions in France, Belgium, Germany, China, Japan, and other countries. She currently lives and works near the forest of Fontainebleau.

Alongside her creative work as a painter, Marie has been teaching painting to children as an art teacher at an elementary school in Paris for over 30 years since 1989. She is an expert in art education, and in 2019, she published Cut, Stick, and Draw, a primer text for introducing painting to children.

Marie is the great-great granddaughter of the painter Paul Cézanne. Cézanne’s son was also named Paul Cézanne. His daughter was Aline Cézanne; her daughter was Monique Gobert; and her daughter is Marie Rauzy. Yet for many years, Marie did not reveal that she was a descendent of the great master Cézanne. That was because she did not want to be suspected of trying to gain attention as an artist by making use of his name. Marie only publicly made known her bloodline in 2006, after she had already established her career as a painter and an art educator. The occasion was a major retrospective commemorating the 100th anniversary of Cézanne’s death held in his birthplace of Aix-en-Provence.

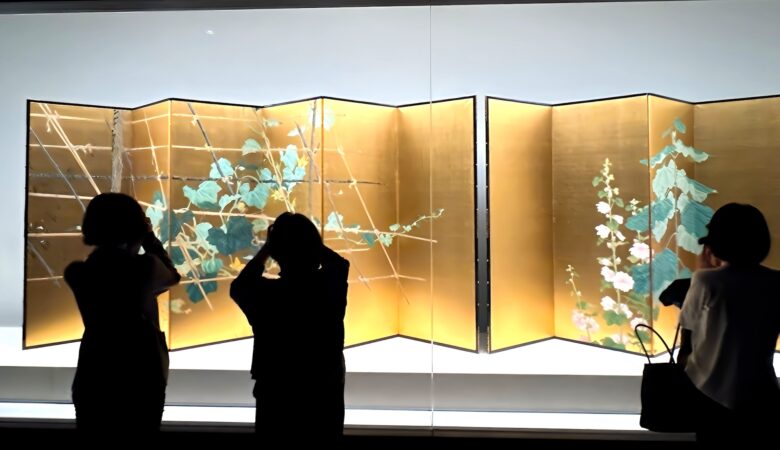

Fig.1 Marie Rauzy, The Static Hedge, 2012.

Fig.2 Marie Rauzy, The Right Moment 1, 2017.

Fig.3 Marie Rauzy, Momentary Scene #1, 2018.

Fig.4 Marie Rauzy, Separation in a Small Space 8, 2020.

One of Marie’s techniques is to depict the background of a painting as if it is passing by at a high speed. A representative example of this painting style is her series entitled “Speed of Landscapes.” The horizontally blurred and opaque depiction inevitably brings to mind the scenery seen from the window of a train, car, or airplane moving horizontally at high speed (Fig.1-Fig. 4).

These are outdoor landscape paintings, but she also uses the same technique for indoor still-life paintings (Fig.5-Fig.8). In these paintings, the central motif is in focus while the background is a passing flash. These depictions also give us the sensation of seeing the passing scenery from a fast-moving train, car, or airplane. Especially, when travelling by airplane, everyone probably feels that same sense of our immobility inside the plane versus the blurry speed outside.

Fig.5 Marie Rauzy, Golden Pot, 2017.

Fig.6 Marie Rauzy, Digestion, 2017.

Fig.7 Marie Rauzy, Bouquet, 2019.

Fig.8 Marie Rauzy, Apples and Pots, 2020.

These depictions would have been impossible to express in the world before the appearance of fast-moving machines. For example, it would be unthinkable for such depictions to appear in Italian Renaissance paintings since no artist would have had that experience. Of course, an artist riding a galloping horse may have seen such a scene momentarily, but that would have been only an extraordinarily rare experience. It is safe to say that the sense of such an extremely clear separation between the main motif and its background would not have been imagined in everyday consciousness.

In that respect, what she has represented in these paintings is the sense of “modernity.” In other words, Marie is what Baudelaire called a “painter of modern life.”

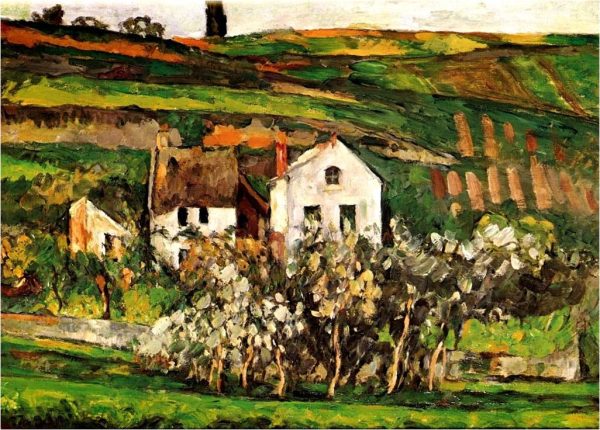

Fig.9 Paul Cézanne, Small Houses in Auvers-sur-Oise, 1873-74.

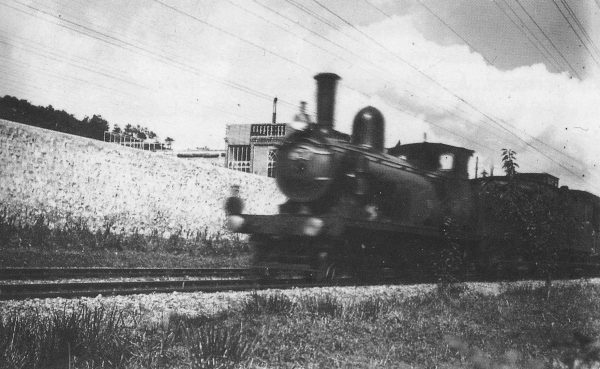

Fig.10 Photograph by Emile Zola, French steam locomotive of the late 19th century, date unknown.

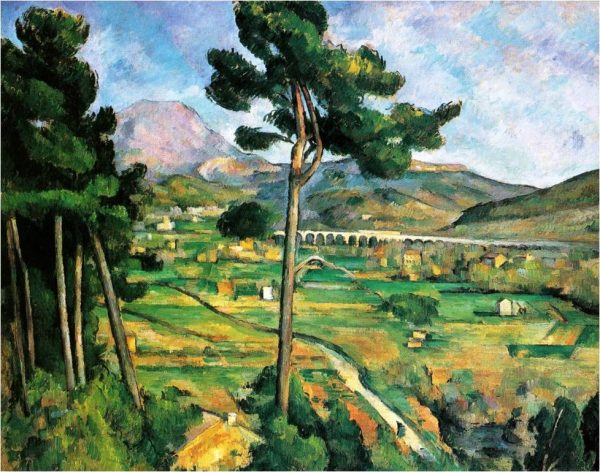

It is worth noting that Cézanne also created works in which the background appears to pass by quickly (Fig. 9). This painting is a representative example of the formal characteristics of Cézanne’s work. In contrast to the small number of lines that run vertically through the painting, the ridgelines overlap horizontally, and brushstrokes are also often repeated from side to side. These techniques create a sense of motion, as if the landscape or the viewer himself were moving sideways at high speed. In other words, it is highly likely that Cézanne was trying to express in the painting the sensation of riding in a train, a transportation method just emerging at the time (Fig. 10).

In fact in a letter to Emile Zola dated April 14, 1878, Cézanne praised Mont Sainte-Victoire, which he saw from the window of a train speeding along the Aix-en-Provence–Marseille line six months after it was opened, exclaiming, “What a beautiful motif.” Thereupon, Cezanne immediately began a series of paintings of Mont Sainte-Victoire, a motif he had not painted up to then at the age of 39. Something must have changed in his state of mind that led to his choice of such a hitherto radical subject for him. It would be natural to assume that the catalyst was, as he himself said, the aesthetic experience of seeing the scenery from a train window.

“I went to Marseille with [Joseph] Gibert. Those people know how to see; their eyes are teacher-like. When we passed by the Alexis’s House on a steam train, a dazzling motif unfolded in the east — Mont Sainte-Victoire and the rocky mountains towering above Beaurecueil. I said, “What a beautiful motif.” (1)

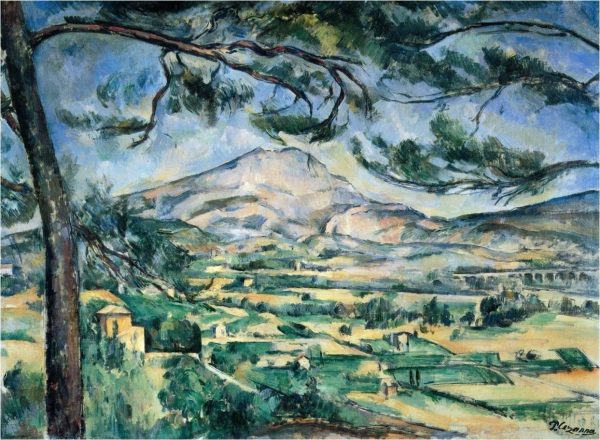

Interestingly, in the actual scenery seen from a train window, the distant Mont Sainte-Victoire moves slowly by, while the foliage in the foreground flashes by (Fig.11). This visual phenomenon is also a recognizable feature in many of Cézanne’s paintings (Fig.12). Moreover, the moment Cézanne said, “What a beautiful motif,” was just when his train was passing over a railway bridge, which is depicted in the Mont Sainte-Victoire series (Fig.13). Cézanne also included a train passing over a railway bridge in one of his paintings (Fig.14). It can thus be very likely said that Cézanne was acutely aware of this sense of contrasting speed.

Fig.11 Footage taken by author, Mont Sainte-Victoire seen while passing over the railway bridge in the valley of the Arc, August 26, 2006.

Fig.12 Paul Cézanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire with Large Pine, 1887.

Fig.13 Footage taken by author, Arc Valley railway bridge and Mont Sainte-Victoire, August 25, 2006.

Fig.14 Paul Cézanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Bellevue, 1882-85.

Still, it may be hard to believe that Cezanne depicted the visual perception of riding in a train. Especially since no one in the world has pointed to that possibility up to now.

However, we can surely believe Edgar Degas, when he himself said that he was inspired to paint landscapes after seeing the scenery from a train window (Fig.15, Fig.16). In fact, Degas said that in 1892 he painted 21 landscapes after he was inspired by the scenery he saw from a speeding train. Needless to say, Cézanne and Degas were old friends, and they were both Impressionists who were the first in France to seriously focus on steam locomotives in their art.

“(Those 21 landscape paintings) are the fruit of my travels this summer. Standing at the train door, I would gaze blankly at the scenery. That gave me the idea to paint landscapes.” (2)

Fig.15 Edgar Degas, Landscape, 1892.

Fig.16 Edgar Degas, Landscape, 1892.

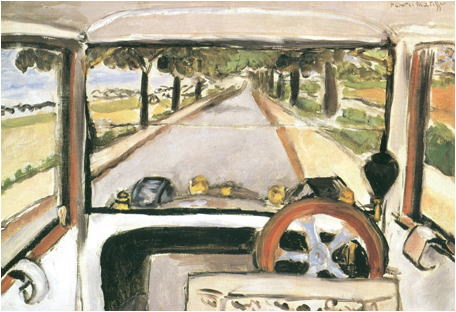

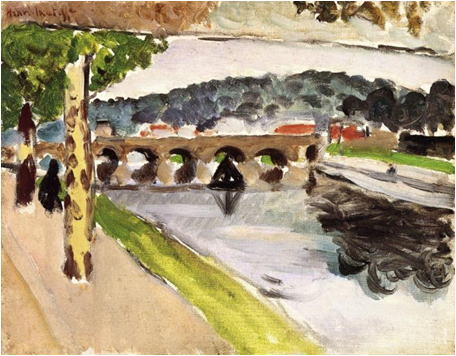

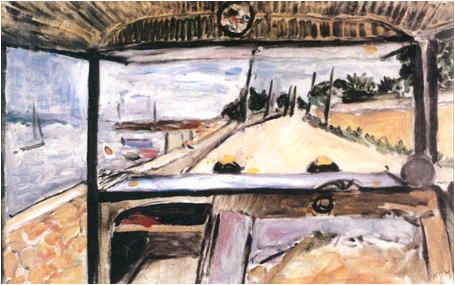

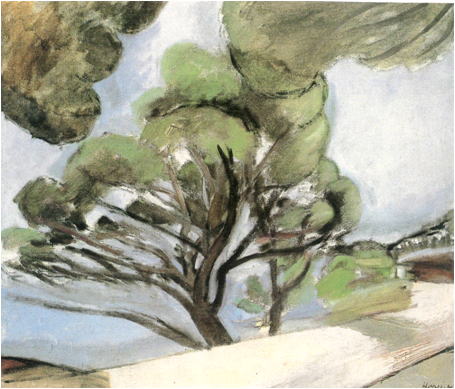

In addition, Fauvist Henri Matisse painted landscapes he had seen from the driver’s seat of a car. He also depicts landscapes as seen while driving a car (Fig.17–Fig.20).

Fig.17 Henri Matisse, The Windshield, 1917.

Fig.18 Henri Matisse, Sevres Bridge with Plane Trees, 1917.

Fig.19 Henri Matisse, Antibes, View from Inside an Automobile, 1925.

Fig.20 Henri Matisse, Road in Cap d’Antibes (The Large Pine), 1926.

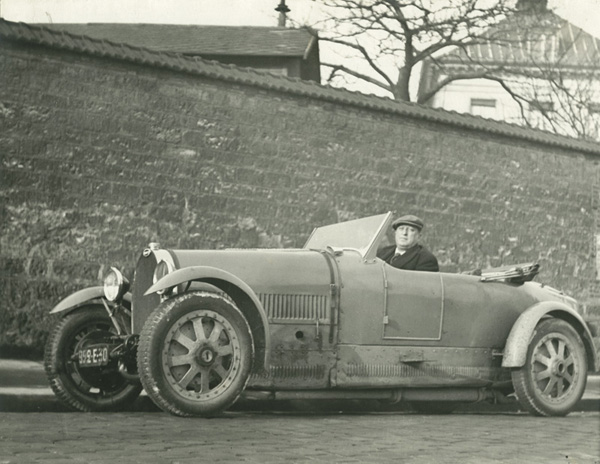

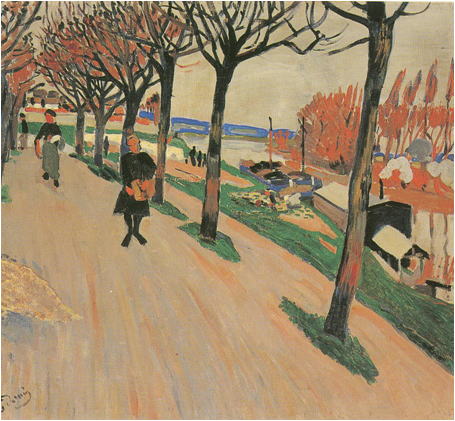

And then André Derain and Maurice de Vlaminck, both key figures in the Fauve movement who also loved cars, painted landscapes that looked as if they were painted from the driver’s seat of a speeding car (Fig.21–Fig.24). Not limited to painting, Vlaminck also described the visual sensations he experienced while driving cars at high speed in his autobiographical novel Dangerous Corner (1929).

“The headlights were searching the road. These two long, bright paintbrushes moved smoothly, limning the meandering and undulating ground. The pulsing of the eight-cylinder engine was even, smooth, and quiet, with almost no noticeable vibrations. The trees looked as if they were about to throw themselves in front of the car, and the wind made a soft scraping sound as it passed. I was pushing the racing car to about 110 kilometers an hour. A rabbit’s eyes, illuminated by the headlights, looked like the lights of an old-fashioned bicycle being peddled through the darkness. The road is at one moment one long white strip, and then at another it turns into a black snake, continuing on endlessly. It appears to be devoured by the hood of the car and then suddenly appears behind it. (3)

Fig.21 Photograph by Man Ray, André Derain in His Car, 1927.

Fig.22 André Derain, The Seine at Le Pecq, 1904.

Fig.23 Photographer unknown, Maurice de Vlaminck and His Car, circa 1926.

Fig.24 Maurice de Vlaminck, The Logny Road, 1953.

Of course, Cézanne, Degas, Matisse, Derain, Vlaminck, and Marie did not paint the scenery exactly the way they saw it while riding on a train or in an automobile, or while they were actually riding them. Rather the important point is that they were attempting to express the transformation of the visual sensation they felt as an everyday experience after getting off a high-speed moving vehicle. In other words, they were reconciling themselves to the new modern technological environment enveloping them and, in a symbolic way, trying to adopt it. That is precisely why their paintings have a definite artistic value for us who live in the same era.

That being the case, Marie can be said to be expressing the high-speed living environment of the 21st century during which trains and automobiles have become far more advanced than those of the late 19th to the early 20th centuries, when they influenced Impressionism and Fauvism, and airplanes have become utterly commonplace. In that sense, Marie can be described as the direct and latest successor to the “painters of modern life,” who, led by Cézanne, represented the transformation of the visual sense brought on by high-speed mechanical modes of transportation.

Notes

- Paul Cézanne, Correspondance, recueillie, annotée et préfacée par John Rewald, Paris, 1937; Nouvelle édition révisée et augmentée, Paris, 1978, p. 165. Japanese edition, John Rewald, ed., Sezan’nu no Tegami, Translated by Chuji Ikegami, Bijutsu Koronsha, 1982, pp.122-123.

- Edgar Degas, Lettres de Degas, recueillies et annotées par Marcel Guérin, Paris, 1931; nouvelle édition, Paris, 1945, pp. 277-278.

- Maurice de Vlaminck, Tournant dangereux: Souvenirs de ma vie, Paris, 1929, p. 262. Japanese edition, Vuramanku Abunai Magari-kado, Translated by Tokushi Saisho, Tokyo Kensetsu-sha, 1931, p.278.

*This article was commissioned by The Obsession Gallery for the Marie Rauzy Solo Exhibition, scheduled to run from January 14 to February 2, 2025.

(English translated by John Tamura)

【Related Posts】

■ Tomoki Akimaru, Cézanne and the Railway (1) – (7): A Transformation of Vision in the 19th Century.

Cézanne and the Railway (1): A Hidden Origin of Modern Vision

Cézanne and the Railway (2): The Earliest Railway Painting Among French Impressionists

Cézanne and the Railway (3): His Railway Subject in Aix-en-Provence

Cézanne and the Railway (4): His Railway Subject in Médan, Pontoise, Gardanne, and L’Estaque

Cézanne and the Railway (5): A Stylistic Analysis of His Pictorial Form

Cézanne and the Railway (6): The Influence of the Machine on the Shift from Subject to Form

Cézanne and the Railway (7): What is the Realization of Sensations?

■ Tomoki Akimaru, Fauvism and the Automobile: A Transformation of Vision in the 20th Century.