A landscape hunter—for now, this is how I will refer to Noriwaki Miyamoto, a copperplate engraving artist, born in 1940. He solely focuses on walking around old town streets, both inside and outside Japan. He turns his whole body into a highly sensitive receiver. He particularly likes narrow alleys, like the ones that are scattered about and that expose the truth about towns. He captures the rich scent of life drifting by. He imprints the subtle harmony of light into his mind. He perceives the unseeable flow of time.

The elements of the landscapes he has perceived are dismantled into the five senses—seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting and touching—which are individually placed inside the sack of his memories. Those elements then undergo a maturation period over an extended period of time.

When would those elements be retrieved from the sack?

No one knows, not even the artist. The landscape he saw is sublimated into a work of art, after the five senses have been intermingled within him, and then is “simplified, modified and accentuated” by the artist.

This might take ten years or even twenty, before the landscape in his memory that has been transformed through his imagination appears in the form of a print work. Thus, one can only say the moment is born out of spontaneity.

.jpg)

Town’s Memory(1),2002

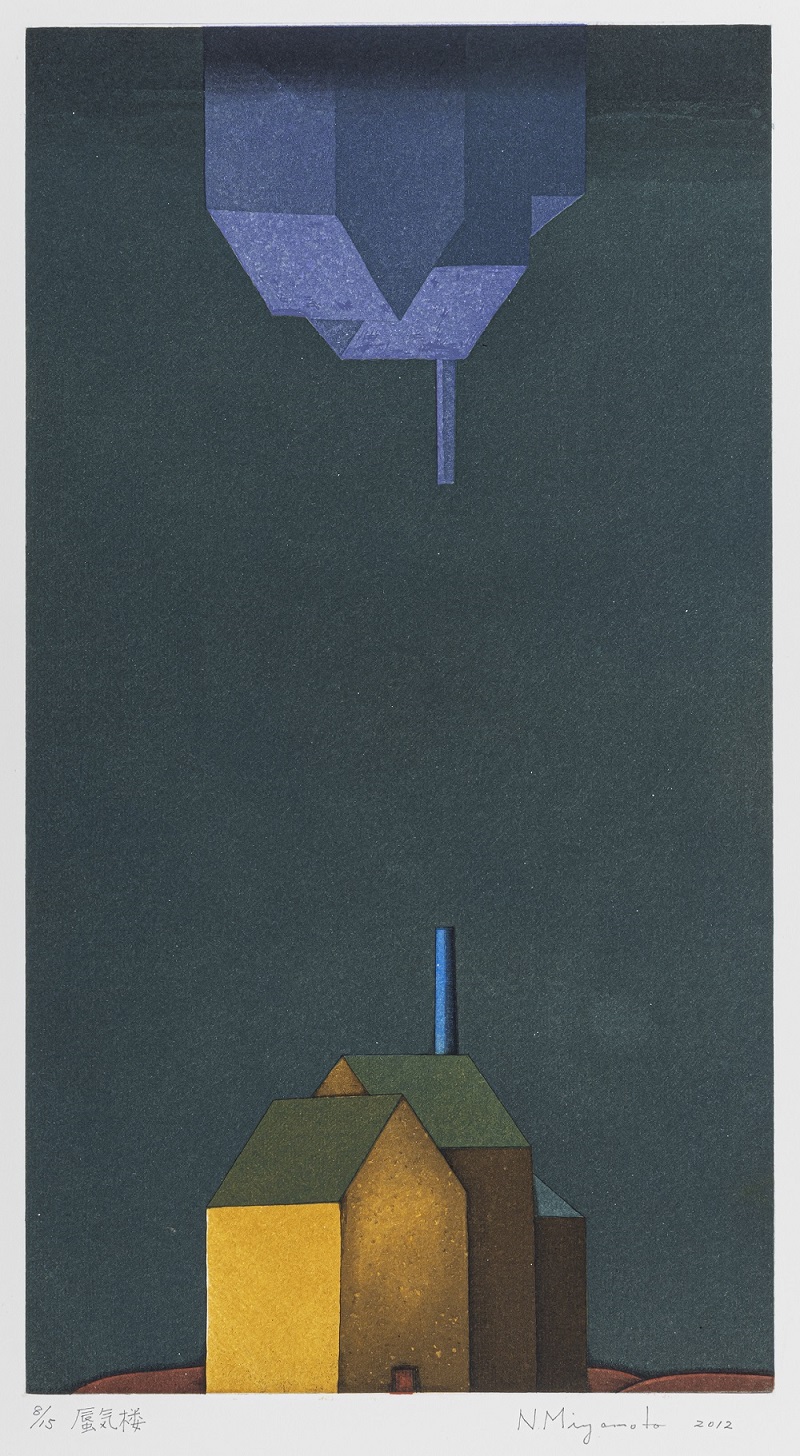

Since 1999, he has utilized the aquatint technique to produce his “house series,” in which buildings are overlapped. His initial works were mostly in black and white, but in recent years, they contain many colors.

Nonetheless, the most distinctive characteristic of Miyamoto’s art from the initial stage has consistently been the ingenious way in which he converts a town’s own memory— that is, the “memory of a landscape” into his own memory.

Aquatint, one of the techniques of copperplate engraving, has long been his choice of production method.

If etching expressed with lines were to be seen as taking the “primary” role in copperplate engraving, then aquatint expressed with planes would be considered a “secondary” role. Interestingly, Miyamoto has purposely adopted planes to serve the main role in his works, which would normally remain in the background.

Lines are annoying since they take a “me, me, me” attitude. But Miyamoto has daringly expressed a controlled lyricism, through engaging only with the use of homogeneous and flat color-fields.

From this expression, one can strongly feel the influence literature has had on him. Namely, Kunio Ogawa’s (1927–2008) book Aporon no shima (Isles of Apollo), which he first read in his youth, has continued to greatly influence him.

During the years Ogawa was a student at the former Shizuoka High School, he was immersed in creating oil paintings in the school’s art club. He studied painting theory under oil painter Ichinen Somiya. Without losing his aptitude for painting throughout his lifetime, Ogawa pursued the passage to literature.

Miyamoto reflected on the reason why he was devoted to the novelist Ogawa, and stated, “I liked his detached way of writing that simply followed what lay before his eyes, as if he were pushing away the readers.”

Mirage,2012

In discussing Miyamoto’s adopting of the “secondary” role of aquatint and planes, one could say that Ogawa’s strong influence on him could be seen in the way he has continued to exclude “adjectival” depictions from his own works.

Miyamoto is unique in that he has conveyed a sense of beauty without ever using any adjectival expression of “beauty.”

An approach he frequently takes in order to confirm the outcome of his own work is determining:

“Whether I can go into the town I created.”

Not merely to enter into the town—rather, for him to weigh with a levelheaded mindset whether he can walk around inside the town. And to make sure that the viewers are able to perceive the alley that extends into the depth of the work, while also sensing the presence of people there in that alley.

Miyamoto is also a sound hunter. His ears love music from the depth of his heart. He has been devoted to music since his youth, to the extent of saying, “If I had bigger hands, I would have wanted to become a guitarist.” He is fond of all genres of music. He enjoys any music, including classical, fado and tango.

Generally speaking, painting (or print work) is referred to as spatial art, and music as temporal art. But in actuality, we sense time through viewing a painting, while also perceiving spatial expansion through listening to music. If we were to continue gazing at a painting, such an interaction between time and space would take place.

In Miyamoto’s case, time and space easily mingle, for he tends to be “synesthetic,” which allows him to see colors from sounds, and hear sounds from colors. This is probably the reason why the viewers can also perceive “music that has crystalized in the form of colors” in his works, or else perceive “colors that morphed into music.”

The genre of music he is particularly fond of is a form of Portuguese folk music called “fado.” Fado, which was born in the early 19th century, has continued to captivate people with “saudade,” a Portuguese term which has various translations, including melancholia or profound nostalgic longing. And one of the literary figures Miyamoto admires is Portugal’s national poet Fernando Pessoa (1838–1935), who valued the pathos delivered via saudade and fado.

I almost felt as if Pessoa’s poem Some Music was a work that was written by Miyamoto. I would like to introduce this poem, which was translated from Portuguese by writer and translator Richard Zenith.

Some music, any music at all,

As long as it casts from my soul

This uncertainty that longs

For some kind, any kind of calm!

Some music—guitar, violin,

Barrel organ or accordion…

A quick, improvised melody…

A dream in which I see nothing…

(Fernando Pessoa & Co.: Selected Poems, Fernando Pessoa, ed. and transl. by Richard Zenith, 2022, Grove Press)

Another distinctive feature of Miyamoto’s works is that the viewers would not have the faintest idea about the nationality or the gender of the artist by just viewing them.

Upon reflecting on the many years Miyamoto has shown his works in public, he stated:

It is really strange, but while the viewers from abroad commented on my works as being “Very Japanese,” I have heard many Japanese viewers say, “I thought the works were by a foreign artist.” These responses might be because my works fuse the East and West within a single print.

Whether Miyamoto’s works that have unified the East and West are created by a man or woman remains an unknown. Nor can the viewers determine whether his expression is from a thousand years ago or thousand years from now.

Without being affected by the passage of time, his works always maintain a sense of newness—in other words, they are wrapped in a timeless atmosphere.

Artworks that are being developed anywhere in the world today, not just in Japan, heavily emphasize an attitude that values social fairness, justice and diversity. So much so that at times, artworks seem to have degenerated to becoming tools for political conflicts.

The apparent uniqueness of his expression is that without leaning toward such a trend, Miyamoto has consistently pursued a borderless, creative activity through using a single methodology: “the intermixing and maturing of the five senses.”

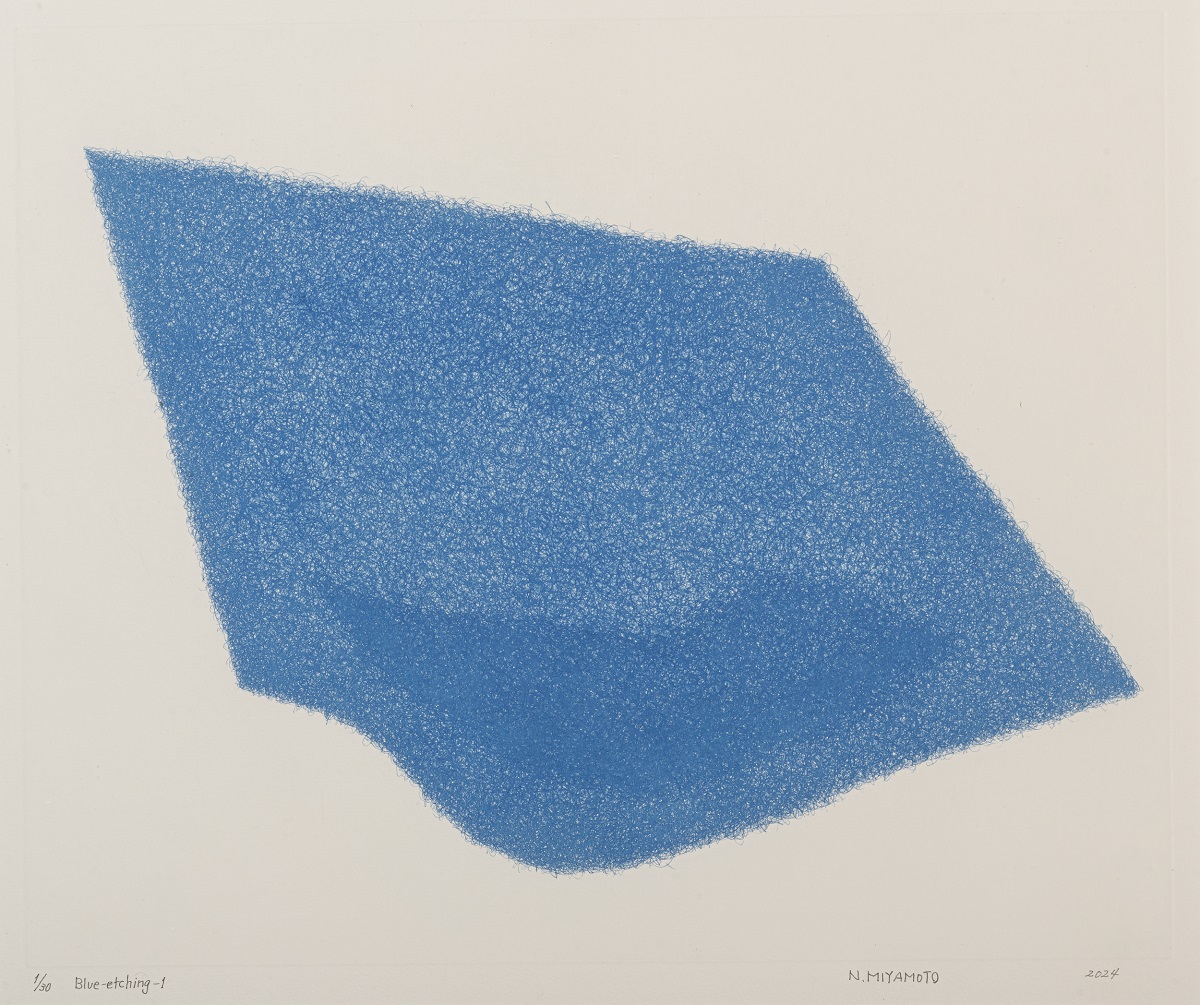

Blue Etching-1,2024

A notable new trend is found in his latest works. In recent years, Miyamoto has been engaged in creating prints using only “etching,” which is the most basic technique of copperplate engraving.

However, his works are totally different from the elaborate and delicate style of small-sized prints, which people might conventionally recall from the word “etchings.” In his works, from within the expression of irregular planes, like a “stain” stretching boundlessly, there hazily emerges the sight that has been drawn out from his memory.

Instead of showing lyricism in a direct way, he indirectly (that is, as a “secondary” role) reveals the theme he aims to depict. This level of ingenuity that he has demonstrated is unrivaled compared to any other artists. I anticipate that many more intriguing works by Noriwaki Miyamoto will continue to appear, through his new development centered on etching.

(English translation: Taeko Nanpei)

-1-1000x426.jpg)