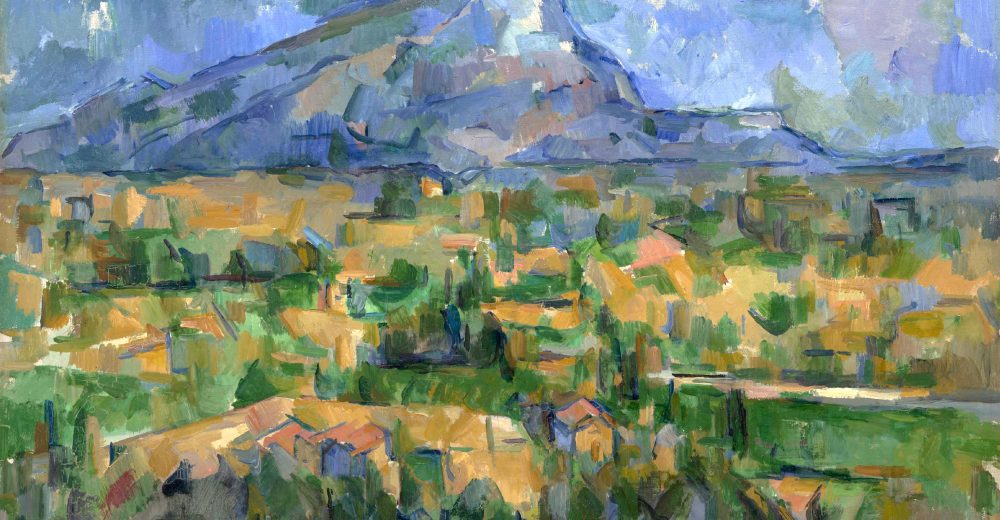

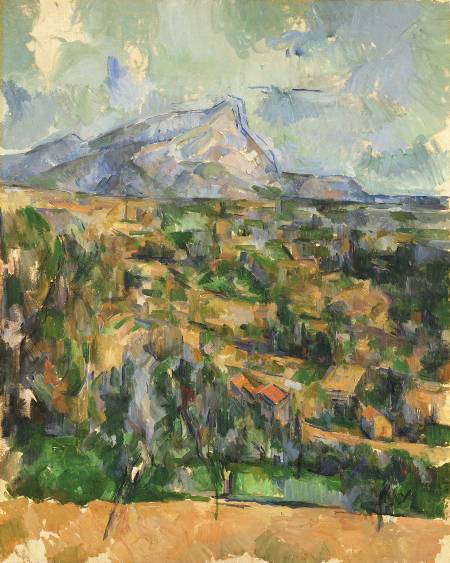

Fig. 1 Paul Cézanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1904-06.

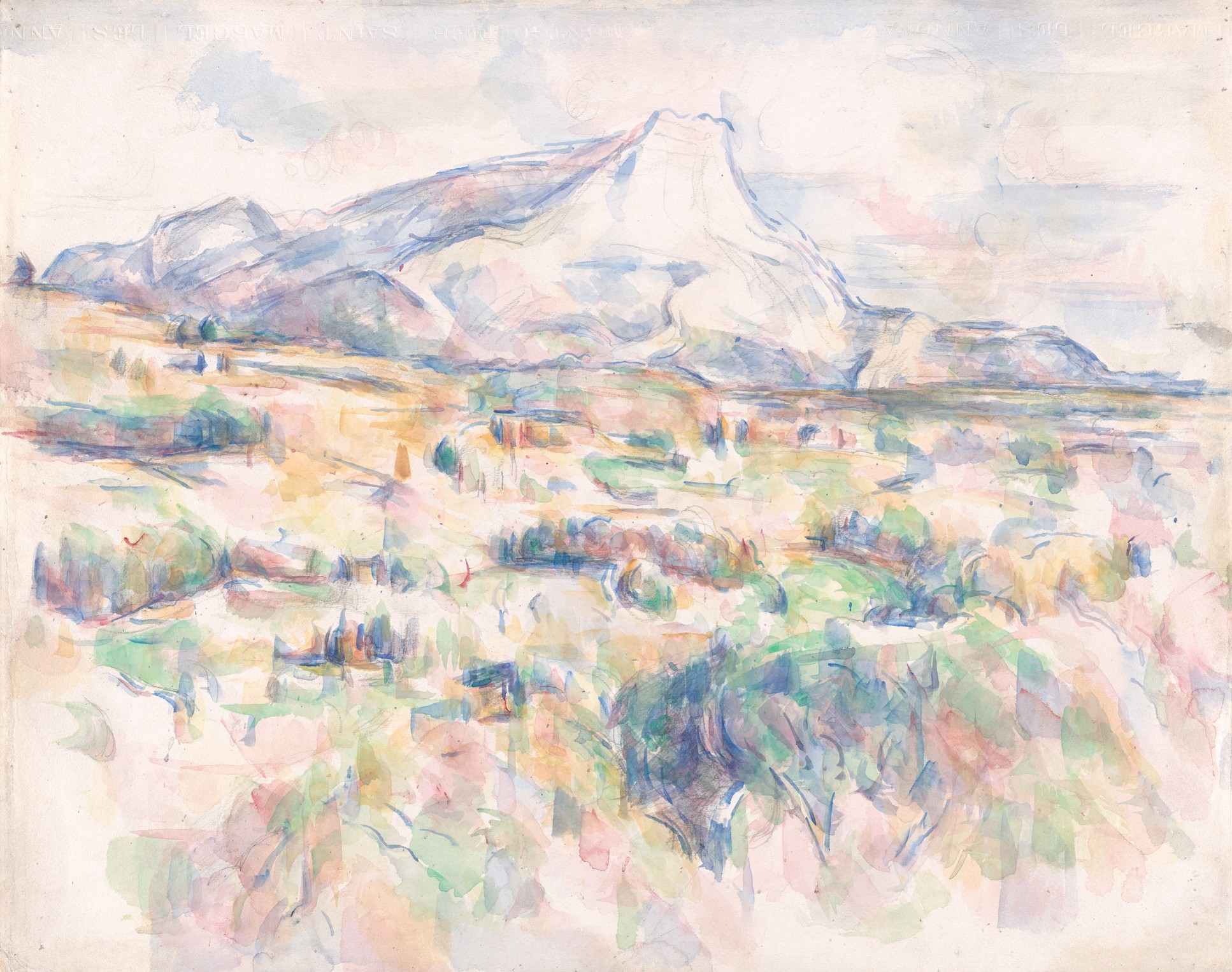

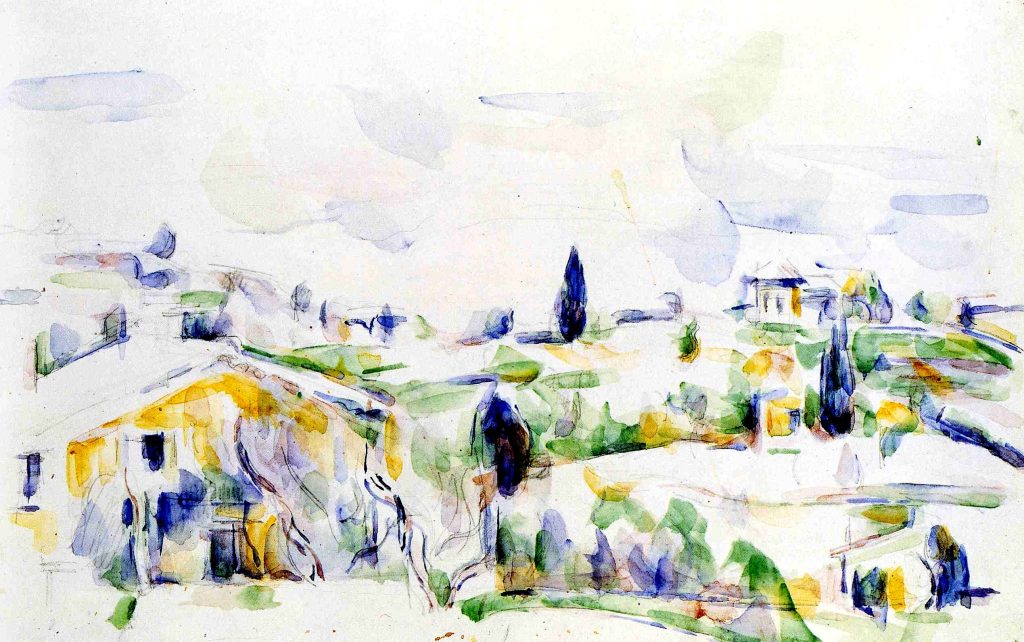

Fig. 2 Paul Cézanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1902-06.

Fig. 3 Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves

(Photographed by the author on August 28, 2006)

In Section 6, we saw that the forms in painting of Paul Cézanne (1839-1906) were influenced by the new visual impressions induced by the railway in the late 19th century.

For example, in Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves (1904-06) (fig. 1) and Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves (1902-06) (fig. 2), from the background toward the foreground, the contours of the objects fluctuate, the brushstrokes become more repeated horizontally, and the lowermost part of the picture is so vague that the viewer seems to be floating in the air. These sensations are very similar to those felt by the scenery seen from the window of a moving train.

Then, how does Cézanne’s famous painting theory, “the realization of sensations,” relate to this transformation of vision brought about by the railway? In this section, we will analyze this issue based on both Cézanne’s works and testimonies.

Firstly, in a letter to his son dated September 8, 1906, shortly before his death, Cézanne wrote about the “realization of sensations” in his paintings as follows:

Finally I must tell you that as a painter I am becoming more clear-sighted before nature, but that with me the realization of my sensations is always painful. I cannot attain the intensity that is unfolded before my senses. I have not the magnificent richness of colouring that animates nature (1).

From this explanation, we can see that Cézanne’s “sensations” are plural, intensely unfolding, and animate nature with magnificent richness of color.

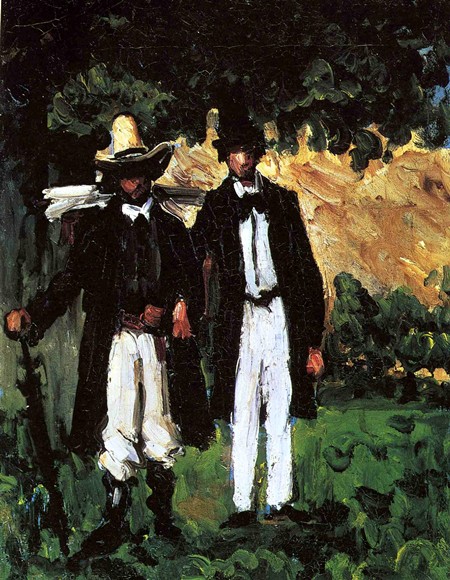

Fig. 4 Paul Cézanne, Marion and Valabrègue Setting Out for Motif, 1866.

In fact, Cézanne had a similar interest from the early stages of his career. In a letter to Émile Zola dated around October 19, 1866, young Cézanne described how outdoor sketching brought a sensation which is unfolded with intensity and animates nature as follows:

But you know all pictures painted inside, in the studio, will never be as good as those done outside. When out-of-door scenes are represented, the contrasts between the figures and the ground is astounding and the landscape is magnificent (2).

From this description, we can see that Cézanne was enthusiastically engaged in outdoor sketching using tubed oil paints, which had recently become practical thanks to advances in science and technology. We can also see that in such painting, the “contrasts between the figures and the ground” is strikingly intense, and nature is lively. This can be said to be the “transformation of vision caused by natural light” in outdoor sketching. A notable example of this is the work created during this period, Marion and Valabrègue Setting Out for Motif (1866) (Fig. 4).

At that time, outdoor sketching in natural light was an avant-garde experimentation in the art world. When Cézanne firstly moved to Paris in 1861, he learned this method from future Impressionist painters such as Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro. Even after returning to his hometown of Aix, Cézanne continued to share his interest and practice of outdoor sketching with them.

Fig. 5 The Pool of Jas de Bouffan

(Photographed by the author on August 23, 2006)

Fig. 6 Paul Cézanne, The Pool of Jas de Bouffan, c. 1878.

What should be noted here is that in outdoor sketching, the depiction of the object becomes more primary-colored and pointillistic in order to respond to the intense and changeable outdoor light. Along this line, Cézanne more learned what is known as “divided brushstrokes” from Pissarro in Pontoise around 1871. Furthermore, a letter to Pissarro dated July 2, 1876 shows that Cézanne continued his own research even after he left Pissarro.

The sun here is so tremendous that it seems to me as if the objects were silhouetted not only in black and white, but in blue, red, brown, and violet. I may be mistaken, but this seems to me to be the opposite of modelling (3).

From this comment, we can see that Cézanne felt an object directly irradiated by sunlight being appeared to float as a plan, as a flat surface like silhouette, due to the intensity of the reflected light. Furthermore, we can also understand that he perceived these plans not only as white or black, but also as various colors, such as blue, red, brown, and purple.

In other words, the sensation that Cézanne first pursued as a painter can be interpreted as the primary-colored flattening of visual object in outdoor. An example of this transformed vision caused by the sunlight can be seen in The Pool of Jas de Bouffan (c. 1878) (Fig. 6), which was created during this period (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7 Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves

(Photographed by the author on August 28, 2006)

Fig. 8 Paul Cézanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1902-06.

Fig. 9 Paul Cézanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves, 1904-06.

In fact, if we compare his similar works in watercolor and oil painting, we can see that Cézanne first perceived his objects as primary-colored plans (Fig. 7-9). Especially in his later years, these primary colors were refined into the three primary colors of red, blue, and yellow, and green, which is the complementary color of red.

What is noteworthy here is that his paintings, composed of the primary-colored plans of the objects, resemble the view from the window of a moving train, where objects appear as spots due to the high speed. In other words, it is highly likely that Cézanne, in his pursuit of the sensation of the transformation of vision caused by the sunlight in outdoor sketching, associated the painted scene with a different sensation of the transformation of vision bring about the railway, which he experienced in daily life.

Fig. 10 A Train Window Scenery on the Aix-Marseille line

(filmed by the author on August 26, 2006)

Fig. 11 Paul Cézanne, Landscape in Provence, 1895-1900.

Fig. 12 Paul Cézanne, Turning Road, c. 1904.

In real, looking out the window of a speeding train, horizontal ridgelines stand out, and from far to near, the objects become more horizontally distorted, speckled, and fly away. Furthermore, the foreground is lost due to the high-speed motion, and passengers feel gliding through the scenery (Fig. 10).

Correspondingly, in Cézanne’s Landscape in Provence (1895-1900) (Fig. 11) and Turning Road (c. 1905) (Fig. 12), the ridgelines are prominent across the entire screen, and from the background toward the foreground, the contours of objects become more blurred, and the horizontal repetition of brushstrokes is more emphasized. Moreover, the lowermost part of the picture is unclear, causing the foreground to disappear, giving the viewer the impression of floating through the landscape.

In summary, the sensation that Cézanne was trying to express as a painter was, first and foremost, the transformation of vision induced by the sunlight. We can assume that in the process of pursuing this, Cézanne also incorporated another sensation, namely the transformation of vision induced by the railway.

In this context, it is conceivable that Cézanne’s difficulty with precise drawing also helped him to recall the multiple perspectives and distortions of objects seen while riding a train. This is why we can understand that the “sensations” that Cézanne was trying to realize were plural.

When Cézanne confesses that it is difficult to realize his sensations, the reason must have been not only the dazzling brightness of objects in the transformed vision caused by the outdoor light, but also the rapid movement of objects in the transformed vision brought about the railway. In any way, it can be insisted that Cézanne was trying to paint the various new visual realities produced by the development of modern technology in the late 19th century as various sensations.

In conclusion, I would argue that the reason Cézanne came to be called the “father of modern painting” was not only because of his exceptional artistic sensibility, but also because he was deeply rooted in such historical and social realities.

Notes

(1) Paul Cézanne, Correspondance, recueillie, annotée et préfacée par John Rewald, Paris: Bernard Grasset, 1937; nouvelle édition révisée et augmentée, Paris: Bernard Grasset, 1978, p. 324. (Paul Cezanne, Letters, edited by John Rewald, translated from the French by Marguerite Kay, New York: Da Capo Press, 1995, p. 327.)

(2) Ibid., pp. 122-123. (Ibid., pp. 112-113.)

(3) Ibid., p. 152. (Ibid., p. 146.)

【Related Posts】

■ Tomoki Akimaru, Cézanne and the Railway (1) – (7): A Transformation of Vision in the 19th Century.

Cézanne and the Railway (1): A Hidden Origin of Modern Vision

Cézanne and the Railway (2): The Earliest Railway Painting Among French Impressionists

Cézanne and the Railway (3): His Railway Subject in Aix-en-Provence

Cézanne and the Railway (4): His Railway Subject in Médan, Pontoise, Gardanne, and L’Estaque

Cézanne and the Railway (5): A Stylistic Analysis of His Pictorial Form

Cézanne and the Railway (6): The Influence of the Machine on the Shift from Subject to Form

Cézanne and the Railway (7): What is the Realization of Sensations?

■ Tomoki Akimaru, Fauvism and the Automobile: A Transformation of Vision in the 20th Century.

● Marie Rauzy — A contemporary French painter descended from Paul Cézanne