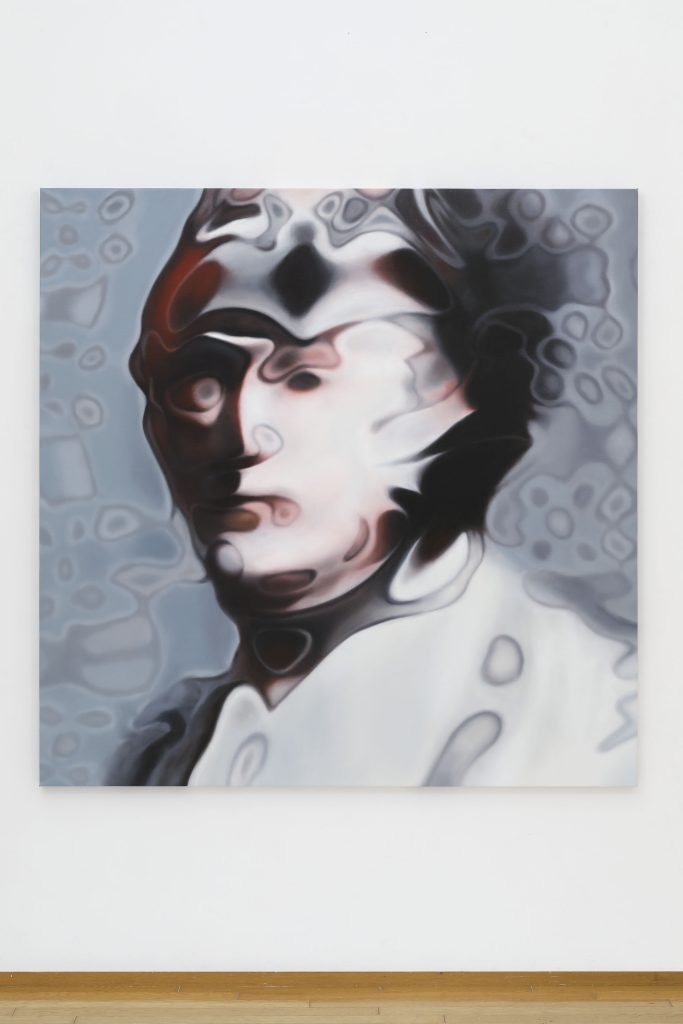

Exhibition View | Photo: Takeshi Kureta

Seishu Nihira: Phantom Paint

Dates: March 22 (Sat) – April 26 (Sat), 2025

Venue: Art Court Gallery

URL: https://www.artcourtgallery.com/

The solo exhibition of Seishu Nihira’s new works, “Phantom Paint,” is being held at Art Court Gallery from March 22 to April 26, 2025.

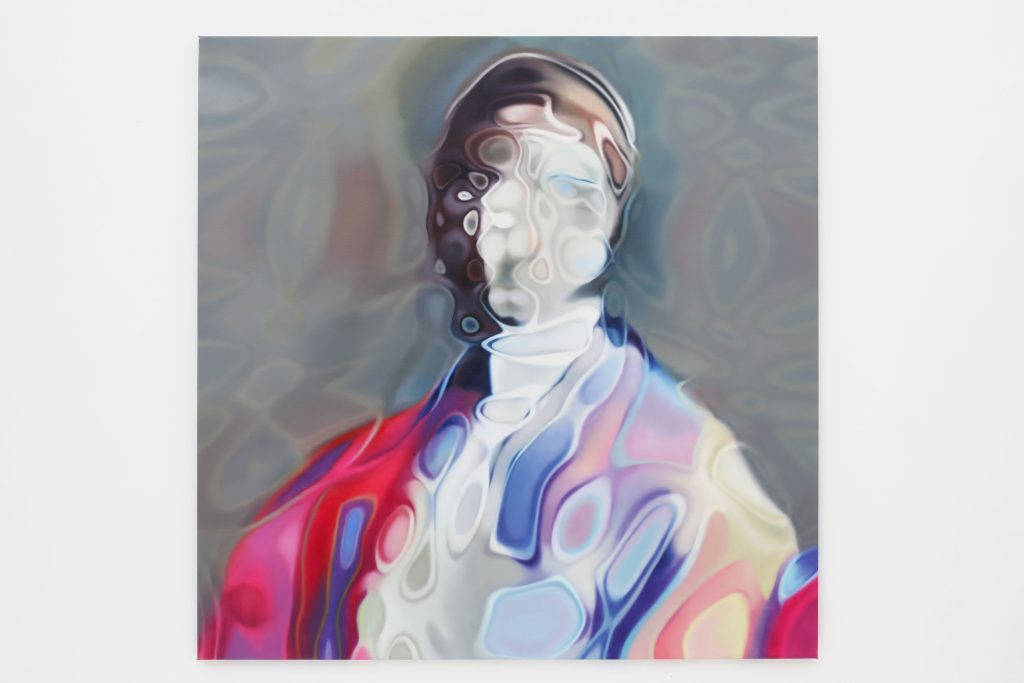

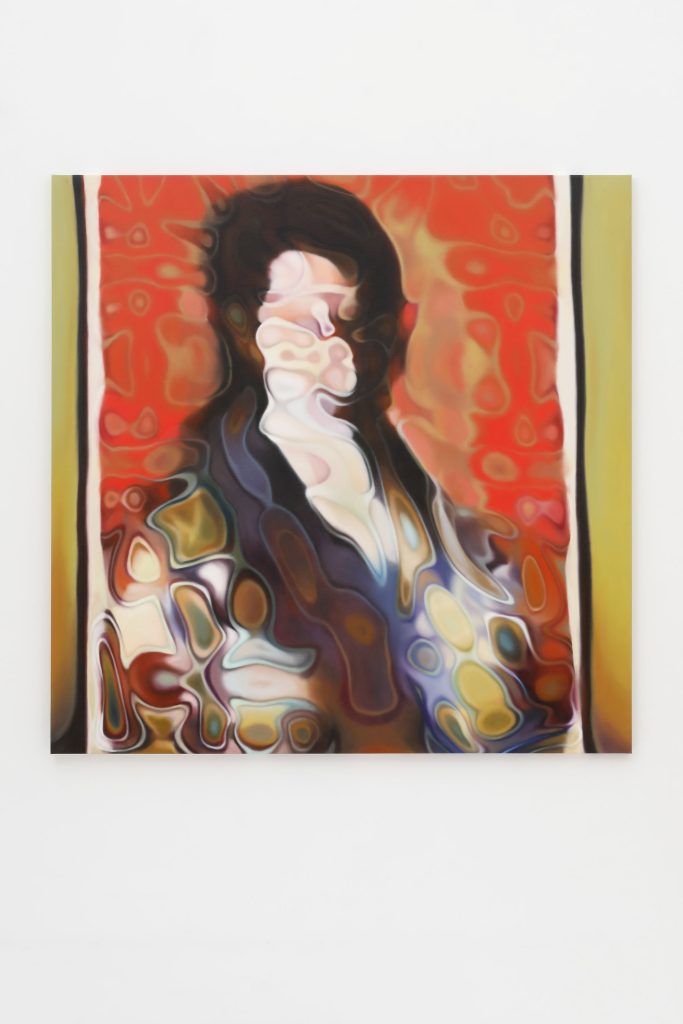

The exhibition features four large paintings and nine smaller ones. While they can just barely be recognized as “portraits,” it is impossible to discern who the subjects are. It is as if a massive aquarium has been placed over the portraits, and the images are seen through the wavering surface of the water. The liquid, possibly water or something with greater viscosity, undulates, causing the light to refract and transmit in such complex ways that the identity of the portrayed figures becomes unrecognizable. Such are the paintings on display.

Exhibition View | Photo: Takeshi Kureta

Those familiar with the rapid advancements of AI (Artificial Intelligence) in recent years might recognize that these images are based on AI-generated visuals. In this exhibition, Nihira selected portraits generated by AI at about 10% of the completion stage, choosing intuitively appealing images and then meticulously reproducing them in oil paint.

The significant influence of AI in the field of art has only emerged in the past decade. AI research, proposed by John McCarthy at the Dartmouth Conference in 1956, began in the late 1950s with a focus on reasoning and search processes, sparking the First AI Boom. However, as it could solve only simple puzzles and mazes and failed to function in real-world settings, AI research entered its first “winter.” In the 1980s and 1990s, with advances in computing power, the Second AI Boom occurred as attempts were made to create expert systems that could respond like human specialists. Yet, it was difficult to formalize vast datasets into operational rules, leading once again to a decline.

By the 2000s, with the dramatic increase in computing capacity and the accumulation of “big data” through the internet, AI entered the Third Boom, characterized by autonomous machine learning. Furthermore, the development of “deep learning” based on neural networks—systems mimicking the structure of the human brain—led to rapid improvements in AI accuracy.

Since the emergence of conversational AI such as ChatGPT in the 2020s, society itself has been undergoing profound transformation. Some even argue that the Singularity—a term coined by futurist Ray Kurzweil, referring to the point when AI surpasses human intelligence and predicted to occur by 2045—has already arrived.

In this process, Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) were developed: a deep learning architecture where a generator and a discriminator, two neural networks, compete against each other. Simply put, one network generates fake images while the other evaluates their authenticity, engaging in a sort of “cat-and-mouse” dynamic. In 2018, the Paris-based artist group “Obvious” used a dataset of 15,000 portraits from the 14th to the 20th centuries to produce Edmond De Belamy. This AI-generated painting was sold at Christie’s “Prints and Multiples” auction for $432,500, about 43 times its estimated price — an event still fresh in memory [i].

Exhibition View | Photo: Takeshi Kureta

The AI technology Nihira used for this project also employs GANs. When we now look at Edmond De Belamy, what was once praised as an abstract work appears more like a clumsy, unfinished painting. With the current capabilities of ChatGPT and related models, it would be possible to generate much more precise images.

Yet no matter how high the precision, what remains uncanny about AI is that we cannot comprehend the process by which images are generated. However, we humans, too, are unaware of how new images arise within ourselves. Dream images, for example, emerge autonomously without conscious intent. While some derive from real experiences or media such as television and film, many have unknown causal origins. Sigmund Freud, who founded psychoanalysis, interpreted such images as expressions of repressed unconscious desires, influencing the Surrealists.

Seishu Niihira, “Phantom Paint #2” (2025) | Photo: Takeshi Kureta

Various techniques like automatic writing, decalcomania, and frottage were developed to incorporate the unconscious into art. Similarly, Nihira could be said to attempt to extract the “unconscious” of AI itself. Unlike human painters, who leave traces of physical constraints and habitual gestures in their works, computers are free from bodily limitations. However, the use of computational devices and the constraints of specific datasets introduce distinctive patterns or “habits” that eventually manifest as a kind of style. Rather than being visible in the final output, this becomes clearer when, as Nihira does, the images are extracted midway through the generative process.

If you closely observe Nihira’s paintings, you notice ripple-like distortions across the entire surface, gradually condensing into more detailed forms. These ripples appear as concentric, color-dominated rings, almost resembling modules. Rather than evoking neural networks, they more strongly resemble the division of a single cell into specialized organs—akin to the imagery of pluripotent stem cells (iPS cells) differentiating into specific tissues.

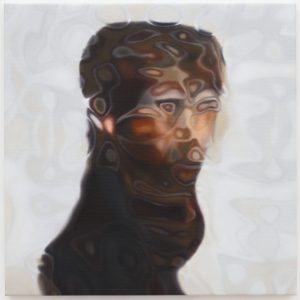

Seishu Niihira, “Phantom Paint #4” (2025) | Photo: Takeshi Kureta

Each ring-like module contains key colors characteristic of the painting. Since the dataset Nihira used likely consists of Western portraiture, the color schemes follow Western color theory, often using complementary combinations. Had the dataset been from non-Western portrait traditions, such color relationships might have looked different.

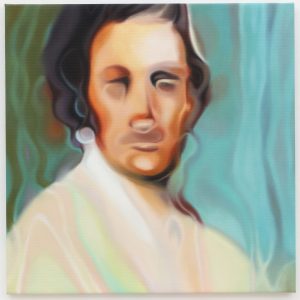

Seishu Niihira, “Phantom Paint #1” (2024) | Photo: Takeshi Kureta

Despite being captured at only about 10% completion, the human viewer can extrapolate and imagine the final portrait: for example, picturing a 17th-century nobleman painted in a court setting, or a 19th-century gentleman in a suit. However, without being told about the process, viewers might assume a completed image lies beneath a distorting filter — when, in fact, it is the opposite. What they are seeing is an initial, incomplete stage, and no definitive “answer” exists because Nihira intentionally halted the GAN’s computational process before full completion.

Yet, even at just 10% generation, the directionality of the final image is already about 80% determined from a human perspective. This suggests that in AI-generated portraits, the broader structure and atmosphere become visible very early, unlike human-made incomplete sketches, which often still feature blank or unformed areas.

AI is often called a “black box” because its internal workings between input and output are opaque. The only way to assess it is by evaluating the quality of its results. This “black box” could rightly be described as the “unconscious” of AI. Nihira retrieves this unconscious and reconstructs it into painterly information using classical oil painting techniques. Whereas digital images reduce to numerical RGB values, vivid luminous colors on a screen cannot be exactly replicated with oil paints, which have natural limitations in brightness and chroma. Thus, his works are transposed into the unique color space of oil painting. The paintings are also enlarged dramatically, evoking the grandeur of Baroque portraiture.

Seishu Nihira, “Phantom Paint #10” (2025) | Photo: Takeshi Kureta

Seishu Nihira, “Phantom Paint #12” (2025) | Photo: Takeshi Kureta

Seishu Nihira, “Phantom Paint #11” (2025) | Photo: Takeshi Kureta

Through the act of meticulous copying, Nihira may begin to understand aspects of AI’s bodiless image generation processes. By embodying this unconscious through painting, he allows it to seep into his own procedural memory — stored not in the hippocampus but in the basal ganglia and cerebellum — and retained long-term through physical action. Visual memories are, of course, also stored in the hippocampus, and the dream process during sleep helps consolidate these memories.

Exhibition View | Photo: Takeshi Kureta

When photography emerged, painters quickly realized that the profession of portrait artist would be threatened. Prior to that, optical devices like the camera obscura and camera lucida had been secretly used to trace images. But photography eliminated the need for human involvement entirely. Subsequently, painters sought ways to depict that which photography could not capture, leading to movements from Impressionism to Fauvism, Cubism, Surrealism, and Abstraction. Today, with AI, the existential value of painters, illustrators, and animators is questioned even more profoundly.

The “death of painting” has been declared many times since the invention of photography. Nihira himself was questioned during his university years about the necessity of painting — even told that there was no need to paint at all. Yet he could never abandon the joy of painting and has continued ever since. Nihira eagerly incorporates techniques and motifs from manga panel layouts, animation time expression, noise and filter effects, internet memes, and more, fusing opposing images into unified paintings, or extracting frames from videos to create sequential, photo-like paintings. By depicting different times and spaces simultaneously — something normally impossible — he creates works that prompt the viewer to actively deconstruct and reconstruct the image perceptually. And all of this, fundamentally, is simply to continue the act of painting.

In the future, artists like Nihia might cease to create their own motifs entirely, endlessly painting AI-generated images instead. To an outsider, it might appear as a dystopian scene where humans are enslaved by machines. Yet if painting were merely “labor” and “toil,” such perversion would occur. However, for Nihira — for whom painting is a joy — a machine that generates endless inspiring images could be the perfect companion.

Exhibition View | Photo: Takeshi Kureta

Now that any image can be generated by computers, is there any need for humans to paint by hand? Since prehistoric times, from Lascaux to Altamira, humanity has developed intelligence through the act of painting, an act accompanied by pleasure and delight. No matter how advanced technology becomes, there will always be forms of intelligence and joy attainable only through painting.

Just as GANs evolve through the competitive interplay of generator and discriminator networks, perhaps a new horizon will open through the rivalry between humans and computers. As computers learn from humans, so too might humans learn from AI’s unconscious processes — leading to paintings of even higher quality. From Nihira’s works, we catch a glimpse of such a future for painting, a future for the act of creating, shimmering faintly beyond the ripple-like modules.

[i] “An AI-Generated Painting Sold for $432,500, 43 Times Its Estimate,” Bijutsu Techo Online

https://bijutsutecho.com/magazine/news/market/18719

※This article was produced as an official record of Seishu Nihira’s Phantom Paint exhibition. (Photo courtesy of Art Court Gallery)