Fig. 1 Daiki Nishimura, Beginning rain on the gravestone, 2023.

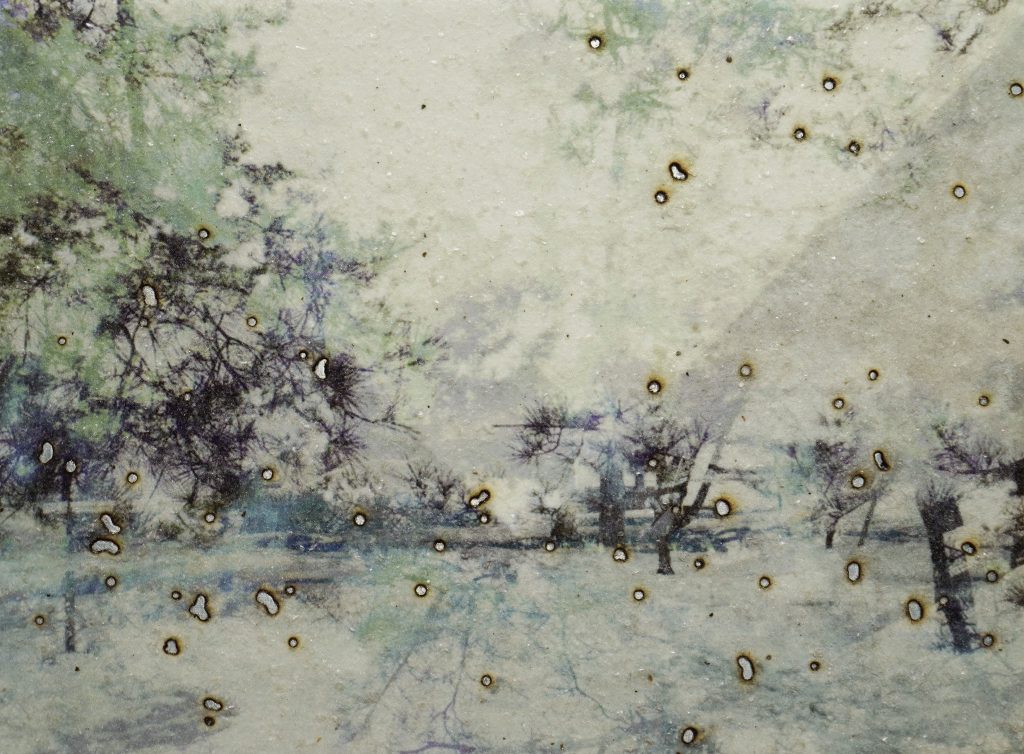

Fig. 2 Daiki Nishimura, Like a cloud after a lot of rain, 2023.

Daiki Nishimura’s oeuvre is pure, serene prayers filled with light.

One must closely examine his series of small works entitled “Record” to fully appreciate Nishimura’s mastery (Fig. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6). At first glance, the pieces appear to be abstract paintings. However, as one approaches, they transform into ink-wash representations of a pine forest. Further scrutiny reveals that they are, in fact, mixed media compositions utilizing photographs. The framing of these landscapes skillfully reflects the boundary between the objective external world and the subjective internal realm. Consequently, although the images are devoid of human figures, they retain an indelible sense of the photographer’s presence within that moment and space.

According to Nishimura, his creative process commences with photography. He captures the essence of the natural scenery he traverses, experiencing light and wind through the lens of his camera. The image is then fixed onto photographic paper, and with the use of a solvent, is slightly raised and blurred. Subsequently, small holes are punctured into the image using burning incense. The final stage involves affixing the image to a matte aluminum plate and finishing the surface with crystalline powder. The resulting image is enveloped in warm, ethereal hues of blue and green, subtly emitting a delicate luminescence and appearing to undulate with the semi-transparent, semi-abstract motifs depending on the viewer’s angle. This photographic yet ambiguous image possesses the ability to gently enliven the imagery, fostering a sense of familiarity and intimacy for the viewers while simultaneously avoiding the constraints of a fixed representation. The long, obscure titles, which seem to whisper something personal, further enhance this intimate connection without imposing limitations on the viewer’s interpretation. Nishimura’s style, honed through a decade of experimentation and refinement, is deeply rooted in his unwavering individuality. Thus, at first glance, it may seem as though anyone could attempt this feat, yet it is improbable that another’s work would radiate the same captivating brilliance. This is because within the creator’s ingenuity lie his own poetry and truth.

Fig. 3 Daiki Nishimura, The scenery seems to be seen for the first time from the white space, 2023.

Fig. 4 Daiki Nishimura, Somewhere music and moonlight are one, 2023.

Nishimura is among the contemporary painters who are conscious of environmental issues. His father, an ornithologist and environmental assessment specialist, profoundly influenced his artistic outlook. When he was a mere three years old, a tragic accident rendered Nishimura’s father paralyzed for nearly 20 years. Nishimura remained steadfastly by his father’s side, not only inherited his profound love for nature from his father but also deeply learned the invaluable significance of daily peace and tranquility. It is worth noting that the passing of his father served as a major catalyst for Nishimura to earnestly address environmental concerns within his artistic practice. With such a background, Nishimura often laments the fact that all rainwater on Earth now contains chemical substances, rendering it unsuitable for drinking. He acknowledges that the world is already polluted and maintains a persistent intention to seek ways for humanity to survive in this context. Rather than conveying environmental issues from a moral standpoint, Nishimura is convinced that, as a painter and artist, there must be more accessible forms of expression. In doing so, he remains committed to carrying on his father’s aspirations as a scholar and practitioner. By presenting captivating images of pristine natural beauty that inspire a sense of longing in people, his “Record” series embodies this aspiration.

Fig. 5 Daiki Nishimura, All I can see are scammers looking for ducks, 2023.

Fig. 6 Daiki Nishimura, The morning begins from the spider’s thread, 2023.

Initially, Nishimura drew inspiration from the landscapes surrounding him. However, his relentless pursuit of the ideal artistic representation led him to Amanohashidate in Kyoto, one of the “Three Great Views of Japan,” revered for centuries by the Japanese. Amanohashidate is a 3.6-kilometer-long sandbar that stretches across the mouth of the bay. Over 5,000 pine trees adorn the sandbar, encapsulating the quintessential Japanese coastal beauty characterized by “white sands and green pines.” Each work in Nishimura’s “Record” series features the pine groves of Amanohashidate, which he has personally walked through and captured with his own lens. Amanohashidate appears in mythology due to the uniqueness of its natural terrain that evokes a sense of grandeur and mystery of nature. In Japan’s oldest mythological text, the Kojiki (712 AD), Amanohashidate is described as a scaffold for the divine couple who created the Japanese archipelago from the heavens. In ancient legends, it is said to be a fallen ladder used by the deities to travel between heaven and earth. Thus, this sandbar has long been considered a sacred place connecting the “other shore (eternal world)” and “this shore (present world),” rather than merely a tourist destination.

Furthermore, Amanohashidate has been depicted in paintings since ancient times, due to its stunning scenic beauty. The most renowned piece is the “View of Amanohashidate” (circa 1501) (Fig. 7) by Sesshū, often hailed as the progenitor of Japanese ink painting. This work distinguishes itself not only as one of the earliest instances of capturing an actual landscape, rather than merely replicating a template, but also for its masterful integration of multiple perspectives within the composition, thereby bestowing an artful enhancement to the scene. Additionally, pine groves are often depicted in Japanese ink paintings, with the pinnacle of this genre, Hasegawa Tōhaku’s “Pine Forest Folding Screen” (16th century) (Fig. 8) This work is renowned not only for Tohaku’s refinement of Mokkei’s Chinese Southern Song style to suit the Japanese landscape, but also for being created during a period when the artist was disheartened by the untimely passing of his beloved son.

Fig. 7 Sesshū, View of Amanohashidate, circa 1501.

Fig. 8 Hasegawa Tōhaku, Pine Forest Folding Screen, 16th century.

In this context, Nishimura’s “Record” series can be seen as a contemporary expression of the traditional Japanese view of nature. In ancient Japan, powerful manifestations of nature were believed to be inhabited by divine forces, with evergreen pines in particular revered for their longevity and considered as sacred vessels for the deities. The reason Japanese perceive divinity within pines stems from their belief that nature is deeply rooted in “the other shore” or “higan,” which is also referred to as the “root country.” This primordial realm governs not only the death but also the rebirth of all life forms. Thus, since ancient times, the Japanese have not only appreciated the aesthetic beauty of pine trees but also embraced them as symbols of hope representing the immortality and regeneration of all things. In capturing this essence, the monochromatic ink painting technique proved to be exceptionally well-suited for conveying the sublime spirituality of the subject matter. Nishimura himself has stated that he was not particularly conscious of Sesshū or Tōhaku while working on this “Record” series. Instead, he professes a strong admiration for American painter Ross Bleckner, who aesthetically represents social issues. However, this unconscious reflection of traditional sensibilities and the artistic traditions, such as Sesshu’s idealized depiction of real landscapes or Tohaku’s adaptation of foreign styles, is contemporarily expressed by Nishimura through photographic manipulation and references to Western art.

Fig. 9 Daiki Nishimura, Someday I will be able to look out the window even though it is not a rainy day, 2023.

Fig. 10 Daiki Nishimura, The messengers of the night fly away in search of food, 2023.

Fig. 11 Daiki Nishimura, They whisper to the day they walk away, 2023.

As an extension of the “Record” series, Nishimura has developed the “Foresight Dream” series (Fig. 9, 10, 11, 12, 13). In these large-scale works, which utilize a combination of oil paints, acrylics, and mineral pigments, the pine groves of Amanohashidate continue to serve as the central motif. According to Nishimura, although the motif remains the same, there are temporal and spatial differences in the production process between the two series. In other words, as oil painting takes longer than photography, each brushstroke becomes imbued with more intense emotions. Furthermore, as the scale of the artwork increases, viewers feel more enveloped within the piece, allowing for a deeper resonance with the messages emanating from the artistic world presented. What is most distinctive about the “Foresight Dream” series is the multiple vertical streaks of paint that appear to drip down the entire canvas. These raindrop-like streaks, reminiscent of rain beating against a window, have their origin in the wildfires that occurred in Australia at the end of 2019. As Nishimura watched news coverage of the forest fires, he humbly acknowledged that such large-scale conflagrations could no longer be extinguished by human efforts, and instead, reliance on long-term natural rainfall was the only viable solution. Similar to the COVID-19 pandemic that began in 2020, various infectious diseases arise due to human-induced changes in ecosystems. The overwhelming power of these uncontrollable plagues leaves humanity with no choice but to wait for a natural resolution. The quiet yet hopeful images of the “Foresight Dream” series, which evoke a longing for the light of dawn, seems to wordlessly remind viewers that instead of arrogantly believing we can control nature, we should live with a sense of gratitude for being “loved and sustained,” never forgetting our reverence for the natural world.

The gentle morning sun heralds the start of a new day. The sunlight envelops a tranquil afternoon with a comforting warmth. And within the modest, peaceful routines of everyday life, we catch glimpses of eternal moments. In Nishimura’s works, there is an abundance of hope and prayers for tranquility and purification.

Fig. 12 Daiki Nishimura, I have to wear boots

and walk alone with a cold illusion, 2022.

Fig. 13 Daiki Nishimura, Until we blend in with the world, 2021.

- Sesshū (1420-1506): A painter and monk. After Sesshū studied painting and Zen Buddhism in Kyoto, he traveled to China to hone his skills by learning from the ancient paintings of the Song and Yuan dynasties, as well as the latest artistic trends of the Ming dynasty. Upon returning to Japan, he traveled extensively, devoting himself to sketching from life and breaking free from the imitation of Chinese paintings to establish a uniquely Japanese style of ink painting. His works had a profound influence on future generations. Among his many accomplishments, six of his works, including “View of Amanohashidate,” hold the distinction of being designated as Japan’s National Treasures – the highest number for any individual artist.

- Hasegawa Tōhaku (1539-1610): A painter who was influenced by the ink paintings of Mokkei and Sesshū, and claimed himself to be the fifth-generation successor of Sesshū. Tōhaku thrived in Kyoto during the Warring States period, and his artistic prowess quickly earned him the admiration of contemporary power brokers and cultural figures, leading him to the pinnacle of the art world in his own lifetime. Unfortunately, he was not blessed with a successor. His masterpiece, “Pine Forest Folding Screen,” is a Japan’s National Treasure and has been frequently chosen as one of the most beloved works of art among the Japanese people.

- Mokkei was a prominent painter-monk who flourished in the late 13th century during the Southern Song and Yuan dynasties in China. He was renowned for his mastery of ink wash painting, characterized by its ability to convey a sense of moist atmosphere. His artistic style had a considerable impact on the development of Japanese ink wash painting.

- Ross Bleckner (born 1949) is a distinguished contemporary American painter working in New York City. He is known for his unique style that seamlessly blends figurative and abstract elements, utilizing symbolic imagery to thoughtfully address pressing social issues such as AIDS

(Translated by Kazari Kanemitsu)

【Official Site】

https://daikinishimura.jimdofree.com/

*This article was produced at the request of the artist as an official commentary for his “Record” and “Foresight dream” series.