Installation view Photo: KIGURE Shinya

TANKING MACHINE-REBIRTH YANOBE Kenji in 1990s

May 29th – July 19th, 2021 at MtK Contemporary Art

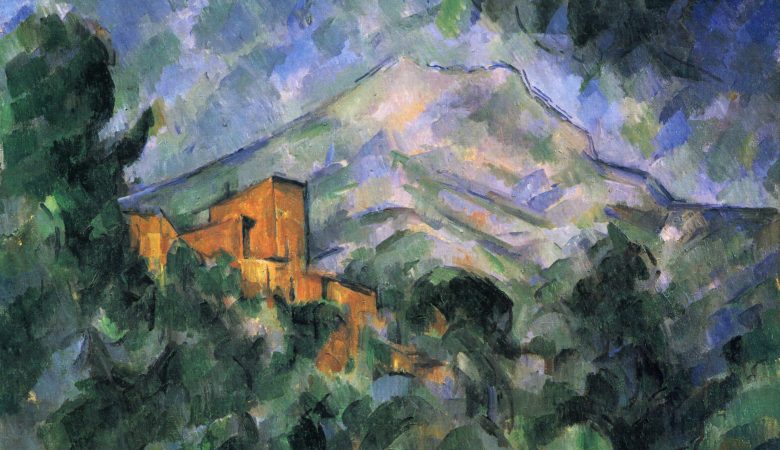

This exhibition focuses on Kenji Yanobe in the 1990s, and includes his representative works such as “Tanking Machine (Rebirth)” (2019), a reworking of his debut work “Tanking Machine” (1990), “Atom Suit” (1997), “Atom Suit Project” (1997, 1998), and “Atom Car (White)” (1998). as well as a wealth of materials such as conceptual sketches, magazines, and catalogs, to enable visitors to look back on his creative activities. The exhibition is curated thematically like a museum exhibit, and its spacing facilitates viewing it as a singular work.

The venue for the exhibition is MtK Contemporary Art, which opened this spring opposite the Kyoto Kyocera Museum of Art to the northeast, and is directed by artist Kengo Kito, who features artists that he has previously worked with, as well as personal acquaintances whose work he would like to see exhibited in Kyoto. Kyoto is home to many artists and many studios, but there are few places for artists in the middle (or beyond) of their careers to present their work, and there is an awareness of the problem that they can only be found in Tokyo galleries, overseas museums, and local art festivals. That’s why the exhibition was designed to be a place for veteran artists to show their work. It has been developed as an art project of Matsushima Holdings, the largest dealer in Kyoto, and is located next to “Smart Center Kyoto, The Garden,” Japan’s first dedicated smart store, in a high quality showroom in a renovated old house. The opening exhibition was the three-person show “Sun” by Kengo Kito, Kohei Nawa, and Daisuke Oba, and the second exhibition featured Kenji Yanobe, who was actively exhibiting in Kyoto as well as Kansai region in the 1990s.

There is no doubt that Yanobe is one of the most important artists from the 1990s. Since his spectacular debut in 1990, when he won the Excellence Award at the first Kirin Contemporary Awards, he has been active in the transition of how “contemporary art” was understood in Japan’s unique domestic context to how it was understood in a global context at the end of the Cold War. The Kirin Contemporary Award (the name and selection method vary depending on the year) is a prominent award that has produced various artists such as Tabaimo, Yodogawa Technique, and Kohei Nawa, and is also a pioneering example of corporate support of the arts.

The following year, 1991, he had a solo exhibition “An Eccentric Life of Kenji Yanobe” at Kirin Plaza Osaka, and then in 1992, he participated in the exhibition “Anomaly” curated by Noi Sawaragi at the ROENTGEN KUNST INSTITUT , and was an artist-in-residence at Art Tower Mito, where he held the exhibition “Yanobe Kenji’s World of Delusion” Around this time, opportunities for young contemporary artists to present their work at corporate gallery spaces and new museums began to increase, and Yanobe is the earliest example of this. In 1994, he moved to Berlin and joined Perrotin, which is now a prominent mega-gallery. Perrotin is also known as the first gallery to introduce Takashi Murakami overseas, and Yanobe and Murakami have alternately held exhibitions there.

Until the 1980s, most of the places where contemporary artists showed their works were rental galleries where the artists paid for the space themselves. Art Space Niji, where Yanobe had his first solo exhibition and where he presented “Tanking Machine,” was also a rental gallery. There were many rental galleries, especially in the vicinity of the Kyoto Kyocera Museum of Art and the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, where prominent artists presented their works. In the 1980s, the main route for Japanese artists to gain attention in the international art scene was to participate in the Japanese Pavilion and the Aperto section of the Venice Biennale, both of which dealt with young artists. Tadashi Kawamata, who was selected for the Japan Pavilion in 1982, and Yasumasa Morimura, who was selected for the Aperto section in 1988, are typical examples. After rejecting the typical artist’s route of the 1980s, Yanobe forged his own path in the 1990s.

In the March 1992 issue of the Japanese art magazine Bijutsu Techo, a special feature entitled “Pop/Neo-Pop” featured a discussion with Takashi Murakami, Kodai Nakahara and Yanobe, in which they introduced the trend of incorporating subculture-related fields such as manga, anime, and film special effects into their artwork. Yanobe, who was the youngest, was the earliest adapter of them all. When Yanobe studied briefly at the Royal College of Art (RCA) in 1989, he was struck by the sight of schoolchildren being lectured to in front of authentic works by masters of Western painting at the National Gallery and other venues. Then, feeling that he could not win if he fought on that playing field, he decided to incorporate aesthetics from the subcultures that he had been influenced by since his childhood.

One of Yanobe’s works, the “Tanking Machine,” was inspired by the isolation tank invented by American brain scientist John C. Lilly. The isolation tank blocks out light and sound, and by entering a floating tank of salt water kept at the temperature of the skin, the senses of sight, touch and hearing are all eliminated, and a feeling of weightlessness is achieved. In this state, the brain loses external stimuli as well as the sense of time, and will begin to daydream and enter a degenerative state of consciousness. John C. Lilly and his isolation tank were the model for the film Altered States directed by Ken Russell, which was also released in Japan and was well known among science fiction fans.

Inspired by Lilly’s isolation tank, Yanobe attempted to utilize the forms used in Japanese manga, anime, and film special effects to create a sculptural work. Since the environment of an isolation tank keeps people in a condition similar to that of a baby in amniotic fluid, the shape of the sculpture was made to look like a pregnant woman. That woman has the face of Yanobe, although it is covered by a World War II British gas mask bought at a flea market in London. Additionally, a penis-like faucet from his groin area spurts salt water. In other words, it is a sculpture that is a self-portrait of himself, both male and female. At his solo exhibition at Art Space Niji in 1990, many people entered the tank, and the work became a sensation as an unprecedented hands-on experience.

Tanking Machine (Rebirth) Photo: KIGURE Shinya

“Tanking Machine (Rebirth)” was recreated in 2019 for the 30th anniversary of the conception of “Tanking Machine,” and was shown in the “Parergon” exhibition at Blum & Poe in Los Angeles. It is slightly larger than the first generation, and has more detailed functionality, including a device that uses gas cylinders to heat the salt water inside. This time, a new gallery space has been specially added, which is visible from the street outside, just as it was when the exhibition was previously held at Art Space Niji.

Japanese post-war avant-garde art, such as Gutai and Mono-ha, has been discussed in comparison with Abstract Expressionism, Art Informel, Minimal Art and Arte Povera. As for Yanobe and Murakami, it may be possible to talk about them in terms of Pop Art, but it might be more appropriate to compare them with Tsuguharu Fujita. This is because Yanobe and Murakami, on the premise of the recognition of Japanese anime and manga that has permeated Europe and the United States, have brought their visual and figurative language into the world of contemporary art. Fujita received recognition in the world of Western painting for his “milky skin” nudes, which reproduced the unique texture of skin, based on the premise of the recognition of Japonisme that swept Europe in the 1920s with ukiyoe prints.

Moreover, it’s impossible not to mention the apocalyptic ideology that permeated Japanese subculture. This was because Tsutomu Goto’s “The Great Prophecy of Nostradamus,” published in 1973, became very popular, and its interpretation that the human race would be destroyed in the seventh month of 1999 had a tremendous impact on subculture. It is generally said to be a prophecy of nuclear war and World War III, and was a widespread theme in “Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind,” which dealt with it metaphorically, and “Fist of the North Star,” which depicted it directly. Additionally, I would like to point out that the concept of “the end of the century” overlapped with the apocalyptic ideology that focused on the year 1999, making it more frightening. In the case of Japan, the Western calendar was not adopted until after the Meiji era, and the end of the 19th century was not yet widely accepted, so the end of the 20th century was practically the first “end of the century” experienced in Japan. In other words, it was the impact of the simultaneous acceptance of Christian apocalyptic ideas at the first “end of the century”. Much of the Japanese art created at the end of the 20th century, including manga and anime, were works with themes concerning the end of the century.

After “Tanking Machine,” Yanobe created works centered on the theme of “survival” in society at the end of the century. “Yellow Suit” (1991), a radiation protective suit created in response to the Mihama nuclear power plant accident, is a typical example. However, the situation changed dramatically in 1995. While Yanobe was living in Berlin, the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake and the Tokyo subway sarin attack occurred, and what had been a matter of fiction and “fantasy” became reality. The Subway sarin gas incident cannot be separated from the “Great Prophecy of Nostradamus” and apocalyptic thinking, and many of Yanobe’s generation have confessed that there is only a slight difference between themselves and those criminals. Until 1995, there were still remnants of the bubble economy, and so Yanobe’s artwork still contained an optimistic outlook for the future. However, Yanobe’s method of production changed considerably after 1995.

In the wake of the shocks of the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake and the Tokyo subway sarin attack, Yanobe felt concerned by the fact that expression through art would become meaningless if it referred only to fictional incidents or was only exhibited in a museum. The “Atom Suit Project” (1997), in which Yanobe took a trip to Chernobyl after the nuclear accident of 1986, was organized with the idea that he wanted to see if his art would “work” in the real world by utilizing his own body as part of the piece and to see how people would react because he felt that a work of art is meaningless if it remains a delusion not grounded in reality. In order to not only prevent internal exposure to radioactive materials, but also to “feel” the invisible radiation, he created a “radiation-sensing suit” (“Atom Suit” – 1997), in which seven Geiger counters are attached to the suit, and when radiation is detected, a flash is emitted and a roar echoes.

The “Atom Suit” is an homage to the nuclear-powered fictional hero, “Astro Boy” (Japanese title: “Tetsuwan Atom,” meaning “iron arm Atom”) whose sculpted hairstyle also has two horns similar to the “Atom Suit”. Another image evoked by “Atom Suit” is that of the diving suit from the movie “Godzilla” which was created in response to the 1954 U.S. hydrogen bomb test at the Bikini Atoll, where the Japanese deep-sea tuna fishing boat Daigo Fukuryu Maru was exposed to radiation. I would like to add that the aesthetics and contexts from subcultures play a prominent role in the creation of Yanobe’s works. This is a sign that he was thinking about how to have a work of art perform a function in society.

There are not only health hazards to consider with radiation and viruses, but they are also invisible to the eyes and inaudible to the ears, so we can’t judge the danger with our senses, which is another factor that fuels our fear. For that reason, being able to make danger visible, audible, and physically felt can have a beneficial effect. If “Tanking Machine” is a device that blocks the senses and dives into the unconscious as well as dreams, “Atom Suit” is a device that amplifies reality and allows us to feel it.The “radiation detectors” were also functioning in this exhibition, and it was impressive to see the flashes glowing and the acoustics echoing in the hall when radiation was occasionally detected.

Atom Car (White) (1998) Photo: KIGURE Shinya

“Atom Car” was modeled after a go-cart that was found at a former amusement park in Chernobyl. When a coin is inserted, the car moves and background music plays from an educational animation created by the United States during the Cold War for its citizens to defend themselves in the event of a nuclear attack. But to get farther, you have to keep putting coins in, thus making an ironic statement that safety depends on wealth.

The exhibition features a series of photographs, including “Atom Suit Project: Chernobyl,” which was taken in that city when Yanobe visited while wearing his “Atom Suit,” and “Atom Suit Project: Osaka Expo,” a work taken at the site of the demolished Osaka Expo. Yanobe had played at the demolition site as a child, even naming them “Future Ruins,” which he states was his first step on his creative path. Other exhibits included drawings describing the events of his visit to Chernobyl. Changing one’s perspective via a work that can augment one’s senses and allow for expressing oneself in a real place may increase the strength of that work, but it is a double-edged sword. That is because exhibiting a work in public can be more risky as people may not be aware of the artist’s intent, whereas in a gallery or museum there can be more information available, as well as the audience possibly being more open to the artist’s intended message.

In Chernobyl, Yanobe encountered the residents of the restricted-entry zone, known as “Samosely” (secret returnees), and although Yanobe was sometimes welcomed, he was also harshly criticized when they saw him wearing the Atom Suit and thought he was mocking them for being radioactive. Yanobe was also shocked to see that they had brought a three-year-old child to such a dangerous location and he experienced a lot of pain that only reality, not fantasy, can bring. Yanobe regretted that he had hurt the local people with his creation, and after he was freed from the illusion of danger caused by the end of the century, he used these experiences to create his work on the theme of “revival” in the 21st century.

Atom Suit Project: Nursery School 4, Chernobyl (1997) Photo: KIGURE Shinya

In 1996, partly due to the fact that the “Tanking Machine” was experiential, Yanobe was allowed to participate in the “Traffic” exhibition at the CAPC Bordeaux Museum of Contemporary Art, which saw the origin of relational art and relational aesthetics, as advocated by French curator Nicolas Brailleau. Today, Yanobe is not discussed in the context of relational art, but I think it is important to emphasize that Yanobe was not only an adapter of subcultural aesthetics, but he was also working on a new form of art for the next generation.

It’s not a lie to say that the world today is clearly already in a state of crisis. We are in the midst of several crises that threaten the very existence of the human race, including dramatic warming due to climate change, flooding that gets worse every year, earthquakes, and pandemics. It is said that we are in the “Anthropocene” era, in which human beings are drastically changing the geology and the environment of the earth, and art is not immune from these changes. Yanobe’s shift from a world of fiction alone to one that emphasizes the relationship with reality in 1995 has become even more important today.

In the midst of prolonged social isolation, many people may lose their sense of time or suffer from anxiety. However, as stated in the introduction to this exhibition, there is also the example of Isaac Newton, who was able to make numerous historic discoveries by immersing himself in research during a pandemic. An environment created by the isolation of a work such as “Tanking Machine” could be a springboard for rebirth and creation. From Western art to Japanese subculture, sensory deprivation to sensory expansion, and from fiction to reality, Yanobe was a pioneer of the 90’s, and I think we can learn a lot from the path he has forged.

(Translated by Todd Goldman)

This article is reprinted from the August 9, 2021 issue of eTOKI.