“Japaner im Revier” is a project that Naho Kawabe, an artist who uses coal as material for her work, started in 2021; I joined the project as a research partner. In 2022, we investigated relevant written sources and carried out fieldwork in the Ruhr region. At the same time, we followed the traces of Japanese coal miners who lived in Germany and conducted various interviews. In April 2023, we published a report of our findings under the title Japaner im Revier.

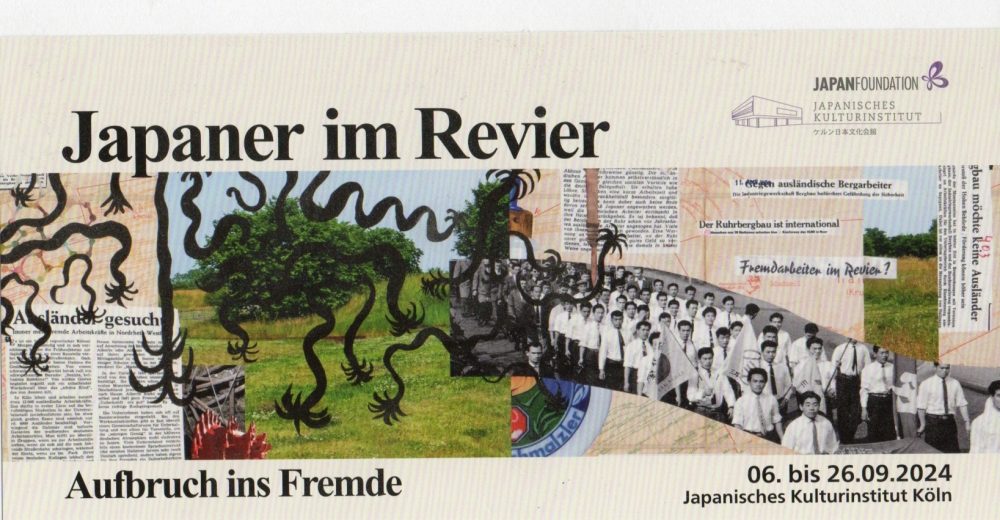

Under the title “Japaner im Revier: Aufbruch ins Fremde (Japanese People in the Ruhrgebiet: Border Crossers),” an exhibition of Naho Kawabe’s work and related historical materials will be held at the Japan Cultural Institute (the Japan Foundation) in Cologne. The exhibition runs from September 6 until September 26, 2024, and a symposium will be held during this time.

Naho Kawabe, Japaner im Revier, Teil A/ Teil B Hamburg 2023

Work as a Personal Asset, and the Search for Heavy Tools

Work is […] a personal, steadfast, nontransferable quality, fit to be moved beyond borders and properties.— Julia Kristeva, 1988 [ 1 ]

During the 1950s and 1960s, many Japanese coal laborers worked in groups in Germany’s Ruhr region, on the outskirts of Düsseldorf in the Western part of the country. The inspiration for the present project is Naho Kawabe’s idea that these people—who came to Germany at a time when international travel was not easy, and who carried out extremely physical labor—might in fact have embodied Julia Kristeva’s idea that work is “the only property that can be exported duty free.” [ 2 ] The notion of carrying out physical labor in a foreign land where one does not understand the language, and that this physical labor itself is the only personal asset one can rely on, overlaps with Kawabe’s way of life as an artist who creates something from nothing. As Kawabe began her research, she found the following phrase among the documents related to Japanese coal miners: “At that time, the tools used in the coal mines differed between Germany and Japan, and the tools made to fit the physique of the Germans were heavy and difficult to use.” This connects to Kawabe’s own experience in Germany, casually picking up tools at a hardware store and being astonished by their weight. Kawabe empathized with these workers given their smaller physique compared to Westerners, together with the pride that is associated with the difficult to imagine harshness of their underground labor. She wanted to hear stories from people who actually worked in the mines, and if that wasn’t possible, to at least speak with their families. In this way, Kawabe’s enthusiasm has been the driving force behind this project.

As a researcher tasked with investigating conditions from about 60 years ago, I thought it would make sense to look into a wide range of published materials (books, newspapers, magazines), organize that information, and then carry out interviews on that basis. Usually, research involves surveying the field of existing research, and then finding one’s own individual perspective within it. Thorough preliminary research was required here, because simply asking questions to people out of plain curiosity might lead to answers that do no more than repeat the findings of existing research, to say nothing of the ethical considerations that come into play when conducting in-person interviews.

Two books on Japanese coal miners in Germany were published in the 2000s, and it was also possible to find various essays and newspaper reports. [ 3 ] Even so, Kawabe was intent on hearing testimonies in the flesh, because her interest exceeds recorded historical fact; she is also keenly interested in sensation. On this point, Kawabe has said: “I wanted to hear about the personal experience of being inside a mine, with all five senses. Only someone whose body has felt this can speak of it.” [ 4 ] In other words, she wanted to know a sensory and relational experience that cannot be reduced to something objective. Perhaps this direct approach is more effective than the more strictly historical method from which it departs.

Lampe (Initiativkreis Bergwerg Consolitation) and Naho Kawabe, Halter, 2024 ©︎studio pramudiya / npi

Diachronic and Synchronic Perspectives

All told, then, there was a gap between Kawabe’s method and my own inclination for research that would fit standard protocols. On this point, the graphic designer Shunsuke Onaka raised the notion of “diachronic” and “synchronic” perspectives. [ 5 ] A diachronic perspective is one that arranges and presents various facts in chronological order. By contrast, the synchronic perspective involves taking a snapshot-like view of language at a specific moment in time, without considering chronology. In the field of linguistics, this synchronic perspective refers to examining the structure and various uses of language that are specific to a particular time period. Meanwhile, the diachronic perspective involves comparing language from one era with the same language in another era to explore how it developed. To sum things up somewhat drastically, we might say that the synchronic perspective deals with linguistic variations at a point in time, while the diachronic perspective deals with linguistic changes across history.

My own attitude towards history is diachronic, which is why I felt it was important to look back across the printed record, and all manner of written descriptions, before starting to conduct interviews. Or perhaps I could say that I was looking for a perspective that might emerge from these historical documents. By doing so, I thought that the overall direction of the research would be clarified, and that the accuracy of the narration would be enhanced. On the other hand, Kawabe was after something like variation: to dive into the past, and to try to find experiences, memories and sensations that were highly specific to the lives of certain people, without regard for how to organize them from the present moment. Clearly, such things do not fit into a mode of historical narration that has a single orientation or goal.

Naho Kawabe, 4 1/2, 2024 (detailed view) ©︎studio pramudiya / npi

To Synchronize with the Past

Today, it is very common for contemporary artists to produce their work through research methods that address social concerns, or the historical background of specific regions. [ 6 ] While some of this work elevates information and invites the audience to a different level of experience, other artists present their research materials as infographics, creating works that serve as enlightening statements.

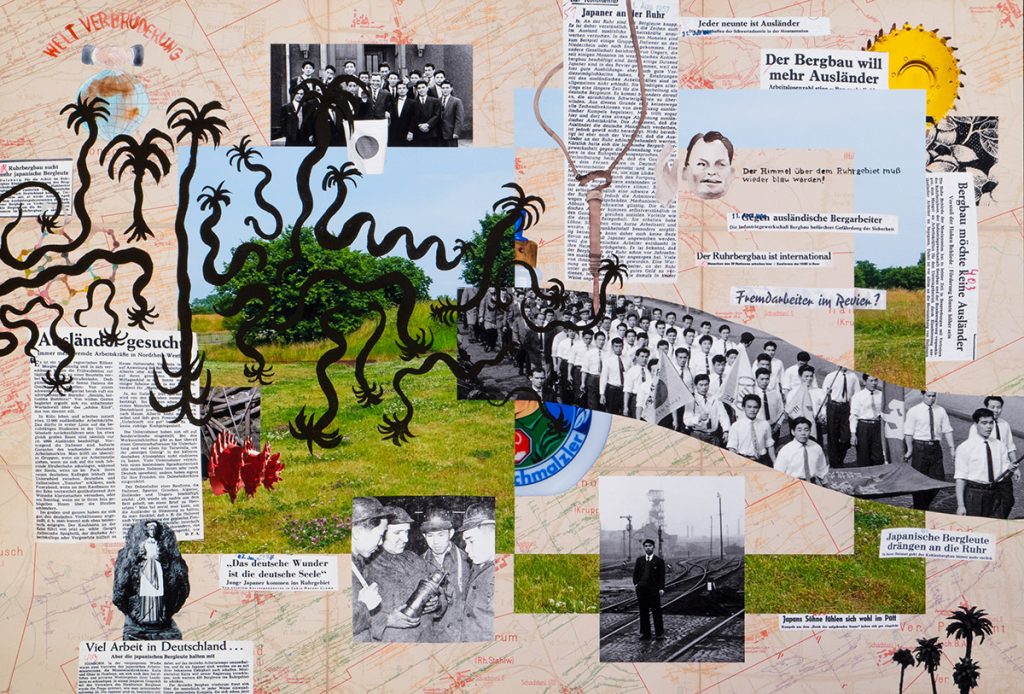

In Kawabe’s case, she declared that she wanted to dive into research before thinking about the work to be produced. She emphasized first seeing places and things in the flesh, and gathering oral testimony. We traveled to the Ruhr region, where we visited museums and the remains of coal mines; interviewed former coal miners and their families; spoke with former coal workers who administer local archives; and found many newspaper articles, notes and unpublished articles in these facilities. In Kawabe’s research report, she wove together her own words with newspaper headlines and other words from texts that emerged in the course of research. It was as if she was diving into the past, and breathing together with it. Former coal miners told us things that completely went against our own preconceived ideas; one said, with pride, “I can only remember fun times.” Noting this, Kawabe said:

Perhaps there are only a few people who have found positive experiences in the labor of coal mining. Many people have passed away before they could share their own experiences, and it is also difficult to learn about those who came to work in German mines voluntarily. Far more remains unsaid than what has been spoken—and even then, some of what has been spoken has not seen the light of day. [ 7 ]

Factual accounts cannot capture the fluctuations of experience. Here, what is required is something like the power to imagine that which did not exist. Unlike academic research grounded in documents, this suggests a realm of possibilities that could have been. [ 8 ] Turning our ears to oral history, we experienced a multiplicity of historical times, or what might be called a series of “variations” that could not be ordered into a single line of thought. Experiencing the past, multiple voices come to sound like a polyphony. If something of Kawabe herself appears in the words that are woven together here, perhaps it would be in the attitude of synchronizing with past times, experiences, and sensations, listening to unheard voices, and striving to give them form.

Kawabe’s work Japaner im Revier (2023), produced after this research was finished, combines photographs, snapshots taken in the present day, geographic documents, newspaper articles, and drawings as a multi-layered collage. Perhaps it could be called a multi-layered representation of her experience synchronizing with the past and present of Japanese people of the Ruhr coalfields. Various times flow through the Ruhr region, and various lives are there too. Kawabe collects experiences one by one, synchronizes them, and in this way shows many variations of life.

Naho Kawabe, Japaner im Revier I, 2023

Plurality as Invitation

Cobbling together a number of different methods, this project has taken an eclectic approach to the representation of historical and social research through language and visual representation. The significance of this pluralistic method might be that it opens up new possibilities of participation.

In the course of our research, we also spoke with family members of former coal miners. What arose in these conversations was that some of the women who married coal miners had studied nursing or medical care in Japan, and went to Germany on their own during the 1960s—after which point they met their spouse. We also heard the testimony of many other Japanese people who came to Germany for a variety of reasons, and who took pride in dedicating themselves to their work, paid or unpaid. Through such encounters, we learned that many people made their living in the shadow of the colossus that is the coal mining industry. It might be said, then, that countless numbers of people crossed the ocean with nothing more than the “personal asset” of work. In that sense, our research has hardly concluded with the exhibition of Kawabe’s work and the present publication. On the contrary, we intend to continue exploring various personal histories, and making them more accessible to the public. [ 9 ]

“Japaner im Revier: Aufbruch ins Fremde” encompasses lives that are not recorded in the grand narrative of history—those of us who live both in the past and the present. This project, which began with an exploration into the traces of Japanese coal miners, aims to become a space that includes the variations present among us “border crossers,” going beyond time and space, and navigating various boundaries such as gender role, profession, and social worth. Perhaps through this pluralistic approach, which invites complexity in as a constitutive part of its method, art could somehow contribute to depicting how the world is.

“Japaner im Revier: Aufbruch ins Fremde

(Japanese People in the Ruhrgebiet: Border Crossers)” at the Japan Cultural Institute (the Japan Foundation) in Cologne, 2024 ©︎studio pramudiya / npi

1. Julia Kristeva, Étrangers à nous-mêmes. Paris: Fayard, 1988, pp. 30-31. Translation from French by the author.

2. ibid., p. 32. Translation from French by the author.

3. In Japanese, see Hiromasa Mori, Doitsu de hataraita nihonjin tankō rōdōsha: rekishi to genjitsu. Kyoto: Horitsu Bunka Sha, 2005. In German, see Atsushi Kataoka, Regine Mathias, Pia-Tomoko Meid, and Werner Pacha, eds., Japanische Bergleute im Ruhrgebiet “Glückauf” auf Japanisch. Essen: Klartext-Verlag, 2012.

4. Naho Kawabe, Japaner im Revier, Booklet B. Hamburg: Self-Published, 2023, p. 13.

5. Shunsuke Onaka (Calamari Inc.) was the graphic designer for Kawabe’s booklet Japaner im Revier. These concepts come from the linguist Ferdinand de Saussure; see Ian Buchanan, A Dictionary of Critical Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

6. On this topic, see Claire Bishop, “Information Overload,” Artforum #61-08, April 2023. Bishop’s article deals mostly with the development of digital technologies in art from the 1990s onwards, and the question of how artists present this research, often through excessive displays of information. The research that Kawabe and I carried out for this project, through interviews and fieldwork, might be thought of as being somewhat closer to sociological history. Although the present project is carried out under the name of an artist, the booklet that was published does not contain fiction.

7. Kawabe, Japaner im Revier, Booklet B, p. 55.

8. Artistic research often emphasizes the qualitative over the quantitative. As a result, it may contribute more to something like “expanding the realm of possibilities” than to “accumulating facts.”

9. On September 7, 2024, a public symposium will be held at the Japan Cultural Institute (the Japan Foundation) in Cologne. Panelists will include Regine Mathias (Vice President, Centre Européen d’Études Japonaises d’Alsace (CEEJA)), a specialist of German-Japanese labor history and an editor of the 2012 volume Japanische Bergleute im Ruhrgebiet “Glückauf” auf Japanisch, and Kae Ishii (Professor, Faculty of Global and Regional Studies at Doshisha University, Kyoto), a labor historian specializing in gender.

In 2022 and 2024, this project was funded by grants from the Toshiaki Ogasawara Memorial Foundation. In 2024, it was also supported by the women’s empowerment organization Zonta Club of Tokyo I, Zonta International. We express our deep gratitude for their support.

(English translation: Daniel Abbe)

All rights reserved ©︎ Naho Kawabe