SOICHI YAMAGUCHI×SAKI MATSUMURA “MATERIALS” MU GALLERY Exhibition view Photographed by Ken Kato

One of my interests, apart from art criticism, is research into color. We can learn an awful lot by looking at the history of painting from the point of view of color. To take a somewhat famous example, the Impressionists are known to have used paint tubes in order to create their pictures quickly while outdoors. The 19th century saw great strides forward in the field of chemistry, and this led to the discovery of a great many new pigments and dyes. The development of a means to artificially produce rare pigments like ultramarine was one particularly lucrative example.

In fact, these developments in chemistry are related to the area of photography, which allowed light to be recorded onto photographic paper. Johannes Vermeer was one painter who saw the potential of optical instruments for painting, but he was far from the only one. Optical instruments, incorporating components such as lenses and mirrors, have long been in use by artists as an aid in the production of preliminary sketches. According to David Hockney, this history can be traced back to around 1430.[1] It was with the chemical revolution of the 19th century, though, that it became possible to record light images on media such as light metal plates and photographic paper. The birth of photography led to the demise of realistic painting, but it also led to the creation of a new kind of painting that favored the portrayal of transitions of light and impression: this was the advent of modern art. Put another way, photography and modern art can be considered as two sides of the same coin, both having come about as a result of the same scientific advancements.

On top of this, the development of new means of transport, such as the locomotive engine and the steamship, also contributed to a change in artists’ perception. With the increased ease of movement to distant locales, another important development was the rapid increase in the number of outdoor subjects. For the Impressionists, that meant the region of Normandy, while the Neo-Impressionists, Post-Impressionists, and Fauvists favored the south of France. With this geographical shift came a changeover to a Mediterranean climate, and the color used in these paintings rapidly became much more vivid. Color analysis reveals that, while the Impressionists used intermediate levels of saturation and brightness, artists like Vincent Van Gogh, Paul Signac, and Henri Matisse made much greater use of high-saturation colors. It is a certainty that climate and light have an effect on painting, and the step-by-step process from Impressionism to Fauvism can be seen as a perfect example of this phenomenon.

After World War II, the center of the art world shifted across the Atlantic to New York, and there was an increase in demand for purity of painting. Ultimately, this led to the creation of paintings such as color field paintings, which consist of nothing but color covering the screen, in the style of color field painting. While this might lead one to believe that the connection between climate and painting had been severed, that very abstraction can be said to resemble the fully-planned artificial cityscape of New York. Some painters, such as Hockney, moved to the West Coast of the United States and adopted flatter and more vividly colorful styles.

Meanwhile, in Japan, the methods of the Impressionists were imported in a modified form by artists such as Seiki Kuroda. The paintings that resulted did indeed have more vivid colors than those of earlier generations. But Japan is completely surrounded by the sea and has an atmosphere that contains a great amount of water vapor, and as a result, even employing the techniques of the Impressionists, Japanese art rather could be thought of as having become “fainter” and “hazier”. The same can be said of the mōrōtai (indistinct or vague) painting of the Nihonga painters who adopted the methods of the Impressionists, such as Yokoyama Taikan and Hishida Shunsō. Amidst the climate and environment of Japan, color became less and less vivid, and more hazy and vague. Up until the 20th century, and perhaps beyond, even with improvements in art materials, the climate itself did not change so rapidly. Whether for this reason or some other, it can definitely be said that many Japanese painters and designers don’t have a good handle on color. They tend to rely more on their eye for materials and textures. In a climate with a large amount of atmospheric water vapor, where sunlight is dispersed, it is easy to arrive at a style that is, overall, flat and texture-oriented. This can be said of the monochrome landscapes of traditional Japanese art. The reason for this is not simply that this style is a reflection of the characteristics of the outside world. Surely another factor at play is that, without much shading, it was difficult for Japanese artists to get a grasp on texture, and so it was necessary for them to develop a sense for it.

Today, technology and movement are interacting with, and causing changes to, perception and painting in a more complex way. With the growth of the Internet and social media, we now see images from distant places on a daily basis. Whether we are traveling or permanently relocating to somewhere else, or just staying put, we tend in any case to spend most of our time glued to PC or smartphone screens. Even without moving, it is possible to view the sights of other places, and we can see distant places even while moving. Nevertheless, the climate—the environment—in which an artist grew up undoubtedly forms the basis of her feeling for texture to a greater or lesser degree.

Against this backdrop, there is one place that has nothing to do with climate: outer space. In space, there is nowhere that is blocked from light by the atmosphere. Light out there is even stronger than the Mediterranean or the American West Coast, and shading is stark and clear. Indeed, the reason that Galileo was able to draw the surface of the moon in such detail is the lack of an atmosphere.[2]

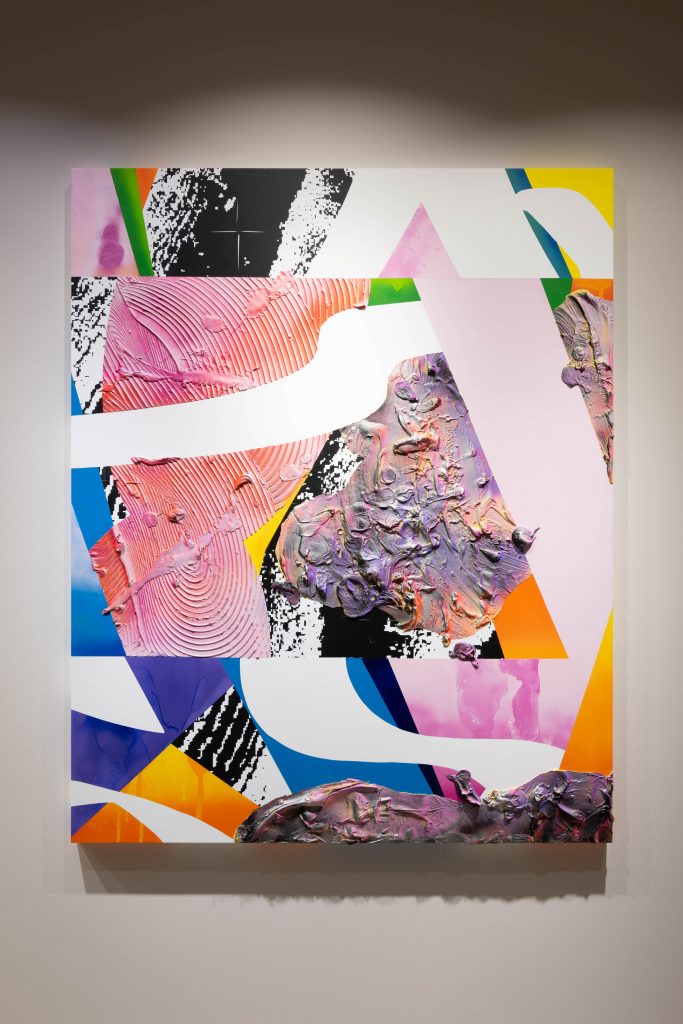

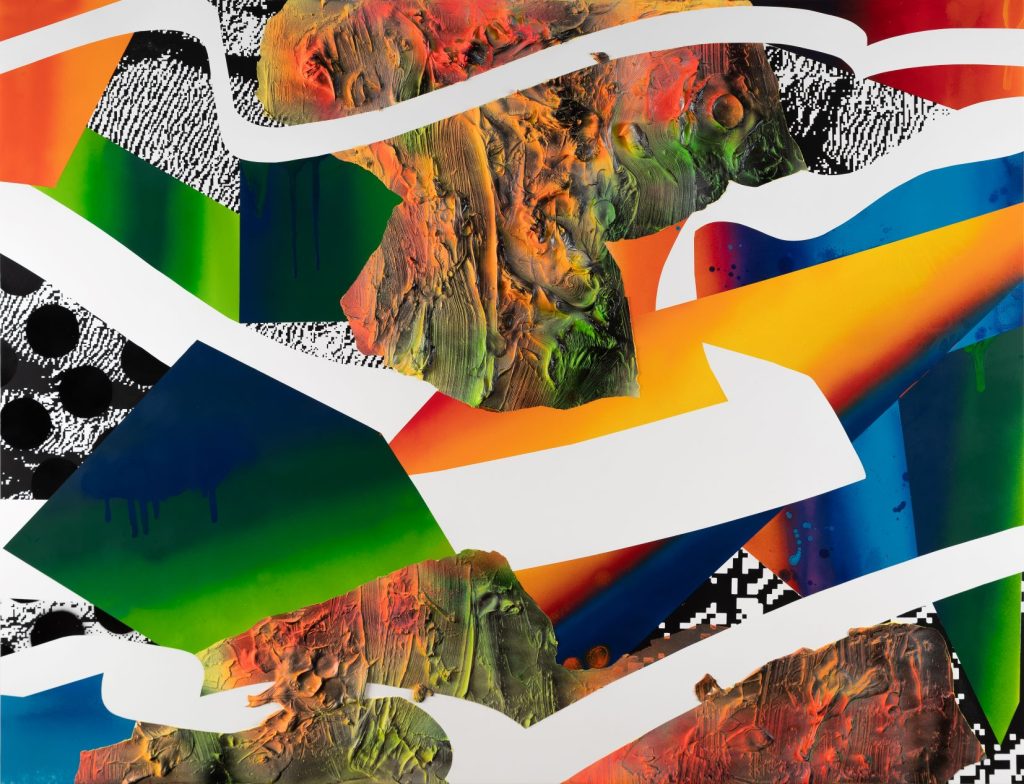

Saki Matsumura takes as her motifs those subjects that can be said to be universal to all humans, namely satellite images of celestial bodies such as Mars and—like Galileo before her—the moon. She does not, however, merely paint them as is. Rather, she breaks them down into a variety of different elements, portraying each in a different color or layer of material. Her screens are made up of multiple layers, with fault lines that switch, run through, and interrupt the upper and lower layers. The parts of the image that are concealed by these fault lines are left up to the viewers to complete in their imaginations. This is the sensory phenomenon known as “amodal completion”, whereby the viewer completes the missing portion in his or her imagination, and it can definitely be said that there are few more complex examples than this.[3] The completion is made all the more difficult by the fact that there are places where the divided layers are not connected. This is also similar to how our memories are broken up day after day by smartphones.

Moreover, while the material is piled up through the use of modeling paste, shading is added by using fluorescent spray, creating a diorama of the surface of Mars or the moon. This is reminiscent of Red Relief Image Mapping, which represents slopes with red saturation and ridge valleys with brightness.[4] Painting, with the purification of Modernism, has dispelled illusions and been flattened out, which in turn has resulted in a trend toward specialization of materials, but Matsumura adds shading to her materials, giving birth to ever more complex tactile illusions. On the other hand, because the satellite images are not used as is but rather coarsely printed by silkscreen to the point that their original appearances cannot be discerned, it is very difficult to go from there to picturing the original image.

Just as with the divided brushstrokes of the Impressionists and the stippling and analytical cubism of the Neo-Impressionists, Matsumura’s works take the multitude of colors, materials, and patterns that emerged from a single image, break them down, and then unify them on the canvas. This is then distinctly connected, inside the brains of the viewers, with images that evoke the surfaces of Mars or the moon. But how is it that we are able to overcome the intricate web of overlapping information in these multiple layers, materials, and illusions, and come back to the original image that Matsumura saw? The answer is, without doubt, to be found in the bridge created by Matsumura’s ingenious artistry.

The geographical sense that can be observed therein can surely be traced to the artist’s background, having been born and raised in Nozawaonsen Village in Shimotakai, Nagano. In the winter, this area experiences many days of heavy snowfall, on which you can’t see even a few feet ahead, but on sunny days one can see mountains far off in the distance. Skis are an everyday tool in that region and would, by sliding over the snowy ground, have allowed the young Matsumura to feel the shape of the land directly. This sensation is a modern development, since skis as a transportation device did not become commonplace until relatively recently. Before that, there was no sensation of maintaining one’s equilibrium while moving at a high speed across sloping land.

The sense of “vertigo” that one feels when looking at Matsumura’s paintings is not merely an illusion. Rather, it can be said to be a true recreation of the physical sensation one experiences when moving rapidly up and down, left and right, on a roller coaster or when skiing. The conversion of visual information such as satellite photos and relief maps into substantial and tactile three-dimensional information may also be something that simply comes naturally to Matsumura.

The images Matsumura paints are at once a reflection of the sensations that we experience in an era of digital networks and something based on a textural perception born out of Japan’s natural climate, a physical sensation cultivated from a young age, and a sensitivity to seek out new horizons and to boldly engage with new fields. No doubt the ongoing climate change and space exploration of the 21st century will prompt further changes in Matsumura’s senses, to be reflected in future works. Through Matsumura’s experimentation, it becomes possible for us as viewers to connect in our minds the scattered layers; from her materials and illusions, for us to pull distant planets into realms of space and our physical bodies. That is a phenomenon of sliding over the surface of planets, a voyage of imagination and creativity, totally new to the 21st century.

[1] Hockney, D., 2010: 183. Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the lost techniques of the Old Masters (Expanded Edition). Translated by T. Kinoshita. Tokyo: Seigensha.

[2] Galilei, G., 2017: 22–43. Sidereus Nuncius. Translated by K. Itō. Tokyo: Kodansha.

[3] Miura, K., 2007: 97. Chikaku to Kansei no Shinrigaku (Shinrigaku Nyūmon Kōsu 1). Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

[4] Red Relief Image Mapping (RRIM, Sekishoku Rittai Chizu in Japanese) is a method of representing relief maps developed by Asia Air Survey, Co., Ltd. It uses digital elevation model (DEM) data to represent elevation by showing slopes in red saturation and ridge valleys in brightness. Because this method allows a direct sensory depiction of the shape of the land, a Red Relief Image Map of the moon has also been created. https://www.rrim.jp/ (Accessed November 4, 2022.)

Translated by Ian Suttle

From “Saki Matsumura: A Collection of Works” (Sun M Color, 2023)