The Museum Yamato Bunkakan

Special Exhibition: “Blowing in the Wind — Expressions of Weather in East Asian Art”

Period: May 30 (Fri) – July 6 (Sun), 2025

Venue: The Museum Yamato Bunkakan

The exhibition “Blowing in the Wind — Expressions of Weather in East Asian Art” is currently on view at the Museum Yamato Bunkakan. Located in a quiet residential area near Gakuenmae Station on the Kintetsu Nara Line, which connects Osaka and Nara, the museum stands within a vast garden. The modernist building, designed by Yoshida Isoya — a master of modern sukiya architecture — features Japanese-inspired elements such as namako walls and mushiko-mado lattice windows. While the exhibition space consists of a single floor, it always presents valuable works from its collection. The museum was founded by Taneida Torao, then president of Kintetsu Railway, who invited the internationally renowned art historian Yashiro Yukio to be its first director. Under Yashiro’s guidance, the museum systematically assembled a collection of East Asian art.

Those familiar with East Asian art or modern architecture may already know this museum, but it is not widely recognized among the general public. Personally, however, it is one of my favorite museums. If an “art festival” is, as its name implies, a temporary and extraordinary event tied to specific times and places, then a museum should be a place of spiritual calm within everyday life. Unlike exhibitions that aim to draw massive crowds, this museum offers a place to soothe the soul through seasonal flowers in the garden and its exhibitions — making it uniquely suitable for such an experience.

In recent years, I have been contemplating the concept of “meteorological art.” This is not unrelated to the fact that “climate change” is threatening our daily lives on a global scale. More importantly, weather and climate are deeply connected to art in ways we might not readily realize. As the cognitive scientist Isamu Motoyoshi points out, the lighting environment shaped by climate and weather influences human perception and shapes the “visual brain.” In the Mediterranean climate where Western art developed, dry summers and strong sunlight create sharp shadows and a three-dimensional worldview. In contrast, in monsoon climates like Japan’s, high humidity and scattered sunlight create a more diffused light, fostering a planar worldview. These differences manifest in the distinct expressions and styles of Western and Eastern art. In other words, climate and weather significantly influence our perceptions and value judgments, which are the foundations of artistic expression.

Climate and weather affect not only the “visual brain” that perceives the world but also the external environment and artistic materials. In Japan, with its pronounced seasonal changes and rich vegetation, this is even more apparent. High humidity impacts materials such as ink, paper, and water, while also complicating conservation efforts. Art may be said to emerge from the interaction between external conditions and internal sensibilities. My concept of “meteorological art” asks whether we can reconsider art within such environmental contexts. This exhibition seemed like a fitting opportunity to explore that question.

The exhibition’s main theme is how weather has been depicted in East Asian ink painting, primarily using paper and ink. As the works share similar climates and materials, comparisons are easier to make. It explores how the monsoon climate that covers East Asia has influenced our environment, bodies, and culture, and how these influences have been reflected in artistic expression. The exhibition allows us to see stylistic changes across different regions — China, Korea, and Japan — and different eras.

However, ink painting was never fundamentally about realism. In Chinese aesthetics, literati painters were regarded more highly than professional painters, so concrete depictions of weather were not necessarily emphasized.

In East Asia, “weather” is understood as an expression of qi, the circulating energy of nature. Thus, it is not viewed as purely physical phenomena such as atmospheric conditions, rain, wind, or snow in the modern scientific sense. The Southern Qi art theorist Xie He listed “spirit resonance, life-motion” (qi yun sheng dong) as the first of his “Six Principles of Painting” in The Record of the Classification of Old Painters. This refers to the lively manifestation of qi, which is seen as essential in painting.

From this perspective, looking at “expressions of weather in East Asian art” purely through a Western, realistic lens — focusing on how rain, wind, or snow are depicted — risks missing the essence. Rather, the correct approach might be to see these works in terms of “qi yun sheng dong” as well as meteorological representation. At the same time, it remains valuable today to reexamine these works from a scientific, objective standpoint.

The decision to focus on “wind” among many weather phenomena is intriguing. The title “Blowing in the Wind” is widely known in Japan as the translation of Bob Dylan’s iconic song “Blowin’ in the Wind,” which greatly influenced the civil rights and anti-Vietnam War movements — though here, it has no direct connection to that context. Why, then, “Blowing in the Wind”? Perhaps because in ink paintings, not only landscapes but also figures, including the artist, often appear within the scene. The perspective is thus not a “first-person” view as seen by the artist, but rather a “third-person” view in which figures exist within the landscape, visibly “blown by the wind.”

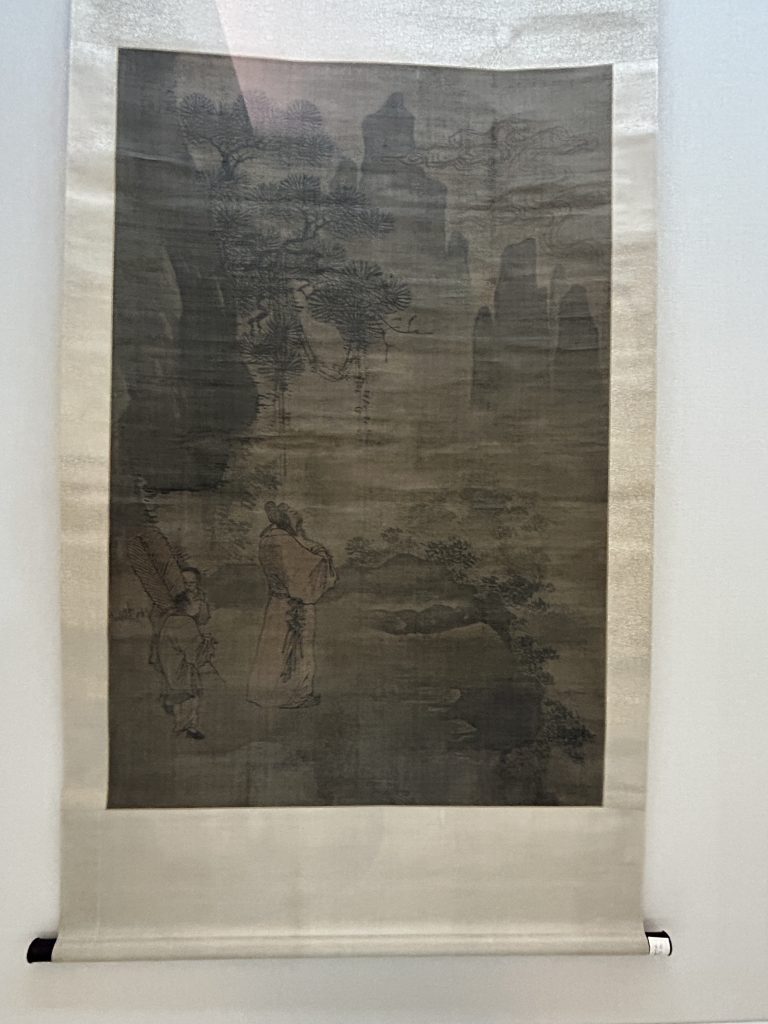

Zhang Lu, Wangqi Tu (Ming dynasty, China) Collection of The Museum Yamato Bunkakan

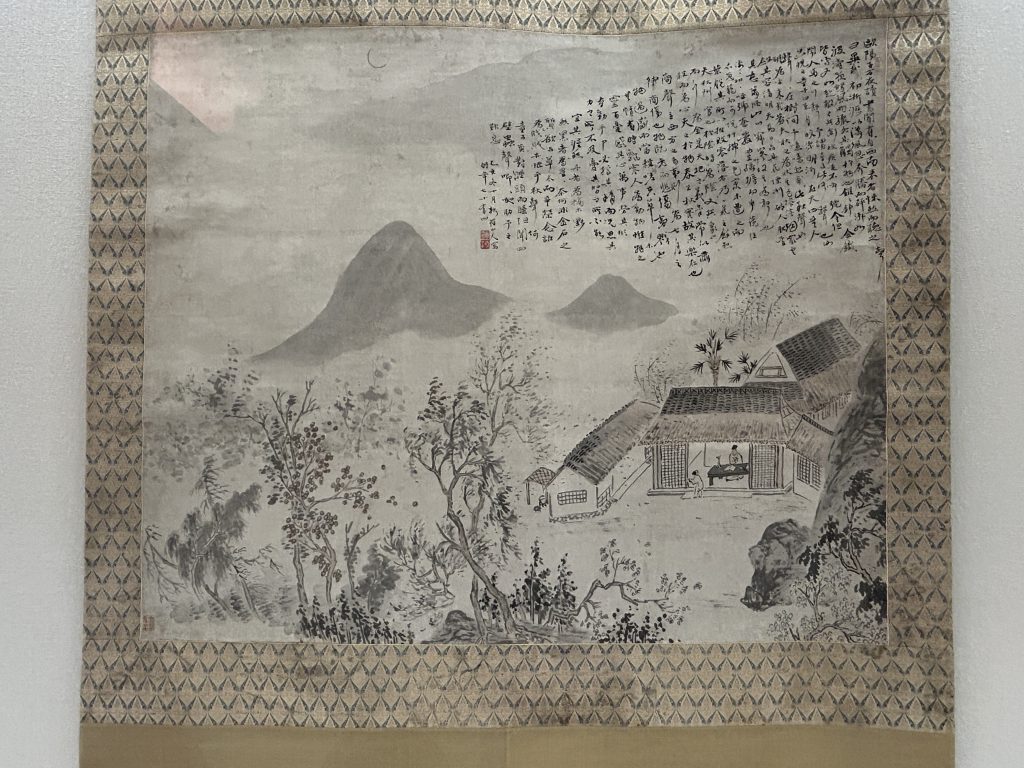

Hua Yan, Qiusheng Fuyi Tu (1755, Qing dynasty) Collection of Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

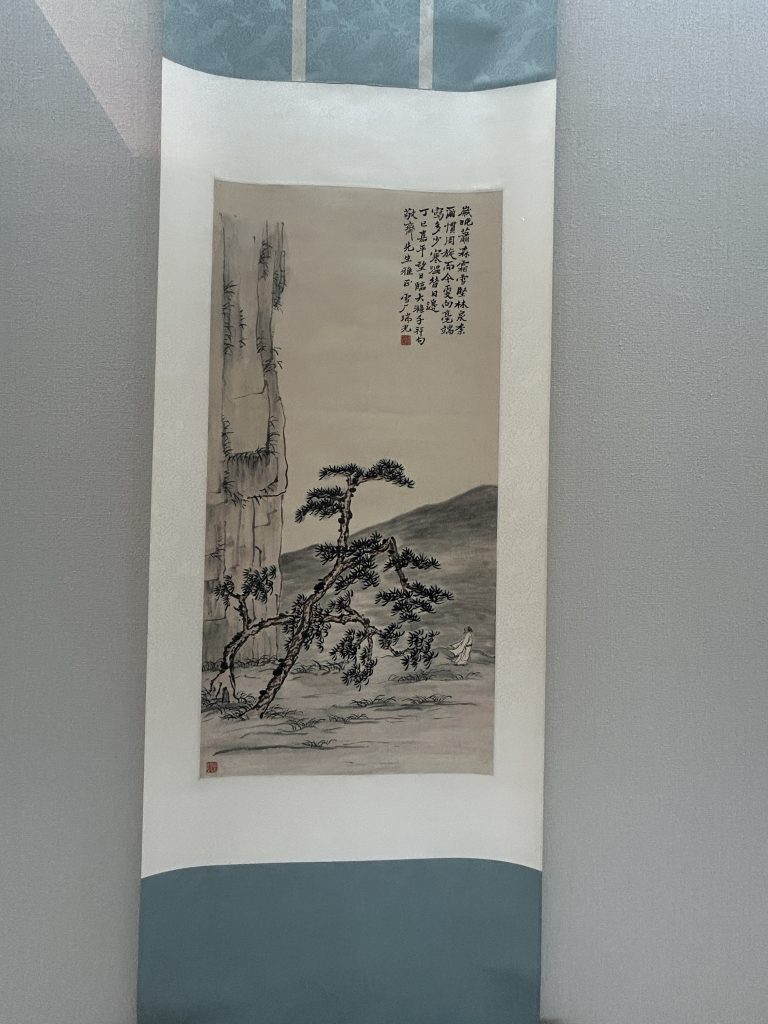

Rui Guang, Yijing Zhi Yang Tu (Republic of China period, China) Collection of Kyoto National Museum

Examples include Zhang Lu’s Wangqi Tu (Ming dynasty, China), Hua Yan’s Qiusheng Fuyi Tu (1755, Qing dynasty), and Rui Guang’s Yijing Zhi Yang Tu (Republican period, China). In Wangqi Tu, a figure gazes into deep mountains and valleys where swirling forms resembling wind or qi can be seen. In Qiusheng Fuyi Tu, a figure inside a residence is depicted alongside trees and leaves outdoors being blown by the wind. The title “Qiusheng Fu” refers to a rhapsody by the Northern Song literatus Ouyang Xiu (1007–1072), who, upon hearing a sound from the southwest one night while reading, asked a servant what it was, only to learn it was the sound of leaves rubbing against each other in the wind. Ouyang Xiu perceived it as the melancholy “sound of autumn,” prompting reflections on impermanence, decline, and aging. In Rui Guang’s Yijing Zhi Yang Tu, inspired by a theatrical work of the same title, one can feel wind blowing from right to left through the swaying pines and the fluttering garments of the literati figure.

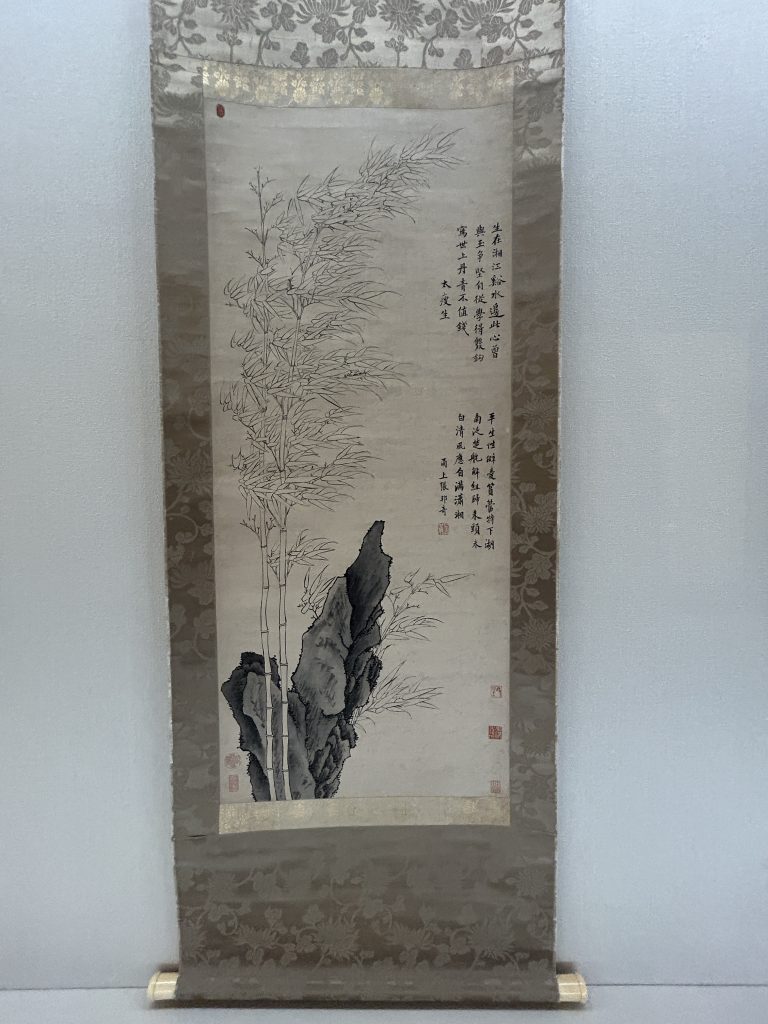

Jin Shi, Shuanggou Zhu Tu (Ming dynasty, China) Collection of Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

The exhibition is organized into two sections: Chapter 1, “Wind Blowing through Landscapes — Weather Expressions in Landscape Painting,” and Chapter 2, “Wind Blowing through Plants — Weather Expressions in Flora Painting.” In Chapter 2, the focus shifts from human figures to plants. Among the highlights is Jin Shi’s Shuanggou Zhu Tu (Ming dynasty, China), depicting bamboo — a plant native to East Asia — bending in the wind. Bamboo was often associated with moral integrity and treated in an anthropomorphic manner. This ties into the literati painting theory of the Northern Song, which held that only persons of character could create truly spirited works. The artist used the “outline method” (gouluo fa) to sharply define contours, leaving the upper part of the bamboo unstained and bent, while solidly anchoring rocks at the bottom to create a dynamic composition with minimal elements, emphasizing contrast and richness.

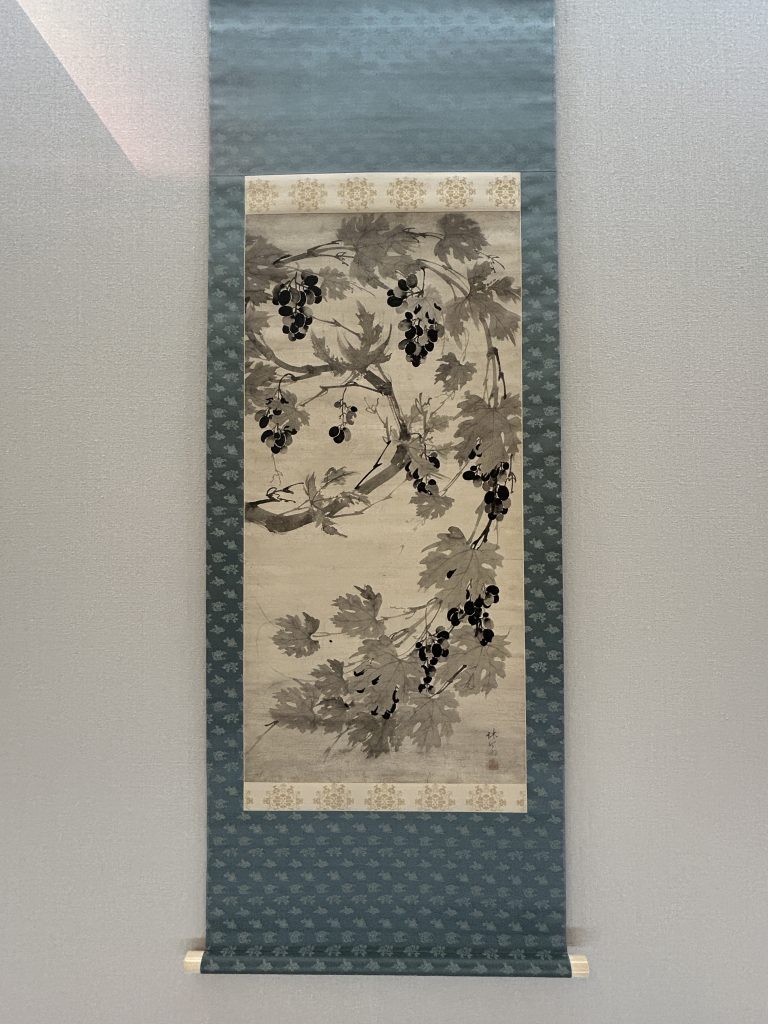

Li Jihu, Putuotu (Joseon dynasty, Korea) Collection of The Museum Yamato Bunkakan

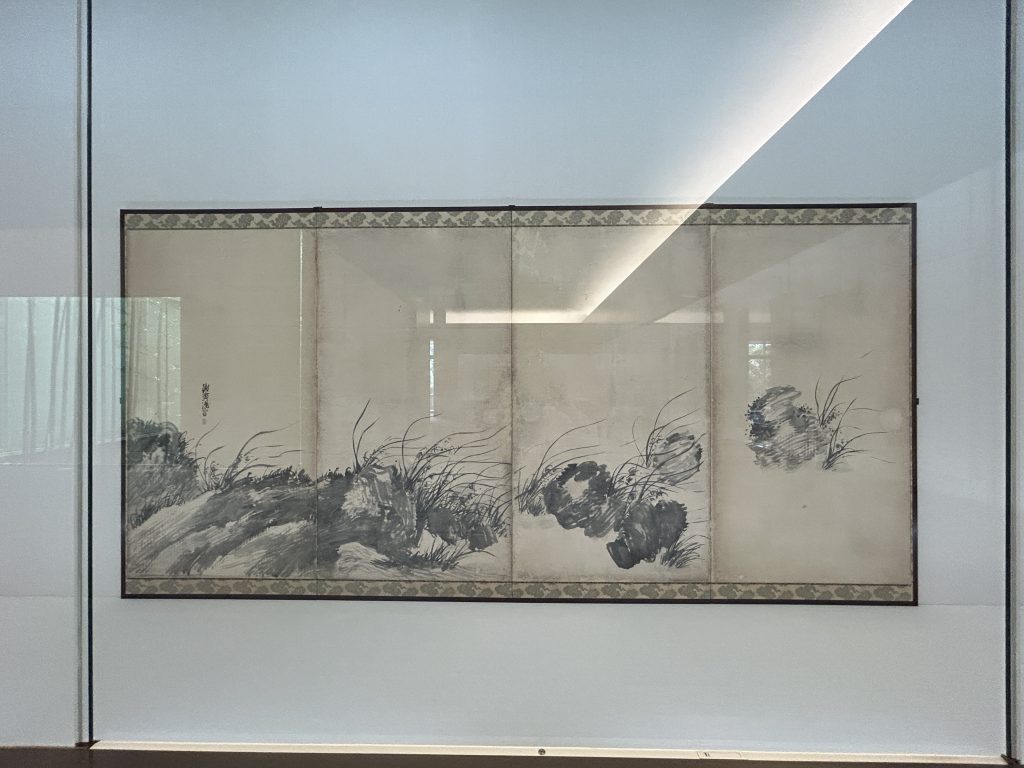

Li Jihu’s Putuotu (Joseon dynasty, Korea), in the Museum Yamato Bunkakan collection, features grapes — a common motif in literati painting — rendered with black for the fruit and varying shades of gray for the leaves, creating a bold, swirling composition across the picture plane. Most striking is Yosa Buson’s Ranshitsu Byobu (Edo period, Japan), which depicts orchids and rocks almost abstractly, as if we can actually feel the wind blowing through them. Even though it is executed solely in ink, it conveys the invisible presence of air.

Yosa Buson, Ranshitsu Byobu (Edo period, Japan) Collection of The Museum Yamato Bunkakan

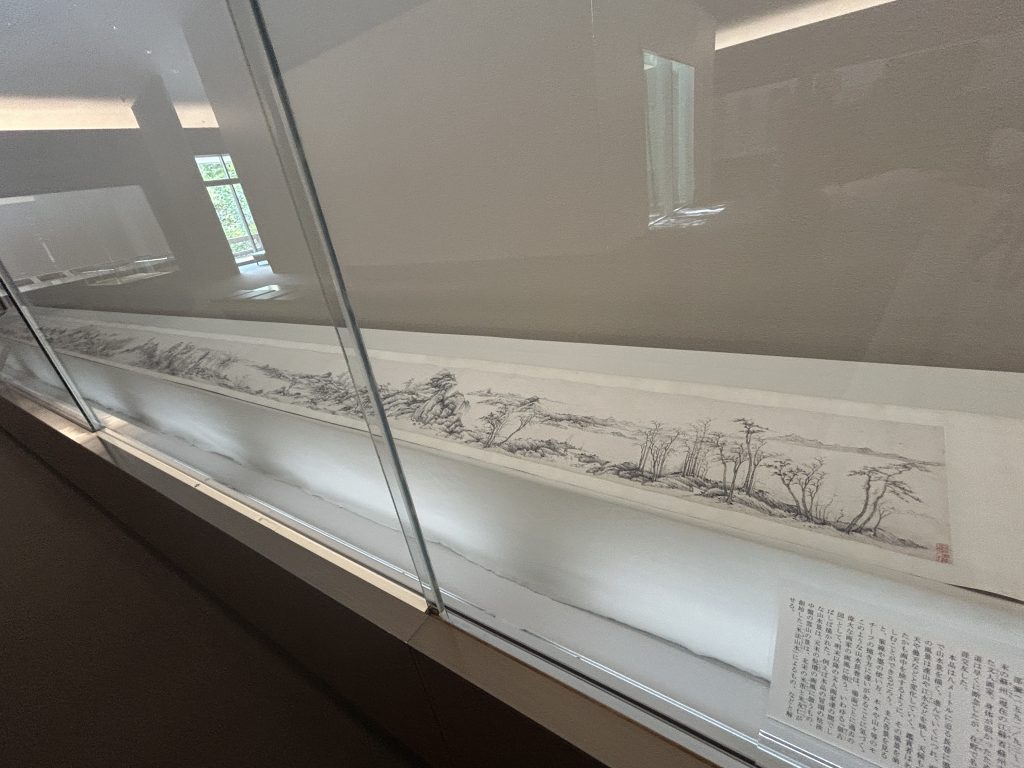

Yet, the characteristic wind of East Asia is a humid wind shaped by the monsoon climate, often transforming into mist or rain. Shao Mi’s Yunshan Pingyuan Tu (Ming dynasty, China) is a long horizontal scroll about eight meters long. Executed in monochrome ink, it portrays ever-changing weather along with mountains and rivers, using different painting approaches in each scene. This “landscape scroll” tradition of emulating past masters’ styles (“Fanggu Tu”) flourished from the late Ming onwards. Particularly notable are the cloud mountain scenes painted using the “Mi dots” technique (Mi dian), originated by the Northern Song literati painters Mi Fu and his son Mi Youren, to depict misty, cloud-shrouded mountains — an expression born from the fusion of climate, weather, and technique.

Shao Mi, Yunshan Pingyuan Tu (Ming dynasty, China) Collection of Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

Shao Mi, Yunshan Pingyuan Tu (detail) (Ming dynasty, China) Collection of Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

Gao Jianfu’s Yanjiang Diezhang Tu (1925), by one of 20th-century China’s leading painters who studied in Tokyo and Kyoto, is painted with layered pale ink reminiscent of the “mōrōtai” (blurred style), capturing rivers and mountains shrouded in mist on a rainy day. In Maruyama Ōkyo’s Shiki Sansui Byobu: Natsu (Late Edo period, Japan), a rainy waterside scene is depicted; thin vertical brush traces suggest a rain-soaked, obscured view.

Gao Jianfu, Yanjiang Diezhang Tu (1925) Collection of Kyoto National Museum

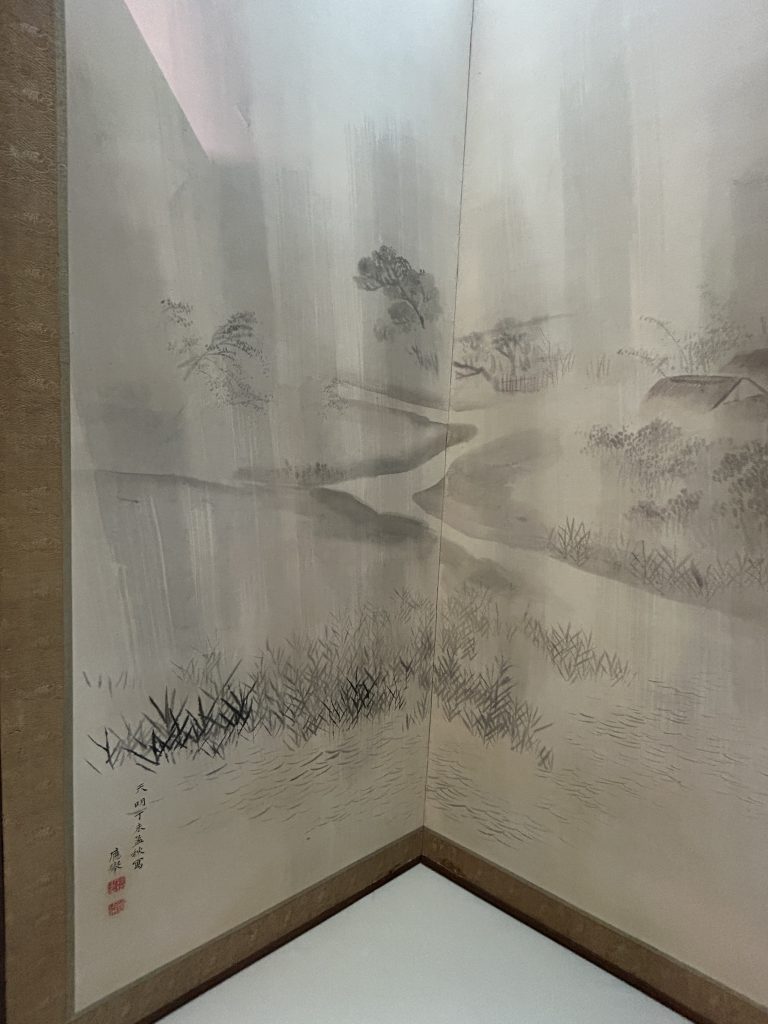

Maruyama Ōkyo, Shiki Sansui Byobu: Natsu (Late Edo period, Japan) Collection of The Museum Yamato Bunkakan

Maruyama Ōkyo, Shiki Sansui Byobu: Natsu (detail) (Late Edo period, Japan) Collection of The Museum Yamato Bunkakan

This exhibition suggests that “weather” as a natural phenomenon — experienced through a shared monsoon climate and common materials like ink, paper, and brushes — is not merely a theme in East Asian art but a profound force that generates the worldview of qi. In harsher, drier climates, nature might appear clearer and more distinct from the human world. But in East Asia, where humid air connects nature and humans and manifests as wind, rain, or mist, it seems only natural to see these as external reflections of the “qi” that resides within us.