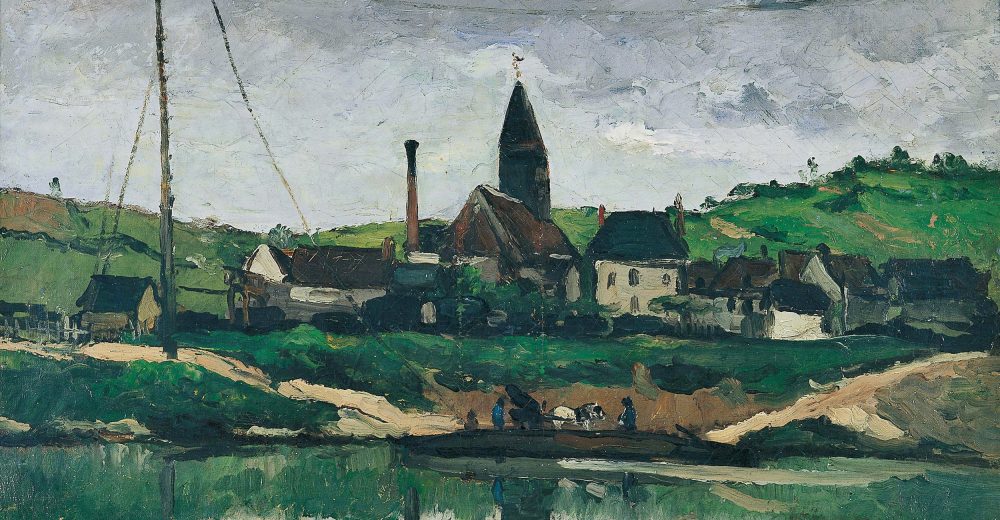

Fig. 1 Paul Cézanne The Ferry at Bonnières summer of 1866

Paul Cézanne is the first painter to depict the railway among Impressionist painters (Fig. 1).

In France, the Impressionists were the first to zealously portray the railway. It has been said that A Landscape at Pâtis, Pontoise (1868) (Fig. 2) painted by Camille Pissarro (1830-1903) or A Train in the Country (1870) (Fig. 3) executed by Claude Monet (1840-1926) is the earliest railway painting among the works of the French Impressionists.

Actually, it is Cézanne who was the first to depict the railway. This is important because it means that he was the most sensitive artist to “modernité (modernity)” which Charles Baudelaire extolled as a highly desirable quality of avant-garde artists.

Fig. 2 Camille Pissarro A Landscape at Pâtis, Pontoise 1868

Fig. 2

Fig. 3 Claude Monet A Train in the Country 1870

In France in the 1870s, it was unconventional to draw the steam locomotive because it was labeled an ugly monster that surged forward at an extraordinary speed, complete with deafening roars. Similarly, railroads were considered unwelcome intruders upon natural landscapes.

Therefore, painters avoided painting scenery which showed the railway prominently. If a train was depicted, it was usually drawn small and from a distance in a drawing or a print. Trains were seldom featured in oil paintings.

Under such circumstances, members of the Impressionist group led by Pissarro and Monet were considered innovators in the sense that they were the first artists in France to topicalize the railway in oil paintings. (Here, I would like to point out that in Pissarro’s painting (Fig. 2), the steam locomotive is hardly noticeable, and in Monet’s painting (Fig. 3), the train is hidden behind trees.)

Interestingly, Cézanne, a painter of modern life as well as a well-known lover of nature, topicalized the railway before Pissarro and Monet did. In fact, Cézanne painted The Ferry at Bonnières (Fig. 1) in the summer of 1866.

If one actually stands at the spot from which the scene is viewed, one will notice that the Bonnières station on the Paris to Le Havre line is near the telegraph pole, which is depicted on the left side of this painting, and the train passes from the right to the left (Fig. 4-Fig. 9).

Cézanne sketched from this very spot. In The Ferry at Bonnières, he discreetly depicted not only the ferry but also the railway station, that is, he expressed the contrast between modern and pre-modern life. (I believe that at the time, Cézanne was still hesitant to paint the steam locomotive itself.)

In addition, according to Wolfgang Schivelbusch’s The Railway Journey (1977), in the 19th century, the telegraph network developed along with the railway network to facilitate the smooth operation of the train system[1]. When the Bonnières station was established on May 9, 1843, the telegraph pole and electric wires, which Cézanne drew, were definitely part of the railway system. Cézanne depicted two railway subjects, being a station, and a telegraph pole and electric wires.

Fig. 4 A train passing through Bonnières station

(Filmed by the author on August 28, 2006)

Fig. 5 A train leaving Bonnières station

(Filmed by the author on August 28, 2006)

Fig. 6

Fig. 7

Fig. 8

Fig. 9

Fig. 4-Fig. 9 The scenery around Bonnières station

(Photographed by the author on August 28, 2006)

It is very important to note that novelist Émile Zola, who was Cézanne’s best friend since junior high school, mentioned “the railway and the telegraph” three times in My Hatreds (1866) published just before Cézanne’s first railway painting (Fig. 1).

Actually, Zola said in the preface: “We are in an age in which, through the railway and the telegraph, we can transport our bodies and thoughts absolutely and infinitely, and in which the human mind suffers tremendous pain and is serious and restless.[2]”

In “Literature and Gymnastics,” Zola wrote: “We are in an age in which the railway often elicits uneasy bitter smiles like those elicited by a bad comedy, and in which, the telegraph, in the most extreme cases, conveys merciless realities.[3]”

Moreover, in “Mr. H. Taine, Artist” Zola insisted: “I believe that the new scientific method of critiquing literature and art is contemporaneous with the telegraph and the railway.[4]”

By these references to “the railway and the telegraph,” Zola objected to the obsolete aesthetic sense of the older generations, who sought to escape from the realities that were developing rapidly in quest of their idealized notions of beauty.

In fact, Zola, in Claude’s Confession (1865) that was dedicated to “my friend P. Cézanne,[5]” proclaimed: “No more lies! The brutal truth is strangely sweet for those who are tormented by the problems of life.[6]”

In Two Definitions of the Novel (1866), Zola explained that “the novel method of observation and analysis” was produced under the “scientific and mathematical tendency of modern times.[7]”

Furthermore, in My Hatreds (1866), Zola discussed the new trend of “scientific” study in literature and argued: “Modern society is here and is waiting for the historians,[8]” and, in My Salon (1866), which he dedicated to “my friend Paul Cézanne,[9]” Zola reiterated that in the “scientific” trend of the times, “To paint dreams is child’s and woman’s play; men have to paint realities.[10]”

Later, Zola commented in “Téophile Gautier” (1879) that “Romanticists abominated the spirit of the century. They abhorred the great scientific and industrial movement. According to them, the railway and the telegraph ruined the best of sceneries.[11]”

In his letter to Camille Pissarro dated March 15, 1865, Cézanne said that he intended to send his aggressive painting to the official Salon that did not accept its new aesthetic sense and “make the Institute blush with rage and despair.[12]”

Then, Cézanne enjoyed a vacation with Zola around Bonnières in the summer of 1866 and painted The Ferry at Bonnières during that period; Zola owned the painting until his death.

The Ferry at Bonnières was a bold declaration that young Cézanne would fight with Zola against the conservative older generations. Undoubtedly, Cézanne and Zola, who were aware of the actual spot, understood that this picture topicalized the railway. It is certain that as a mark of his close friendship with Zola, Cézanne included in the painting “the railway and the telegraph,” which were loathed by the older generations.

More interestingly, in The Masterpiece (1886) in which the main character is modeled on Cézanne, Zola wrote about a train trip from Paris to Bonnières as being a trendy new diversion and described the exact same place that is depicted in The Ferry at Bonnières (Fig. 1).

Claude was delighted to have her with him for a whole day and suggested taking her to the country, feeling he wanted her all to himself, far away from everything, in the sunshine. Christine was thrilled by the idea, so they rushed out like a pair of mad things and reached the Saint-Lazare Station just in time to jump into the train for Le Havre. He knew a small village just on the other side of Mantes, Bennecourt, where there was an artists’ inn on which he had descended more than once with his friends, and, without a thought for the two-hour journey, he took her there for lunch with as little fuss as if he had been taking her no farther afield than Asnières. She thought the long journey was great fun; the longer the better! It seemed impossible that the day itself could ever come to an end. By ten o’clock they were at Bonnières. There they took the ramshackle old ferry boat, worked by a chain, across the Seine to Bennecourt.[13]

Therefore, it is my belief that The Ferry at Bonnières (Fig. 1), which depicts the same place as this text describes, expresses the same feeling of freedom inspired by the high-speed train (Fig. 10-Fig. 12). To conclude, The Ferry at Bonnières painted by Cézanne in the summer of 1866 is the earliest railway painting among the works of the French Impressionists.

Fig. 10 A Train Window Scenery from Saint-Lazare Station to Bonnières Station.

(Filmed by Tomoki Akimaru on August 28, 2006)

Fig. 11 The ferry and the station at Bonnières

(Photographed by the author on August 28, 2006)

Fig. 12 The scenery around Bonnières Station and the Seine River

(Photographed by the author on August 28, 2006)

[1] Wolfgang Schivelbusch, The Railway Journey: The Industrialization of Time and Space in the 19th Century, Berkeley and Los Angeles: The University of California Press, 1986, pp. 29-32.

[2] Émile Zola, Mes Haines (1866), in Œuvres complètes, tome I, Paris: Nouveau Monde, 2002, p. 723.

[3] Ibid., p. 750.

[4] Ibid., p. 835.

[5] Émile Zola, La Confession de Claude (1865), in Œuvres complètes, tome I, Paris: Nouveau Monde, 2002, p. 407.

[6] Ibid., p. 439.

[7] Émile Zola, Deux définitions du roman (1866), in Œuvres complètes, tome II, Paris: Nouveau Monde, 2002, p. 510.

[8] Émile Zola, Mes Haines (1866), in Œuvres complètes, tome I, Paris: Nouveau Monde, 2002, p. 820.

[9] Émile Zola, Mon Salon (1866), in Œuvres complètes, tome II, Paris: Nouveau Monde, 2002, p. 617.

[10] Ibid., p. 642.

[11] Paul Cezanne, Letters, edited by John Rewald, translated from the French by Marguerite Kay, New York: Da Capo Press, 1995, p. 102. (cf. Paul Cézanne, Correspondance, recueillie, annotée et préfacée par John Rewald, Paris: Bernard Grasset, 1937; nouvelle édition révisée et augmentée, Paris: Bernard Grasset, 1978, p. 113.)

[12] Émile Zola, “Téophile Gautier” (1879), in Œuvres complètes, tome X, Paris: Nouveau Monde, 2004, p. 710.

[13] Émile Zola, The Masterpiece, translated by Thomas Walton, translation revised and introduced by Roger Pearson, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999, pp. 155-156.

【Related Posts】

■ Tomoki Akimaru, Cézanne and the Railway (1) – (7): A Transformation of Vision in the 19th Century.

Cézanne and the Railway (1): A Hidden Origin of Modern Vision

Cézanne and the Railway (2): The Earliest Railway Painting Among French Impressionists

Cézanne and the Railway (3): His Railway Subject in Aix-en-Provence

Cézanne and the Railway (4): His Railway Subject in Médan, Pontoise, Gardanne, and L’Estaque

Cézanne and the Railway (5): A Stylistic Analysis of His Pictorial Form

Cézanne and the Railway (6): The Influence of the Machine on the Shift from Subject to Form

Cézanne and the Railway (7): What is the Realization of Sensations?

■ Tomoki Akimaru, Fauvism and the Automobile: A Transformation of Vision in the 20th Century.

● Marie Rauzy — A contemporary French painter descended from Paul Cézanne