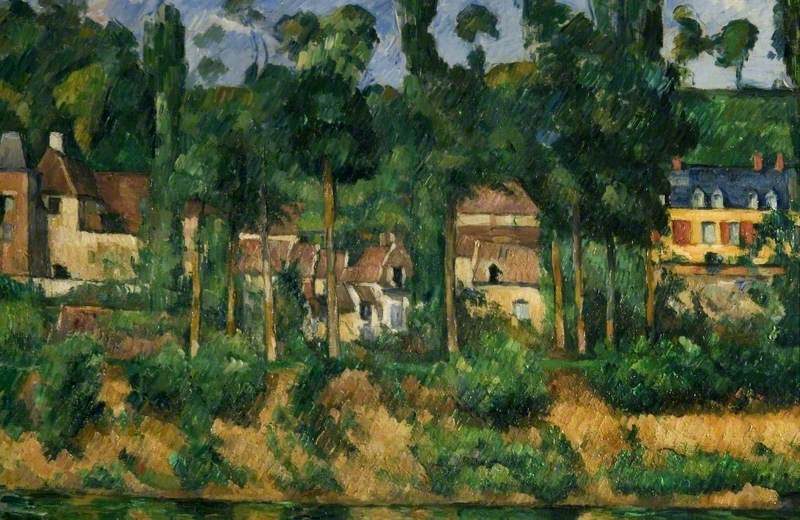

Fig. 1 Paul Cézanne, The Catsle of Médan, c. 1879.

In Section 2, we saw that Paul Cézanne (1839-1906) painted a railway station in The Ferry at Bonnières (1866), and was the earliest to topicalize the railway among French Impressionist painters.

And in Section 3, we saw that Cézanne daily used not only steam trains but also electric trains from his youth to his later years in his hometown of Aix-en-Provence. Correspondingly, from the beginning to the end of his career, he produced a large number of paintings of various railway subjects in Aix-en-Provence, including cuttings, signals, tracks, bridges, and locomotives.

In addition, in other areas Cézanne often rode trains and painted the railways as a subject. In this section, we will research his railway subjects in Médan, Pontoise, Gardanne, and L’Estaque.

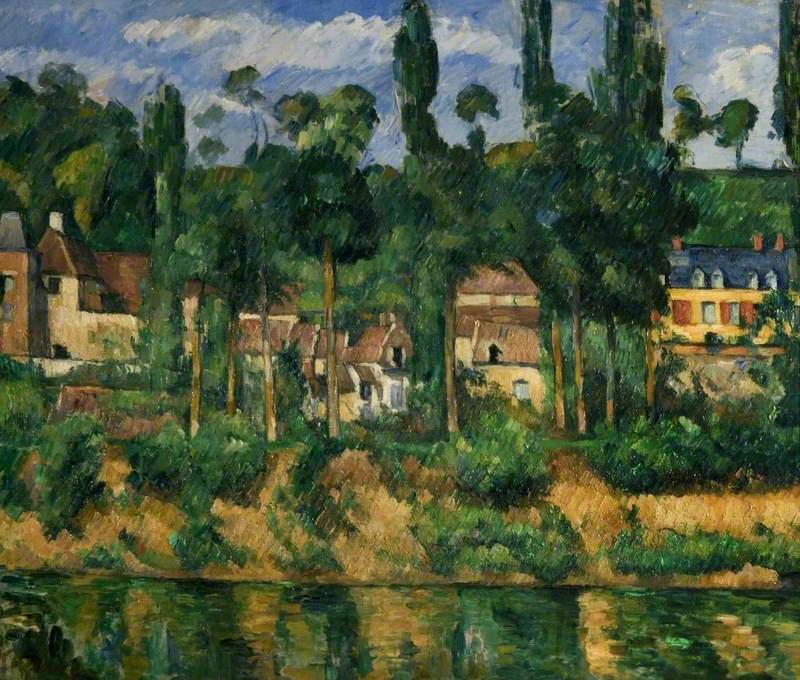

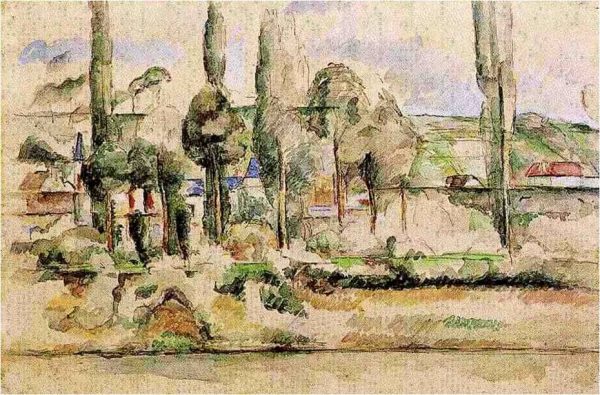

Fig. 2 Paul Cézanne, The Catsle of Médan, c. 1879.

Fig. 3 A photograph of the scene in Fig. 1 and Fig. 2

photographed by Émile Zola

in the late 19th century.

Fig. 4 A photograph of the Paris-Le Havre line in front of Zola’s house

photographed by Émile Zola

in the late 19th century.

Fig. 5 A photograph of a railway train seen from Zola’s mansion

photographed by Émile Zola

in the late 19th century.

Fig. 6 A photograph of a railway train seen from Zola’s mansion

photographed by Émile Zola

in the late 19th century.

Fig. 7 A self-portrait

photographed by Émile Zola

in the late 19th century.

First, Cézanne painted the landscape along the railway line in Médan, a farming village about 25 kilometers from Paris. In fact, the railway is hidden in his oil painting The Castle of Médan (c. 1879) (Fig. 1) and watercolor The Castle of Médan (c. 1879) (Fig. 2).

These two paintings are believed to be created in 1879, when Cézanne visited the castle-like mansion that his close friend Émile Zola had purchased in Médan. Interestingly, Zola, a well-known train enthusiast and amateur photographer, from his mansion which faced the railway tracks of the Paris-Le Havre line, photographed the steam locomotives passing by (Fig.3-Fig. 7).

After this visit, Cézanne wrote to Zola on June 23, 1879, noting that he waved to Zola from the moving train as he approached his friend’s mansion. Zola must have looked at the train just like the photos above (Fig. 5 and Fig. 6).

I arrived without any catastrophe at the station at Triel and my arm, waved across the door as I passed in front of your castle, must have revealed to you my presence in in the train―which I didn’t miss (1).

From these facts, these two paintings, although they appear to be a simple natural scenery at first glance, are actually an artificial scenery with steam locomotives passing horizontally through the center of the picture. In other words, the nature represented by trees, bank, and river is secretly contrasted with the train, which embodies modernity despite its absence.

Fig. 8 Paul Cézanne, The Bridge and Waterfall at Pontoise, 1881.

Fig. 9 A photograph of the scene in Fig. 8.

(photographer and date unknown)

Second, Cézanne painted a railway bridge in Pontoise, a country town about 30 kilometers from Paris. In fact, in The Bridge and Waterfall at Pontoise (1881) (Fig. 8), a railway bridge on the Paris-Lille line is visible and hidden.

In this painting, Cézanne depicts the Oise River as a natural object, and the bridge and weir as man-made structures. The artificial straight lines of the bridge and the weir contrast with the natural curves of the surrounding trees and plants. In short, Cézanne is contrasting nature and artifice.

Furthermore, as can be confirmed in the photograph of the actual site (Fig. 9), this bridge is a combination of a pedestrian bridge and a railway bridge. In other words, Cézanne contrasts nature and modernity in terms of means of transportation. Therefore, in this work, the invisible train passing horizontally through the center of the picture and the various natural elements surrounding it secretly contrast nature and artifice in multiple layers.

Moreover, a letter to Camille Pissarro, dated December 11, 1872, indicates that Cézanne used the train to travel between Pontoise and Auvers-sur-Oise, where he lived at the time.

I take up Lucien’s pen at a time when the train should have been taking me to my Penates. I am telling you in a round-about way that I have missed my train (2).

Fig. 10 Paul Cézanne, Gardanne, Old Bridge, 1885-86.

Fig. 11 A photograph of the scene in Fig. 10

photographed by Erle Loran

in the late 1920s.

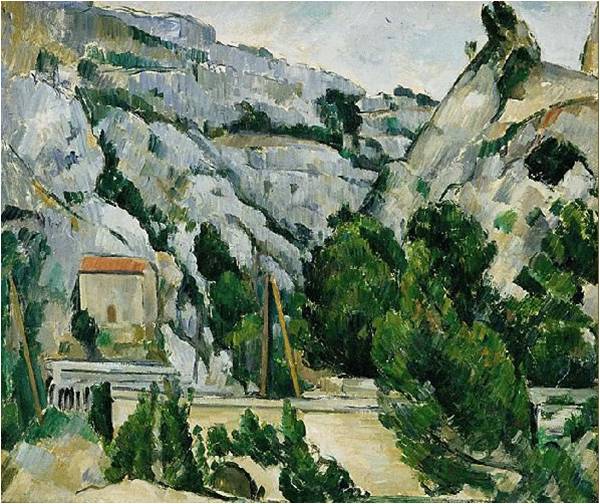

Third, Cézanne also painted a railway bridge in Gardanne, a neighboring town about 10 kilometers from Aix-en-Provence. In fact, despite the subtitle “Old Bridge” in Gardanne, Old Bridge (1885-86) (Fig. 10), as can be seen from the site photo (Fig. 11), he depicts the railway bridge on the Aix-Marseille line.

Like this, Cézanne’s railway paintings are difficult to recognize at first glance as depicting a railway-related subject, not only from the painting itself but also from the titles. In this case, rather than focusing on the railway bridge, the picture contrasts nature and modernity by juxtaposing the railway bridge with the surrounding trees.

At the time this work was painted, Cézanne frequently visited Gardanne. For example, in a letter to Émile Zola dated August 20, 1885, he told, “I am at Aix and I go to Gardanne every day (3),” and in a letter to Émile Zola dated August 25, 1885, he wrote, “I go to Gardanne every day and in the evening I come back to the country Aix (4).” Considering the time and distance, there is no doubt that Cézanne used the Aix-Marseille line to travel from Aix to Gardanne.

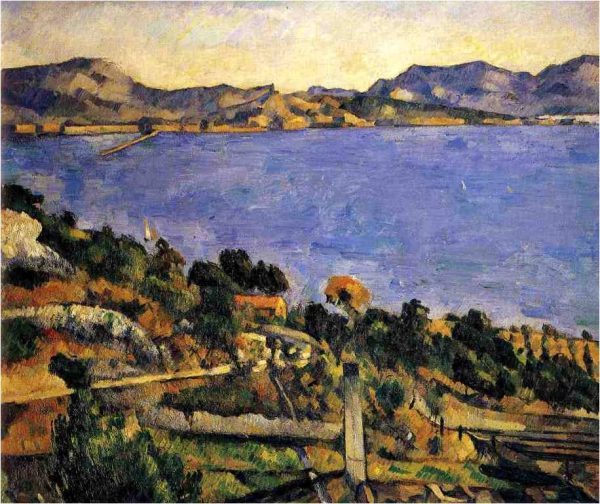

Fig. 12 Paul Cézanne, The Bay of Marseille seen from L’Estaque, 1878-79.

Fig. 13 A photograph of the scene in Fig. 12

(date unknown)

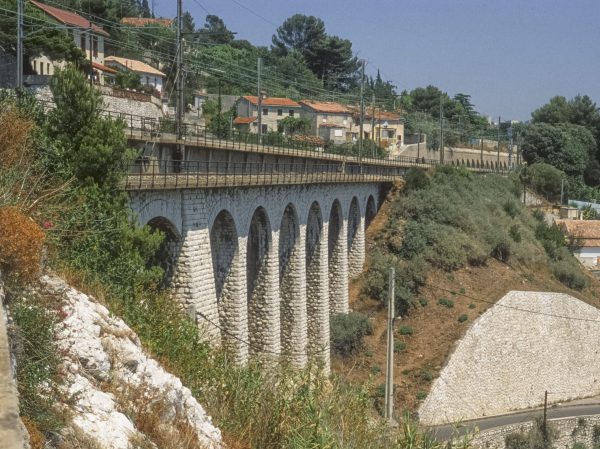

Fig. 14 A railway bridge at L’Estaque

photographed by Ignis

in 2006.

And, Cézanne also painted railway scenes at L’Estaque. In fact, it can be seen from the on-site photograph that two of the parallel black lines in the lower right of The Bay of Marseille seen from L’Estaque (1878-79) (Fig. 12) are railway tracks that run through L’Estaque (Fig. 13).

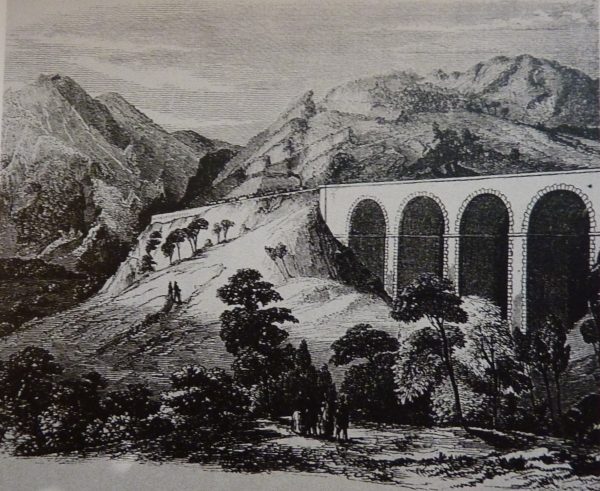

In addition, railway tracks run along the coast of the Bay of Marseille, and there are many railway bridges around L’Estaque (Fig. 14). Cézanne also painted such railway bridge in The Viaduct at L’Estaque (1879-82) (Fig. 15) and The Viaduct at L’Estaque (1882) (Fig. 18).

In these works, too, the railway subject is depicted not explicitly but implicitly, creating a contrast between the abundant nature and hidden modernity.

It is evident from a letter to Émile Zola dated May 24, 1883, that Cézanne’s daily life was closely connected with the steam railway, as he reported that he had rented a house close to the L’Estaque station.

I have rented a little house and garden at l’Estaque just above the station (5).

Fig. 15 Paul Cézanne, The Viaduct at L’Estaque, 1879-82.

Fig. 16 A photograph of the scene in Fig. 15

(date unknown)

Fig. 17 Paul Cézanne, L’Estaque, Melting Snow, circa 1871.

Fig. 18 Paul Cézanne, The Viaduct at L’Estaque, 1882.

Fig. 19 A photograph of the scene in Fig. 18

(date unknown)

Fig. 20 A photograph of the scene in Fig. 18

(date unknown)

As we have seen, a characteristic of Cezanne’s railway paintings is that to someone who has not actually seen the scene, it is unclear that the railway subject is depicted in the landscape. Furthermore, rather than focusing on the steam railway alone, they show a complex character that contrasts the idyllic nature with the modern era represented by the steam railway.

In terms of forms, although no one has pointed this out before, for example, in The Castles of Médan (Fig. 1) and The Castles of Médan (Fig. 2), the river, banks, and ridgelines that connect the left and right sides of the screen, as well as the brushstrokes that are repeated horizontally – so-called Cézanne’s unique “constructive strokes” – can be said to be influenced by the horizontal movement of the railway train.

Notes

(1) Paul Cézanne, Correspondance, recueillie, annotée et préfacée par John Rewald, Paris, 1937; nouvelle édition révisée et augmentée, Paris, 1978; English translated by Marguerite Kay, New York, 1941; new edition revised and enlarged, New York, 1976; First Da Capo Press edition, New York, 1995, p. 180.

(2) Ibid., p. 136.

(3) Ibid., p. 220.

(4) Ibid., p. 221.

(5) Ibid., p. 209.

Fig. 3-Fig. 7 were quated from Emile Zola, Photograph, Eine Autobiographie in 480 Bildern, herausgegeben und zusammengestellt von François-Emile Zola und Massin, München: Schirmer/Mosel, 1979.

Fig. 9 was quated from Joachim Pissarro et Claire Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: catalogue critique des peintures, critical catalogue of paintings, tome II, Paris: Skira, 2005.

Fig. 11 was quated from John Rewald, Paul Cézanne: The Watercolors, A Catalogue Raisonné, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1983.

Fig. 13 was quated from Google Street View.

Fig. 14 was quated from Wikipedia (BB-67400 Estaque Marseille FRA 001 – Marseille – Wikipedia)

Fig. 16, Fig. 19, and Fig. 20 were quated from La Société Paul Cezanne.

【Related Posts】

■ Tomoki Akimaru, Cézanne and the Railway (1) – (7): A Transformation of Vision in the 19th Century.

Cézanne and the Railway (1): A Hidden Origin of Modern Vision

Cézanne and the Railway (2): The Earliest Railway Painting Among French Impressionists

Cézanne and the Railway (3): His Railway Subject in Aix-en-Provence

Cézanne and the Railway (4): His Railway Subject in Médan, Pontoise, Gardanne, and L’Estaque

Cézanne and the Railway (5): A Stylistic Analysis of His Pictorial Form

Cézanne and the Railway (6): The Influence of the Machine on the Shift from Subject to Form

Cézanne and the Railway (7): What is the Realization of Sensations?

■ Tomoki Akimaru, Fauvism and the Automobile: A Transformation of Vision in the 20th Century.

● Marie Rauzy — A contemporary French painter descended from Paul Cézanne