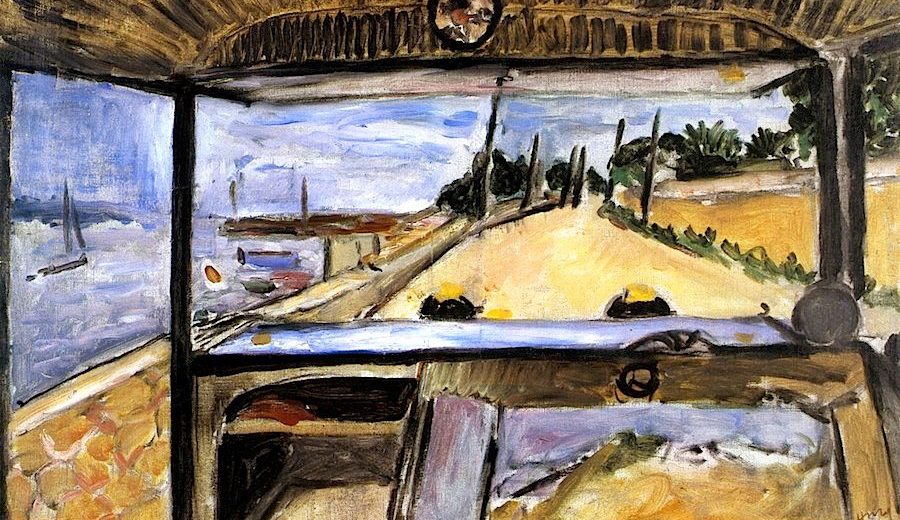

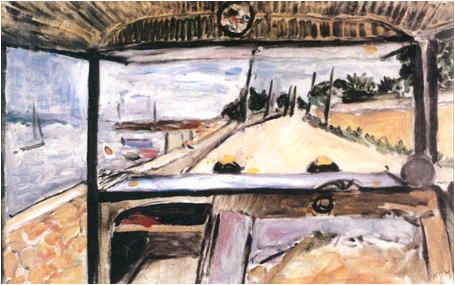

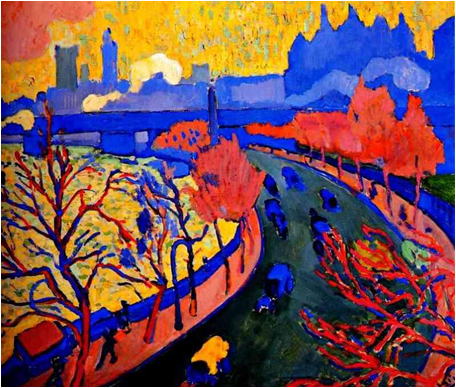

Fig. 1 Henri Matisse, The Windshield, 1917

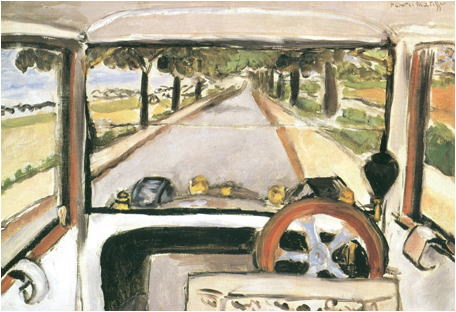

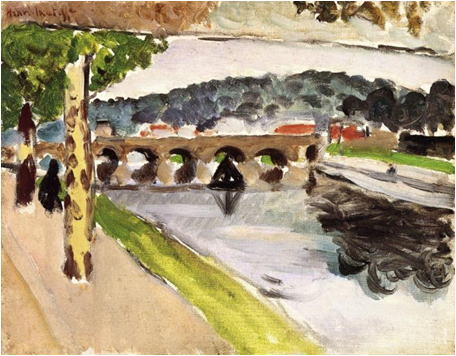

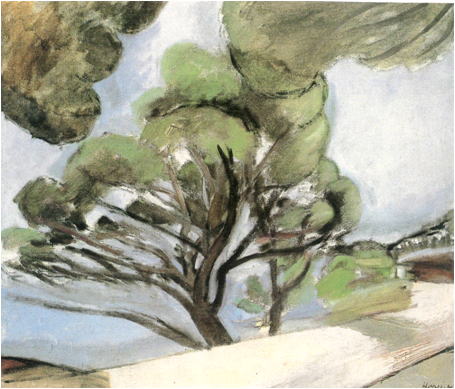

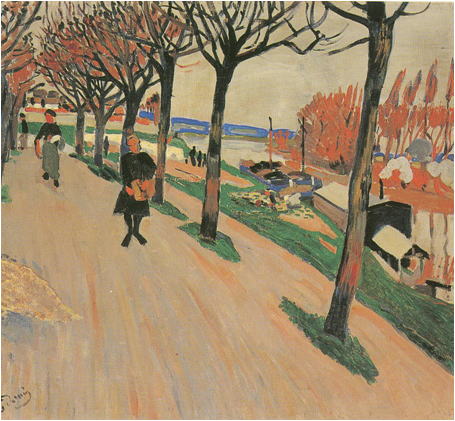

Fig. 2 Henri Matisse, The Bridge of Sèvres with Plane Trees, 1917

Fauvism was influenced by the automobile.

If you look through the window of a moving car, images that are closer appear rougher. Your tactile perception declines while you momentarily glance at objects passing by. In an interview with Léon Degand, Henri Matisse (1869-1954) stated the following regarding visual perception:

By car, one should not drive faster than 5 kilometers per hour. Otherwise, one doesn’t feel (making a feeling gesture with his hand) the trees anymore.

Louis Aragon has argued that Matisse’s painting titled The Windshield (1917) (Fig. 1) was the first painting to depict the world as seen from the inside of a car. Matisse also created a series of paintings depicting scenes viewed from the driver’s seat (Fig. 2-Fig. 4).

Fig. 3 Henri Matisse, Antibes, View from Inside an Automobile, 1925

Fig. 4 Henri Matisse, Road in Cap d’Antibes (The Large Pine), 1926

Driving a car at high speed will stimulate your aggressive instinct; it will make you behave like a wild beast.

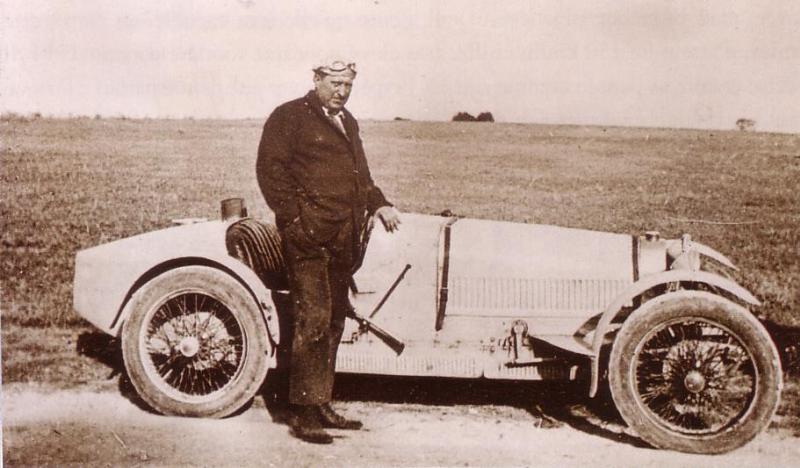

A number of art critics, such as Jean Cassou and René Huyghe, contend that Maurice de Vlaminck (1876-1958) (Fig. 4) was influenced by the images he witnessed while driving a car at high speed. Indeed, Vlaminck vigorously painted many turbulent landscapes, giving the impression he was infatuated with speed (Fig. 6-Fig. 7). Moreover, he described the following scene as witnessed from an accelerating car in his novel titled Dangerous Corner in 1929:

The headlights probed the roads like two long luminous paint brushes; they moved gently, picking out swelling hill-sides and valleys. The throb of the eight cylinders was scarcely noticeable, so sweet, even and silent was the engine. The trees seemed about to cast themselves down on to the bonnet of the car, and as we swept by, they rustled in our draught. The racing “torpedo” ran at 110 kilometers per hour. The eyes of rabbits, lit by the beam of the headlight, were like the lamps of belated cyclists pedaling through the dark. The road now became an immense white ribbon, now a black snake, stretching into infinity. It seemed to be devoured by the bonnet of the car and swept suddenly behind.

Fig. 4 Maurice de Vlaminck and his automobile

Fig. 5 Maurice de Vlaminck, The Mortagne Road, 1953

Fig. 6 Maurice de Vlaminck, The Logny Road, 1953

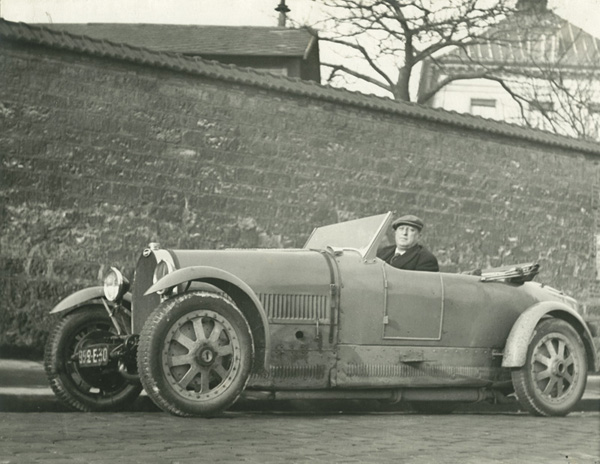

In addition, André Derain (1880-1954) drove a number of Bugattis; one of them had a top speed of 240 kilometers per hour (Fig. 7-Fig. 10). He told Foujita Tsuguharu that it is pleasant to drive a car at high speed. A car that does not run at high speed cannot be called a car.

In fact, Derain painted Charing Cross Bridge (1906) (Fig. 11), a painting that depicts speeding motor vehicles. He also painted The Seine at Pecq (1904) (Fig. 12), which seems like an image observed from the driver’s seat of a speeding car.

Fig. 7-Fig. 10 André Derain and his automobile

Fig. 11 André Derain, Charing Cross Bridge, 1906

Fig. 12 André Derain, The Seine at Pecq, 1904

These three fauvists were familiar with images flashing through the windows of a speeding car. It is undeniable that the fleeting scenes from a speeding automobile coupled with increased aggressive instinct influenced the violent coloring of Fauvism.

【Related Posts】

■ Tomoki Akimaru, Cézanne and the Railway (1) – (7): A Transformation of Visual Perception in the 19th Century.

Cézanne and the Railway (1): The Hidden Origin of Modern Vision

Cézanne and the Railway (2): The Earliest Railway Painting Among French Impressionists

Cézanne and the Railway (3): His Railway Subject in Aix-en-Provence

Cézanne and the Railway (4): His Railway Subject in Médan, Pontoise, Gardanne, and L’Estaque

Cézanne and the Railway (5): A Stylistic Analysis of His Pictorial Form

Cézanne and the Railway (6): The Influence of the Machine on the Shift from Subject to Form

Cézanne and the Railway (7): What is the Realization of Sensations?

● Marie Rauzy — A contemporary French painter descended from Paul Cézanne