Daiki Nishimura Solo Exhibition | Absent Landscape, Peaceful Sea

Feb. 17 – Mar. 20, 2024

Open 11:00 – 18:00

Second Term

Apr. 6 – Apr. 21, 2024

Open 12:00 – 18:00 (Close on Mondays)

Paintings as the Oasis Created by a Pure Spirit

Tomoki Akimaru (Art Critic)

Daiki Nishimura was born in Osaka in 1985, and he has received a huge influence from his father who engaged deeply in the establishment of Osaka Nanko Bird Sanctuary. His father worked in the research of impacts on environments by innovations. However, when Nishimura was three, an unexpected accident left his father severely disabled and could not leave a bed for twenty-years. As Nishimura came into contact with his father’s physical disability but constant positive and free spirit, he realized that he had inherited his father’s love for nature and how important water is for the existence of life.

Nishimura then became a painter. The death of his father and the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011 prompted him to focus on the themes of climate change, radioactive pollution, and other environmental issues facing current society. This is probably because Nishimura believes that painters have the power to move people’s hearts and change society in a different way from scientists. In other words, despite the fact that the more people speak about environmental issues, the more preachy they become and may shut others down, Nishimura believes that art has the potential to evoke what is truly important by presenting pure beauty and wonderful things.

Nishimura’s style is not vibrant, but rather plain. It is dark rather than bright. It is also somehow sad and yet very beautiful. That is why, once viewers experience his work, they cannot let go of it. In fact, a Mexican woman who had just experienced grief placed an order from overseas after seeing his work online. This may explain that his paintings strongly touch the heartstrings of those who share his sincere and delicate melancholy and sense of beauty. There is something universal about Nishimura’s paintings.

The exhibition, “Absent Landscape, Peaceful Sea,” consists of Nishimura’s new works since 2023, the “Crossing the ALPS” series and the “1-2” series, as well as his representative works, the “Foresight dream” series and the “Neo-Kuraokami : D” series. As implied by the acronym “ALPS,” which stands for “Absent Landscape, Peaceful Sea” in the English translation of the exhibition title, the two new series were inspired by concern for the ocean discharge of “ALPS treated water” that began on August 24, 2023 from TEPCO’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, which was damaged by the Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami. According to the official website of the Ministry of the Environment, “ALPS treated water” is “the water in which contaminated water containing radioactive materials has been purified and treated by a multi nuclide removal system (ALPS: Advanced Liquid Processing System), etc., until it meets regulatory standards for environmental discharge of radioactive materials other than tritium. To this news, environmental groups such as Greenpeace have raised questions about the safety aspects of this process, and the fact that various media have covered the issue is still fresh to the author’s memories.

Jacques-Louis David “Napoleon Crossing the Alps” (1802)

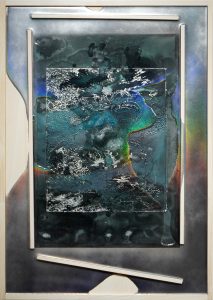

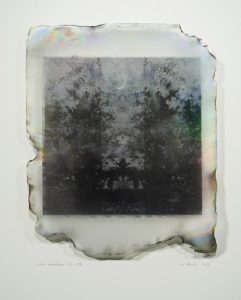

Nishimura mentioned that the word “ALPS” in such news reports reminded him of Jacques-Louis David’s “Napoleon Crossing the Alps” (1802). This famous painting from the collection of the Palace of Versailles, in which David, the court painter, exalts Emperor Napoleon as a hero, is now widely known as a kind of idealized propaganda work, since it is physically impossible for Napoleon to stand on both feet on a horse that actually stands on its hind legs, or that Napoleon was really riding a mule when he crossed the Alps. David’s “Napoleon Crossing the Alps” is a series of five works, and Nishimura also exhibited a set of five works from the “Crossing the ALPS” series at this solo exhibition. According to Nishimura, all of them were made by stretching a piece of Japanese paper traced from David’s “Napoleon Crossing the Alps” over water on a wooden panel, creating a square weir with wooden frames around the paper, placing an ice block of blue-green water-soluble paint of the same quantity and density on the paper, and allowing it to melt naturally. Then the seawater which seems to contain ALPS collected from the Fukushima sea, is poured into the ice to dilute and diffuse the water-soluble paint, and resin is poured into the ice to make it glow with a dull rainbow color using pigments. Each of the five works has a different amount of seawater from one to five cups, which makes the viewer think that the total amount of the original water-soluble paint does not change due to dilution. In any way, these works are very conceptual in which Nishimura, as a painter of his time, sincerely attempts to address current environmental issues.

Daiki Nishimura “Crossing the ALPS” series (2024)

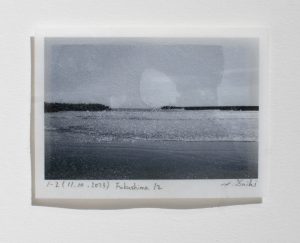

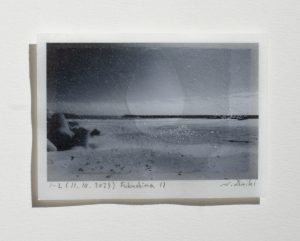

The “1-2” series, in spite of its plain title, is a series of photographs taken along the border of the area between the Fukushima Daiichi (the first) and Daini (the second) nuclear power plants, an area that is currently designated off-limits. In these works, pigment-printed photographs on Japanese paper are bonded to aluminum plates with transparent resin. The resin is applied to the center of the plate in the shape of the letter “0,” and when the resin is crimped, it is pushed out of shape, sealing in the air in the center. As a result, the outer edges of the photographs remain floating in the air and unstable, while the trapped air appears to filter through as flecks in the center of the image. The fact that the scenery that is the subject of the photographs is so ordinary and idyllic at first glance, and that we cannot enter it at the present time, makes us feel a strange sense of discomfort. Nishimura has already created another series of works using photographs, the “Record” series. In the “Record” series, Nishimura uses solvent to make a faint haze over photographs of landscapes taken by himself, makes small holes in the surface of the photographs, mounts them with an aluminum plate, and applies crystallized powder on the surface to make the entire image appear nostalgic and glowing. When the author asked Nishimura why he did not produce these photographs from “1-2” series as part of the “Record” series, he answered that he had thought of doing so at first, but while the “Record” series extracts the essence of natural scenery and aestheticizes by adding work, he could not think that he could change a thing about the landscapes of the area or process them, so he created them as a separate series. Then, the author asked him again why he applied the resin in a “0” shape. He replied that it had two meanings: “ground zero,” indicating the hypocenter, and another one is the wish to “return what happened to zero”, but in the end it was crushed and lost its shape during the crimping process, both “zeros” also expressed a sense of helplessness that he had no control over. In the exhibition space, a video of the “1-2” series was projected in the form of a reference exhibit, showing scenes from the production of “Crossing the ALPS” mixed with scenes of Nishimura actually taking those photographs. From watching Nishimura standing and pumping seawater in the deserted and “absent” landscape of Fukushima, it is obvious that he was seriously and physically facing this theme.

Daiki Nishimura “1-2” series (2023)

The “Foresight dream” series shows several changes in impressions of images compared to the past works. According to Nishimura, the series was originally inspired by his research on outbreaks of infectious diseases such as the COVID-19, and his surprise when he learned that one of the causes was the increased contact between wild animals and humans due to ecosystem changes caused by over-forestation and excessive land development. Another source of inspiration came from his sadness from knowing that the massive wildfires that have recently been happening in the Amazon, Australia, and other parts of the world which cannot be stopped by human power any longer, and can only be extinguished by long-lasting, disaster-grade flood. Both of these realities foreshadow the apocalypse of the end of the world, and inspired by them, Nishimura has created a series of works that depicts the reality of the hopeless future. However, even though his past works often display the image like raindrops moving down a window in the dark night from inside a room, the glowing resin film covering the images expanded greatly, and the landscape in the background changed from almost completely abstract to more figurative with more colors and brighter colors. When the author asked about feelings on this change, Nishimura said that the resin in this series has a strong awareness of rain, but rain does not just fall vertically; it changes in various ways, such as condensation and puddles. Therefore, in this “Foresight dream” series, too, he wanted to transform the shape of the resin film in various ways and pursue its potential as a series of works. In this process, he made the underlayered image more objective to keep up with the strong materiality of the resin as it is expanded and added, and he chose bright colors for the under layers to balance the stronger light reflection and iridescence. However, the author’s own thought is that the restoration of figurative expression and the use of a wide variety of colors reflect to some extent the slightly cheerful mood of the time when the COVID-19 was over and people were able to go out with ease.

Daiki Nishimura “Foresight dream” series (2024)

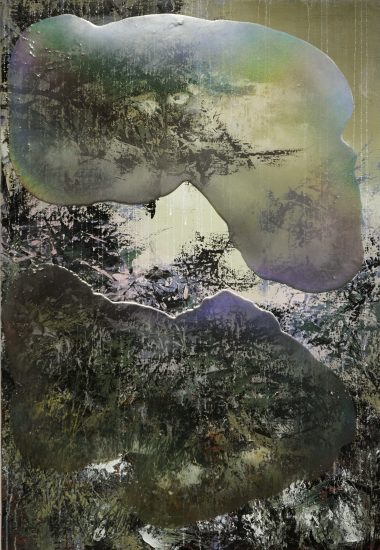

The “Neo-Kuraokami : D” series is created in the setting that “Dark God of the Water”, a water god from old Japanese mythology such as Kojiki and Nihonshoki, has been transformed into another imaginary god called “Neo-Kuraokami” due to excessive activities by human. According to Nishimura, the background to this is no land that is not contaminated by mankind exists on the earth, and when a scientific paper was published in 2022 stating that all rainwater in the world contains fluorinated surfactants (PFAS), which are known as “forever chemicals” and are not suitable for drinking. The series also reflects the sense of disappointment that Nishimura felt when the scientific paper was published in 2022, stating that all “forever chemicals” (PFAS) were not suitable for drinking. The series was also inspired by Nishimura’s witnessing a beautiful rainbow in the sky after an evening shower while chemical colored cloud patterns blurred the puddles of asphalt on the ground, and he discovered a snarky contrast between the natural and the man-made. This series aims to create a kind of “contemporary landscape photography” on the theme of water which is necessary for human existence and its pollution. That is why Nishimura has been processing photographs of water-related landscapes such as rain, snow, clouds, and waterside, and using glowing resin and iridescent paint to accentuate the changes, thereby attempting to reveal the nature that is being transformed as a result of human activities. Specifically, starting from the same photographic process as in the “Record” series, he creates a symmetrical image by layering the same image on top of it, inverted, and spreading resin over the top of it to the point where it overflows, while also using pigments to create a dull rainbow-colored glow. The cracks in the resin created during processing are also part of the concept that shows traces of human manipulation. The word “okami” is an archaic term for the dragon which is the god of water and rain. For Nishimura, “Neo-Kuraokami” is an image of a mollusk like a jellyfish or slime that has been altered by chemical substances, and the resin protruding from the image, a prominent feature of the series, was created with this in mind. The “D” in the series name came from the initials of DuPont, a well-known fluorosurfactant manufacturer.

Daiki Nishimura “Neo-Kuraokami : D” series (2023)

Nishimura’s explanations of his works often end with pessimistic tones. In fact, even at the celebratory opening talk event, his perception of the times was so serious and tragic that the audience sometimes turned silent. However, even if Nishimura’s words are pessimistic, the impression the author got from each of his works was somewhat different. While Nishimura’s awareness of the tense situation and his technical ingenuity as a painter are of course present, there seems to be something else in common that transcends these factors. It is a feeling of awe and a prayer towards the “epiphany of hidden great nature” on the unconscious level.

In the “Crossing the ALPS” series, the patterns of water and light that form an accidental yet inevitable pattern on the image are created by the action of nature just as the pattern that appears when pouring milk on coffee evokes the mystery of nature. In the “1-2” series, Nishimura intentionally avoids explanatory material and does not include any specific objects that indicate the destroyed areas such as flexible container bags filled with decontaminated waste. By doing so, the tranquil natural scenery in the images evokes a strong sense of nostalgia as a loss of daily life, and the patches of air that appear on the image are a reminder of the fundamental regenerative power of nature. In the “Foresight dream” series, the theme of rain, which has been pursued in this series for a long time, is both purified and yet transformed in a flexible manner, and one can sense Nishimura’s firm trust and reverence for nature, especially water. In the “Neo-Kuraokami : D” series, the same natural landscape is first layered in reverse, so that the sacredness of nature seems to be expressed in a remarkable way. Furthermore, in the sense that Aldous Huxley points out that the luminosity of gemstones reflects the beauty of the heaven, the iridescent transparent resin film brings a concrete and sensuous reality of nature (the natural cracks reinforce this), and at the same time, it seems to give us a glimpse of the beauty of the heaven, the place of circulation of death and rebirth that underlies the world in a super sensuous way.

To the author, Nishimura does not seem to be a defeatist. This is because all of his works show a healthy mind and creative will to genuinely seek and express beauty. This is true even when he is self-deprecating about the use of chemical pigments and artificial materials. This is because his use of such materials is an expression of his trust in the beauty of the natural world at a deeper level, including artificial materials. When the author asked Nishimura about this, he answered that he often ends his explanations of his own works with a pessimistic tone, but this is because people who view his works will surely sense that he is not in despair but is always holding out hope, and it feels like a waste and redundant for a painter to go out of his way to explain it in words. On the one hand, although there is an understanding that the natural world is always a survival of the fittest, and that the disappearance of one species or the creation of human artifacts is also a more profound and eternal act of nature, he also spoke of the unique optimism of the human being’s freedom to struggle against their destiny. This is the essence of the free, vibrant, and pure spirit that we perceive in the depths of Nishimura’s paintings. In any case, Nishimura himself, as a human being, is always serious and earnest in facing the theme of environmental issues. This consistently imparts a certain sense of deep melancholy to Nishimura’s paintings. Nevertheless, the author acknowledges that sadness and beauty that viewers sense from Nishimura’s paintings are not a sense of hopelessness, but a glimmer of hope for rebirth and recovery. In this sense, the series of paintings created by Nishimura as an artist that emotionally evokes the tranquil prayer and wish for “peace” that lies in every human’s heart are a breath of fresh air in current overheated society, or a kind of the oasis that gives healing and relaxing experience for people’s minds.

(Translated by Yumi Nomura)

Daiki Nishimura Official Website

https://daikinishimura.jimdofree.com/

*This article was produced for the catalogue of the solo exhibition of Daiki Nishimura, “Absent Landscape, Peaceful Sea”.