Hello! 你好! 안녕하세요! こんにちは!

I am Tomoki Akimaru, an art critic and curator from Japan.

I listened to your lectures with great interest today. Basically, I agree with every point you make. I think this is because, although we come from different countries and have different positions, compared with the West, as East Asian countries, we are a community with a shared future. The most important thing is that art is universal to all humankind. First, I want to say that I am interested in cultural diversity and commonality.

I’m from Japan. Japan is known as the “Far East”. Geographically speaking, “Far East” refers to the easternmost country in the world. In cultural history, Japan was the easternmost terminus of the Silk Road connecting the East and the West. Now, I happen to be sitting in your easternmost seat, in other words, in the rightmost seat. So, I want to talk about cultural exchange through art. In particular, I want to talk about issues regarding tradition in contemporary East Asian avant-garde art.

Basically, any country’s culture has two directions. One direction is based on one’s traditional culture, and the other is influenced by foreign culture. I think we need both. Because if we want to live a better life, it’s essential to give full play to our good points and incorporate the good points of others. I believe that is the same for art, a branch of culture.

Japan has always incorporated foreign cultures into its own traditional culture since ancient times. Until the mid-19th century, Japan basically studied Chinese and Korean culture. Since the mid-19th century, Japan has mainly studied Western culture. The interesting thing here is that even if foreign cultures influenced the traditional clture, its traditional characteristics still emerge. And I also believe that is the same for art, a branch of culture.

Gutai Art Association and Mono-ha, two of the most representative art movements in contemporary Japan, have both Western and traditional tendencies.

Fig.1 Kazuo Shiraga, Tenfusei Hakutencho, 1963

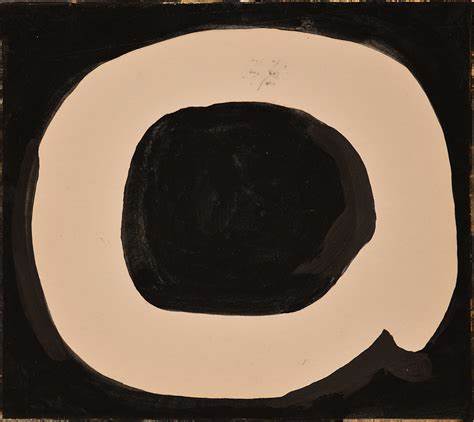

Fig.2 Jirō Yoshihara, No.T0281, 1965-1970

First, the Gutai Art Association, active from the 1950s to the 1970s, was influenced by contemporary Western Abstract Expressionism and Informalism. Works by Jackson Pollock and the Gutai artist Kazuo Shiraga, who used their bodies to apply paint to canvas roughly, are very similar (Fig. 1). At the same time, Shiraga also said that his works were influenced by the “bloody ceiling” in Buddhist temples. “Bloody Ceiling” is the Japanese custom of using blood-stained wooden boards on the ceilings of Buddhist temples to commemorate fallen soldiers. In addition, the paintings of Jiro Yoshihara, president of the Gutai Art Association, also reflect the “Circle painted with a single stroke” of Zen, one of the Buddhist sects (Fig. 2). “Circle painted with a single stroke” is a pictorial representation of the ideal psychological state of human beings in Zen Buddhism. In other words, the Gutai Art Association reflected contemporary Western influences and a traditional Japanese mentality fostered through Buddhism. Starting in 538, Japan formally learned Buddhism, which originated in India through China and Korea.

Fig.3 Nobuo Sekine, Phase-Earth, 1968

Photo: ©Osamu Murai

Fig.4 Susumu Koshimizu, Snow Departs from Snow, 2010

(Exhibition view of ‘Grief and Anima II’ at Ryosoku-in Temple in 2021)

In addition, Mono-ha, active around 1970, was influenced by Western minimalist art and land art simultaneously. We can easily find similarities between Donald Judd and Richard Long (who used as simple materials as possible to create abstract installations) and the Mono-ha representative artists Nobuo Sekine and Susumu Koshimizu (Fig. 3). At the same time, Sekine and Koshimizu also created works inspired by the gardens of Buddhist temples and shrines. In other words, Mono-ha is not only influenced by contemporary Western influences, but also encompasses traditional Japanese beliefs which perceive the sacredness in nature. To confirm this, I organized an exhibition of Mono-ha at a large historical Buddhist temple in Japan (Fig. 4). Isn’t this belief in nature a traditional mentality prevalent not only in Japan but throughout East Asia, including China and Korea? I believe that now is the time to focus on these commonalities through art as we face a crisis in our natural environment.

Fig.5 Yusen Fujii, Lotus, 2007

Let me give you another example. An artist currently active in Japan is named Yusen Fujii. His Chinese name is Huang Zhi. He was born in Jiangsu Province, People’s Republic of China in 1964. He graduated from the Art Institute of Suzhou University and was a lecturer at Beijing Institute of Fashion Technology. After coming to Japan in 1992 and marrying a Japanese woman, he was active in Kyoto for about 30 years. Yusen has painted many ink paintings at Japan’s famous Zen temples, such as Kinkaku-ji Temple. Yusen’s painting method when he just came from China to Japan was to fill the entire painting with patterns. It can be said to be a Chinese additive aesthetic. In this regard, after Yusen gradually learned about traditional Japanese painting, half of his paintings were intensively painted as before, and the other half boldly began to leave blank spaces (Fig. 5). This is considered Japan’s subtraction aesthetic. Although Yusen is Chinese, he can also understand Japan’s traditional aesthetics. This is because the Chinese and Japanese are the same human beings. Although the development directions of aesthetic consciousness in China and Japan are different, human beings are born with these two aesthetic consciousnesses, so if we show each other, we can understand each other. Therefore, as a painter, Yusen said he wants to create new beauty in the world while trying to convey Chinese aesthetic consciousness to Japan and Japanese aesthetic consciousness to China. I think Yusen’s thoughts and works will significantly help in thinking about international cultural exchanges and artistic activities.

I believe that by respecting each other’s culture through art, we can respect each other as human beings. At the same time, we can explore our tradition in avant-garde art and find our differences and commonalities. The world is currently facing various threats and problems, and I propose that in order to achieve collaboration and overcome them, we should pay attention to our commonalities through art.

Finally, I summarize the concepts related to art. In ancient Greece, “techne” referred to any skill used to achieve a specific purpose. When it was translated into Latin and introduced to Europe, it became “ars”. In the West, when the scientific revolution occurred in the 17th century and mathematically precise “Science” was established, only those things united to science were extracted from “techne/ars” and became “technique”. In addition, science and technique combined in this way are called “technology”. On the other hand, the remaining part of “techne/ars” is thus called “art”. Therefore, “art” is a complementary concept to “technology”. Simply put, the definition of art is “skill that cannot be repeated rationally.” Ultimately it’s any idea based on personality. We call it “creativity”. In this regard, although “art” is a concept originating from the West, it can be said to be universal to all humankind. And I would like to point out that among these arts, the more tactile ones are called “craft” or “practical art”, and the more visual ones are called “fine art” or “pure appreciation art”.

(English translated by Yun CHEN)